Our latest Artist You Need To Know succumbed to leukemia nearly two decades ago, but (to quote gallery director / curator Niamh Coghlan) ‘her work stands out for being so open: she was not ashamed nor scared of showing her body at its most vulnerable, naked and scarred from surgery – the images are incredibly powerful….[it is] work which can often be unsettling in its openness. It’s almost confrontational in it’s openness.”

-

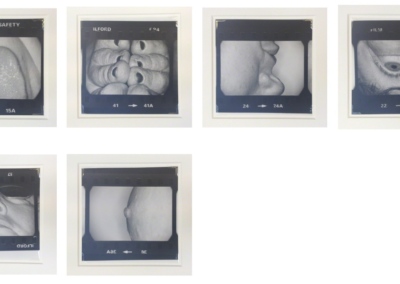

Body Parts, 1978

-

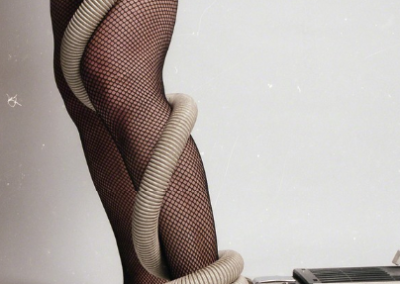

Libido Uprising, 1989

-

Photo Therapy: My Mother as a War Worker

-

Libido Uprising: Beauty Work, 1989

-

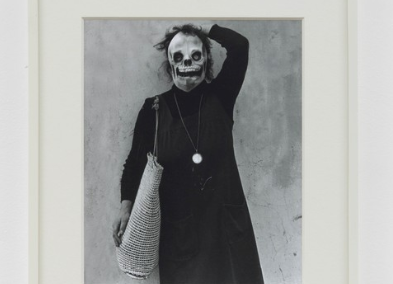

The Bride, 1984-86

-

Revisualisation: Remodelling Photohistory, 1981-1982

Jo Spence (1934 – 1992) was a British photographer, writer, cultural worker, and a photo therapist. Born to a working class family, she came to commercial photography later in her life but soon began her own agency specializing in family and wedding photography, which fed into her later more critical analysis of the assumptions and strictures of these social spaces. In the 1970s, this ‘unintended’ research led her to focus upon documentary photography, adopting a politicized approach to her art form, with socialist and feminist themes. These images could be said to offer documentation of that which her work in the commercial ‘mainstream’ field ignored, or denied, especially in terms of family or social assumptions. Spence, writing in 1979 to accompany her work Beyond the Family Album, Public Images, Private Conventions asserted that she wanted to “question […] who represents who in society, how they do it and for what purpose.”

-

A Picture of Health: Helmet Shot, 1982

-

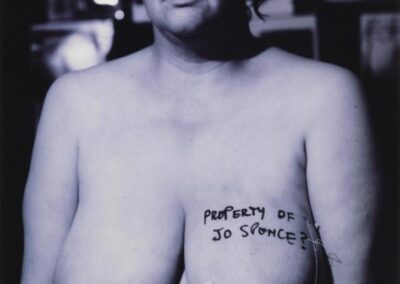

Property of Jo Spence, 1982

-

A Picture of Health : How Do I Begin? 1982-83

-

Photo Therapy : Work on Emotional Eating, 1984

-

Narratives of Dis-ease : Included, 1990

-

The Final Project [Sandwiched Portrait], 1991–1992

Spence is perhaps best known for her self-portraits about her own fight with breast cancer, where she turns the camera around to chronicle her own story, with an equally frank eye. From Skye Skerwin, writing in The Guardian: “This series of self-portraits is both alternative therapy and a critical response to modern medicine, with Spence regaining ownership of her body by documenting her treatment.”

Critic Ashleigh Kane points out that “there are few female photographers as fearless as the late British photographer Jo Spence. A leading feminist and socialist figure in her field, Spence’s work utilized the power of the camera to challenge society on issues of gender, class, mortality, identity, and, perhaps most importantly, her own history.”

Her work can be found in the following collections: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, France Gallery of Modern Art (Glasgow, UK), MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Museo Reina Sofía (Spain), Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi (Poland), New Hall Art Collection at Murray Edwards College Cambridge (UK), Princeton University Art Museum (USA), Ryerson Image Centre (Canada), Tate (UK), Tufts University Art Gallery (USA), Victoria and Albert Museum (UK), and the Wellcome Trust (London, UK). A significant list of her exhibitions, considering her premature passing, can be found here (this gallery is also the keeper of her archive).

-

![The Final Project [Specimen Jars], 1991-92](data:image/png;base64,iVBORw0KGgoAAAANSUhEUgAAAZAAAAEcAQMAAADTA3AsAAAAA1BMVEUAAACnej3aAAAAAXRSTlMAQObYZgAAACVJREFUGBntwYEAAAAAw6D7U0/hANUAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA4BOJQAAZePGUkAAAAASUVORK5CYII=)

The Final Project [Specimen Jars], 1991-92

-

![The Final Project [Small skeleton 1], 1991-92](data:image/png;base64,iVBORw0KGgoAAAANSUhEUgAAAZAAAAEcAQMAAADTA3AsAAAAA1BMVEUAAACnej3aAAAAAXRSTlMAQObYZgAAACVJREFUGBntwYEAAAAAw6D7U0/hANUAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA4BOJQAAZePGUkAAAAASUVORK5CYII=)

The Final Project [Small skeleton 1], 1991-92

-

![The Final Project [Mask 3], 1991-92](data:image/png;base64,iVBORw0KGgoAAAANSUhEUgAAAZAAAAEcAQMAAADTA3AsAAAAA1BMVEUAAACnej3aAAAAAXRSTlMAQObYZgAAACVJREFUGBntwYEAAAAAw6D7U0/hANUAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA4BOJQAAZePGUkAAAAASUVORK5CYII=)

The Final Project [Mask 3], 1991-92

-

The Final Project, 1991

-

Remodelling Photo History:Victimization, 1981-82

-

Remodelling Photohistory: Realization, 1982

To return to the words of Skye Skerwin: “In all of her work, Spence confronted us with the things society tries to conceal – not least women’s unconventional physiques. In The Picture of Health she upped the ante, bringing disease into the frame. In one bare-chested photo, she stands before a mammogram, her breast laid out between its slabs like a separate entity. Later, she poses in a biker’s helmet, holding up her arms to reveal battle scars.”

Spence was also an educator and broadcaster and it isn’t hyperbole to state that without Jo Spence, there would be no Cindy Sherman, Gillian Wearing or even Tracy Emin.

Jo Spence succumbed to leukemia in London in June 1992.

![The Final Project [Specimen Jars], 1991-92](https://artishell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/The-Final-Project-Specimen-Jars-1991-1992-400x284.png)

![The Final Project [Small skeleton 1], 1991-92](https://artishell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/The-Final-Project-Small-skeleton-1-1991-1992-400x284.png)

![The Final Project [Mask 3], 1991-92](https://artishell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/The-Final-Project-Mask-3-1991-1992-400x284.png)