Our next Artist You Need To Know is Hans Bellmer (1902 – 1975).

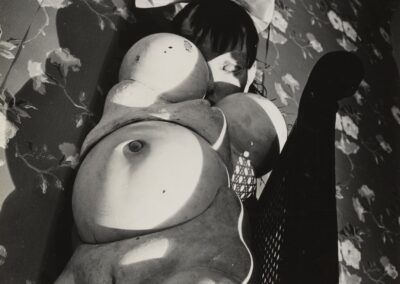

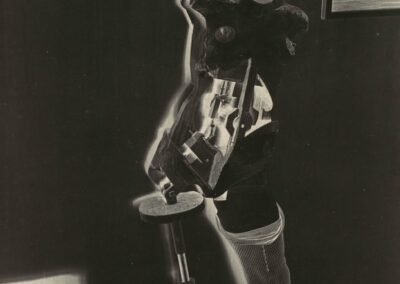

Bellmer was a German artist who would later live in France. He is known for his drawings, etchings and some photographs that illustrated the 1940 edition of Histoire de l’œil by Georges Bataille (one of the most controversial books of the 20th century) but is easily best known for the life-sized female dolls he produced in the mid-1930s that spurred his photographs, sculptures and installations with Die Puppe (The Doll) in their various iterations . Historians of art and photography also consider him a Surrealist photographer.

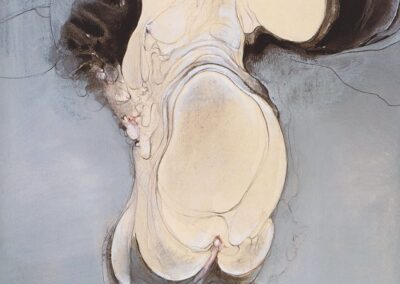

His work is almost immediately recognizable – in both a positive and negative sense, straddling art, erotica and perhaps even pornography – and his aesthetic has influenced a number of artists even nearly a century after some of his most famous works were created.

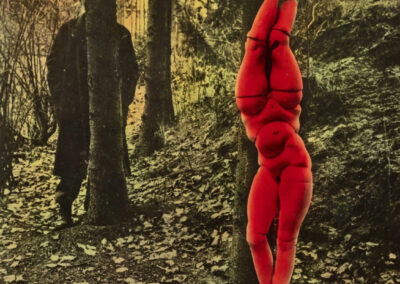

From The Art Story: “Hans Bellmer’s art, often in the form of dolls he called language images, served as a form of personal therapy, in which he objectified abusive relationships, explored his fantasies, and projected the essence of his desire for women and objects. He lived through the repression of artists in Nazi Germany, which became another trauma informing his art. After the war, he became well known for his explicit and sometimes pornographic illustrations. He created images that reflected what he felt was a disturbing, and disturbed world. His work has been hailed by some as representing the limits of human sexuality, while others have found his work to simply objectify the female body as a captive of the male sexual gaze.”

Bellmer asserted that one must “do pretty things while simultaneously scattering the salt of deformation with a hint of vengeance” : conversely writer Alain Jouffroy (a contemporary of Bellmer’s) described the artist’s work as “an orgy of fantasies, projections, substitutions, displacements, even hallucinations.”

Bellmer was born in the city of Kattowitz, then part of the German Empire (now Katowice, Poland). He had a contentious relationship with his father, and this anger and resentment would be with him all his life and inform many of his works. He studied engineering at the Berlin Polytechnic solely to get away from his father, but never truly abandoned his interest in art. Bellmer would quit school in 1924 and began working as an illustrator / designer for the Malik-Verlag publishing house.

But Bellmer was already intensely interested in the burgeoning Dada movement in Germany, and he began to illustrated the works of several of their writers – most notably Das Eisenbahnglück oder der Antifreud by Mynona [Salomo Friedlaender], in 1925. His circle of friends included John Heartfield, Rudolf Schlichter, and George Grosz while also going to various talks, lectures and events at the Bauhaus. This was a unique and vibrant period for art in Germany – and Europe – but it would all be suppressed and attacked by Hitler’s Nazi regime. Bellmer – like his friend Grosz – was targeted and censored by the repressive regime. For Bellmer this was also personal : his father was a repugnantly vocal nazi. In 1933 Bellmer became estranged permanently from his father and “made a vow to refrain from any useful activity (such as working as an illustrator) that might assist the Nazi regime, demonstrating his political conscience.” (from here)

It has also been argued by some art historians that Bellmer indulged more ‘perverse’ aspects of his work specifically to challenge the Nazi government’s policy on ‘degenerate’ art, and that this was also linked to a desire to offend and ‘scandalize’ his father.

During WW II, Bellmer created fake passports to assist the French Resistance : he was captured and held at the Camp des Milles prison at Aix-en-Provence for nine months by the Nazis.

“If my work is found to scandalize, that is because for me the world is scandalous.”

