The next Artist You Need To Know is Marion Nicoll (1909 – 1985).

Nicoll is often cited as one of the first abstract painters in the history of art in the province of Alberta. She was a trailblazer in other ways, including becoming the first woman instructor at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art and would be the first female artist from the Canadian Prairies to become a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (in 1977).

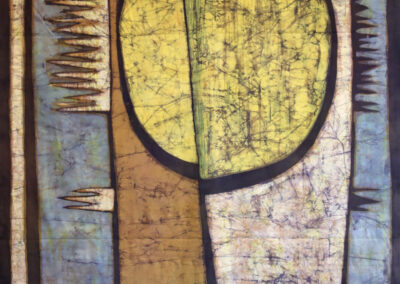

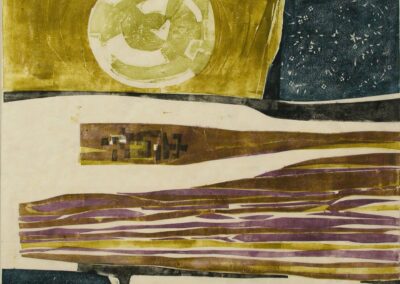

From the Canadian Art Institute | Institut de L’Art Canadien: “Marion Nicoll navigated life as a woman artist to establish her own distinct voice in a male-dominated art world. She began in the later 1920s and 1930s, painting naturalistic scenes while teaching design and craft. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s she became recognized for her batiks and experimented privately with automatism. In 1959 she made the transition to hard-edge abstraction and by the early 1960s emerged as one of Canada’s most important painters.”

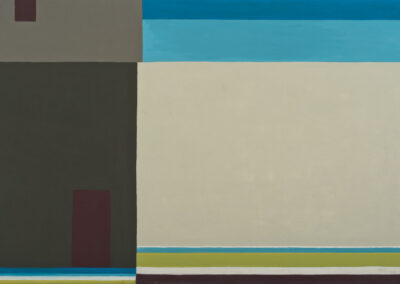

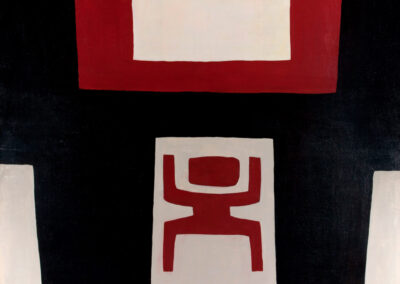

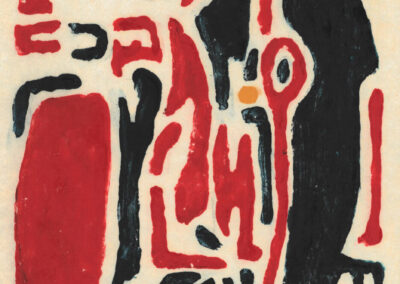

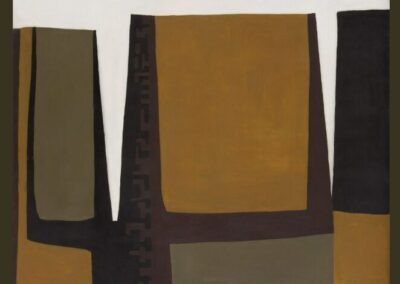

Nicoll, speaking about her work in 1959, asserted that “Colour for me is a shape and a shape is a colour—one demands the other.”

She was born in Calgary, Alberta : her parents were immigrants of Scottish, Irish and French heritage. In high school Nicoll took classes at St. Joseph’s Convent in Red Deer (1925 – 1926). Nicoll attended the Ontario College of Art in Toronto and while there her instructors included a number of artists who were part of the Group of Seven, including Arthur Lismer, J.E.H. MacDonald and Franz Johnston. Upon her return to Calgary, Nicoll’s major influence as a student was A. C. Leighton : she attended ‘the Tech’ – the Provincial Institute of Technology (this institution would birth the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology, as well as the the Alberta College of Art which is now the Alberta University of the Arts in Calgary). Nicoll would be offered a teaching position at the Tech in 1932, shortly after completing her fine arts degree.

