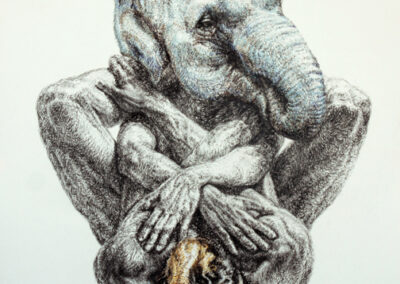

Our latest Artist You Need To Know is someone whose experiences can’t help but manifest in his works, as he was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, before moving to Toronto (2005) and becoming a Canadian citizen in 2011. Ashley Johnson offers the following about his practice: ‘We have to change our way of thinking about objects, space and time to incorporate the insights of quantum mechanics. This means endorsing the ambiguity of something being both particle and wave and acknowledging the role of the observer as creator. Art and culture, including language, are biological expressions projected into society. Every move we make or quality we endorse is inherently defined by our animal possibilities and limitations.’ (from his site, which we strongly suggest you visit, too).

Johnson graduated with a BFA from the University of KwaZulu-Natal and although his training was in traditional disciplines like painting and sculpture, he has expanded into installations that incorporate audio and creating environments, through his works.

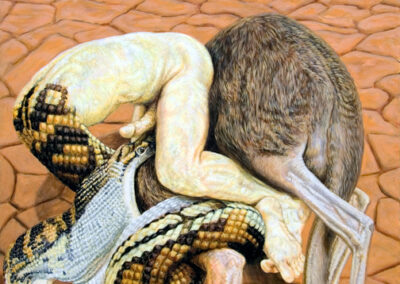

While still in Johannesburg, Johnson co-founded Dasart, an artists’ collective employing socialist art to challenge the assumed ‘positive’ narrative espoused about the connection (or perhaps exploitation) between humanity and the environment. These challenging installations were mounted in various public galleries and museums throughout South Africa: a fine example was Dasart Colonial Mutations which fractured the optimism of the Industrial Revolution with late 20th century concerns about the side effects of this ‘progress’, such as pollution or industrial waste. Works from the gallery’s collection, that averred a colonial, and ‘positive’ narrative, were situated next to works made from industrial leavings, as a direct provocation to the ‘accepted’ history of our use (or abuse) of the environment. Another collaborative work by Dasart, Transmigrations: Rituals & Items, was exhibited across South Africa (Johannesburg Art Gallery, Oliewenhuis Art Museum and the Ann Bryant Art Gallery), and internationally (UABC Tijuana and ASLA, Los Angeles, USA) from 1999 to 2002. This show also included artists (of many ethnically diverse arenas) not just from South Africa, but also from Canada, the U.S. and Mexico, and was nominated for the Cultura Premios Award in Tijuana.

Johnson came to Canada in 2005, but the final significant work he produced in S.A. was Cannibal Communicator: The Congo Holocaust. Like many of his works, it was both evocative aesthetically and spoke of a history that was unsettling, but necessary to bring to light. Cannibal focused upon the ‘history of rubber from when HM Stanley explored the Congo region to the devastation caused by King Leopold II of Belgium’s rapacious exploitation of the resources. The installation was selected for a national competition, the Brett Kebble Award, but unfortunately the patron was assassinated so it was never shown.’ One might argue that this act of violence indicates the volatility of questioning, or defying, dominant social histories, as Johnson’s art, and his work with Dasart, so often did. Writing about a later artwork of his own, Johnson very openly states that ‘my African life was fraught with anxiety and guilt, as one battled to try and make a worthwhile artistic statement in the face of overwhelming indifference.’

Much more of his work, and his considered reflections and writings on his practice, can be found at his site.