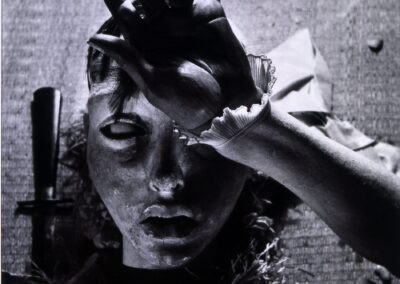

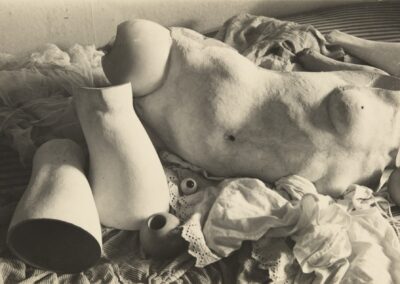

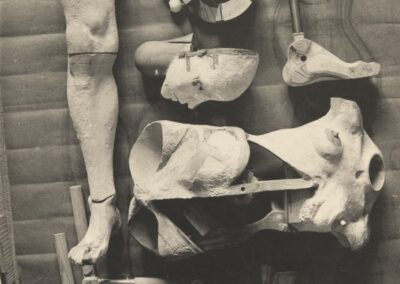

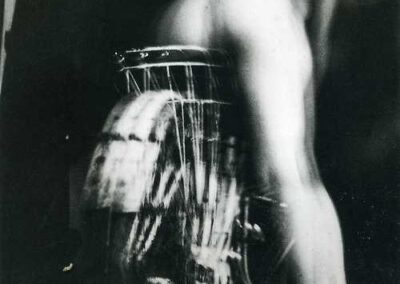

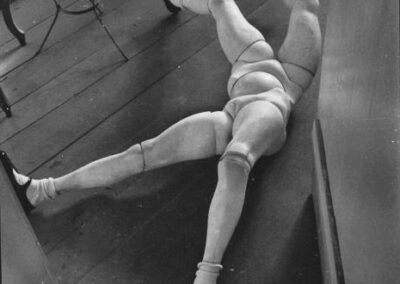

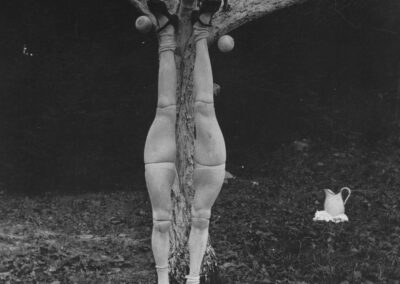

From here : “Hans Bellmer produced the first doll in Berlin in 1933. Long since lost, the assemblage can nevertheless be correctly described thanks to approximately two dozen photographs Bellmer took at the time of its construction. Standing about fifty-six inches tall, the doll consisted of a modeled torso made of flax fiber, glue, and plaster; a mask-like head of the same material with glass eyes and a long, unkempt wig; and a pair of legs made from broomsticks or dowel rods. One of these legs terminated in a wooden, club-like foot; the other was encased in a more naturalistic plaster shell, jointed at the knee and ankle. As the project progressed, Bellmer made a second set of hallow plaster legs, with wooden ball joints for the doll’s hips and knees. There were no arms to the first sculpture, but Bellmer did fashion or find a single wooden hand, which appears among the assortment of doll parts the artist documented in an untitled photograph of 1934, as well as in several photographs of later work.”

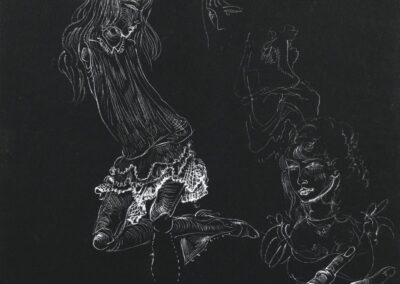

Post WW II, Bellmer would spend the rest of his life living and working in Paris. He progressed from his doll making to working solely in two dimensional media “creating erotic drawings, etchings, sexually explicit photographs, paintings, and prints.” In 1954, he met the German writer and artist Unica Zürn, who became his companion [and collaborator on many occasions]. Their relationship was tumultuous, due to both’s physical and mental health issues : when Bellmer suffered a stroke in 1969 his professed inability to care for Zürn : she would commit suicide in 1970.