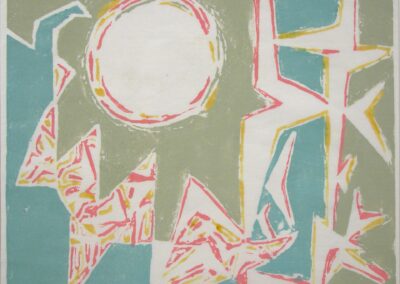

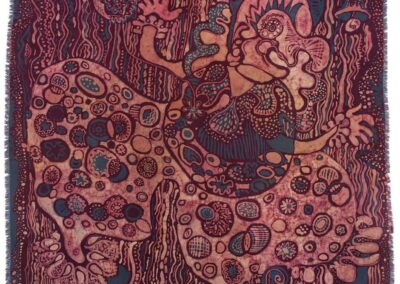

But Nicoll would move to London (in the U.K.) seeking a more diversified and focused arts education, and after studying at the Central School of Arts and Craft (now known as Central Saint Martins) she would return to resume teaching at the Tech in 1938, enhancing the existing program with her new skills in the areas of batik, block printing and screen printing.

In 1940 Nicoll married and left her teaching position : her husband was a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force and his duties (considering that WW II was taking place at this time) required them to be on the move to various places. This tumultuous period would end when they settled in Calgary : Nicoll began teaching at the Banff School of Fine Arts in the summers where she connected with Jock Macdonald. He had just been hired as the head of the Tech’s Art Department and this was surely a factor in Nicoll rejoining the teaching staff there in 1946. MacDonald also influenced Nicoll’s painting style by introducing her to automatism. This art movement was based around the ideology of expressing – or unleashing, through a resistance to predetermining subject matter or composition – the creative force of the unconscious in art.

Nicoll was as important as an educator as an artist. Catherine Mastin (an impressive museum director, curator, writer, and art historian) has asserted that Nicoll had a “pivotal role as an educator in mentoring women.”

Nicoll at first continued her more landscape works, and was reluctant to share her more abstracted paintings. However, she attended the Emma Lake Artists Workshops in 1957, in Saskatchewan, where she was inspired to explore this style further. She left her teaching position – taking a leave of absence – to go to New York City and study with the Art Students League. At this time a number of seminal artists who were redefining painting within the fields of abstraction were working and exhibiting there : when Nicoll returned to Calgary – with some reluctance to leave the creative milieu of NYC – she was a very different artist.

However, abstraction was becoming more respected (both in Calgary, where Nicoll resumed her teaching and across Canada) and she was praised by no less than Clement Greenberg. Nicoll retired from teaching in 1966 to focus upon her artmaking full time. A gallery at the Alberta College of Art and Design is named in her honour.

An extensive listing of her exhibitions and other notable accomplishments can be seen here.

Though she is perhaps best known as a painter and for her strikingly vibrant abstractions, Nicoll also worked in a diverse range of media, including print-making, ceramics, batiks and jewelry making. In 1971, her arthritis forced her to give up painting, but this did not stop her studio practice so much as diversity it, as Nicoll often worked in a technique she called ‘clayprinting’, utilizing her experience in both jewelry making and printmaking.

She was a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, and was recognized with the Alberta Achievement Award of Excellence for Outstanding Contribution to Art in 1984. In 1985, Nicoll would pass away at the age seventy-five from a heart attack.

Nicoll’s artworks can be found in many public and private collections in Canada and internationally. These include the Alberta Foundation for the Arts, the Art Gallery of Alberta, the Glenbow Museum (which holds the majority of her work), the National Gallery of Canada, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The Rooms, the University of Regina and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

Much more about her life, work and legacy can be seen here, as Nicoll was an artist highlighted by the Canadian Art Institute | Institut de L’Art Canadien. From their fine, in depth profile of Nicoll : “Mid-twentieth-century Alberta was a surprising location for a female artist to prosper and build a cultural legacy for generations to come—but that is exactly what Marion Nicoll did. Defying prevailing gender norms and conservative attitudes in Calgary, she ushered in a modernist revolution in Western Canada with her innovative hard-edge abstract paintings. In the process, she became one of this country’s most celebrated pioneers of contemporary art.”