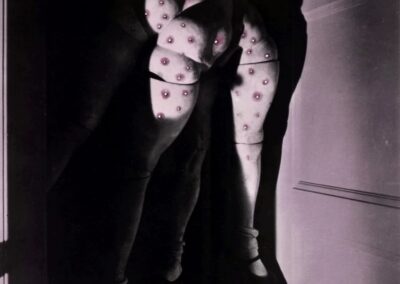

He continued working into the 1960s. Of his own work, Bellmer said, “What is at stake here is a totally new unity of form, meaning and feeling: language-images that cannot simply be thought up or written up … They constitute new, multifaceted objects, resembling polyplanes made of mirrors … As if the illogical was relaxation, as if laughter was permitted while thinking, as if error was a way and chance, a proof of eternity.” (from here)

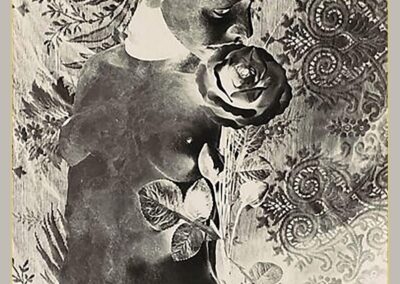

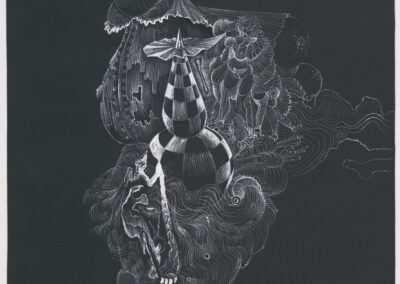

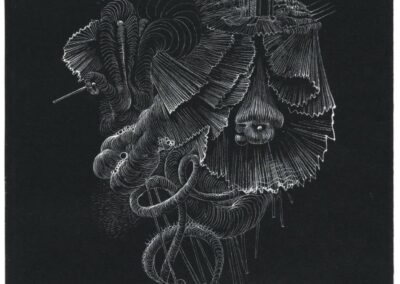

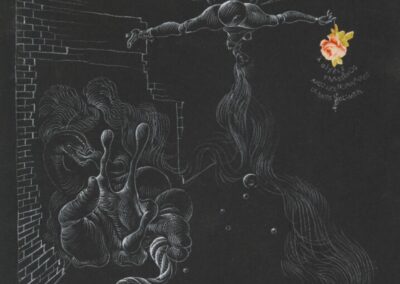

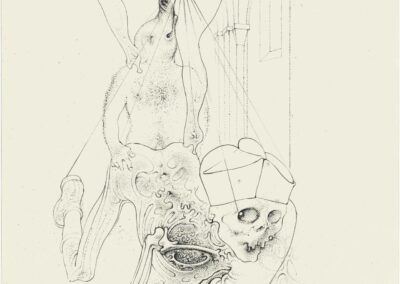

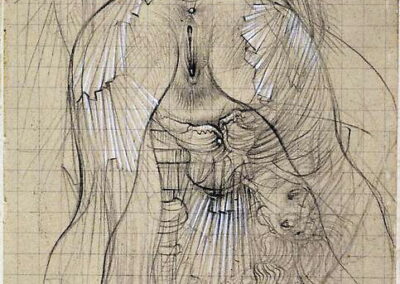

The images below are a selection from Bellmer’s illustrations for Bataille’s Story of the Eye and several other illustrative collections.

“The body is like a sentence that invites us to rearrange it, so that its real meaning becomes clear through a series of endless anagrams.”

Hans Bellmer died from cancer in 1975 : he had arranged that he would buried alongside Unica Zürn at Père Lachaise Cemetery with a tomb marked Bellmer – Zürn.

As stated Bellmer’s work is contentious, both in creation and interpretation – but this has only made his influence even more pervasive, in a variety of spaces outside of the visual arts but in larger cultural and political spheres and with many artists responding to Bellmer’s legacy with admiring and critical eyes….”Bellmer remains one of the most influential and notorious artists of the 20th century. As his creations, and his possible intentions behind them have been reinterpreted and debated, his reputation and impact have grown. The feminist movement in particular took a dim view of his objectification of women, as Rudolf Uenzli points out in Surrealism and Misogyny, “these are not just “bodies;” these are always female figures.” Subsequently Bellmer’s imagery was co-opted and used by the 1990s Riot Girl movement, most iconically by Courtney Love in her disturbing child/woman “Kinderwhore” aesthetic. His work was a strong and acknowledged influence on the erotic art of Paul Wunderlich and the creations of Louise Bourgeois, such as Filette (1968). Bellmer’s doll theme is perhaps most clearly elaborated by Cindy Sherman‘s many doll pieces, some of which explicitly reference Bellmer such as her Untitled #261 (1991) of a decapitated head, amputated legs, and detachable breasts and her Untitled #263 (1991) – a fusion of male and female at the torso, recalling his Cephalopod. His contentious evocations of childhood sexuality have been elaborated by Jake and Dinos Chapman in works such as Zygotic Acceleration (1995). The highly stylized yet disturbing “human Barbie” studies of Alex Sandwell Kliszynski use modern tools to take Bellmer’s fantasy to a new level, turning human flesh into a plastic anagram.” (from here)

More information about Bellmer’s life and work can be seen here at The Art Story and many more of his two dimensional works can be seen here.