The next Artist You Need To Know is Honoré Daumier (1808 – 1879).

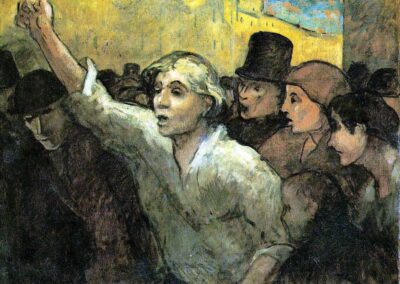

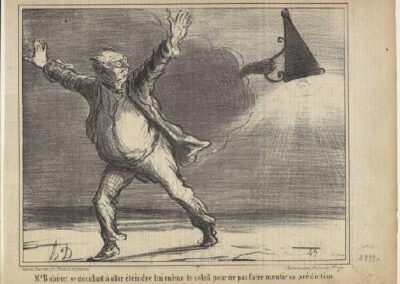

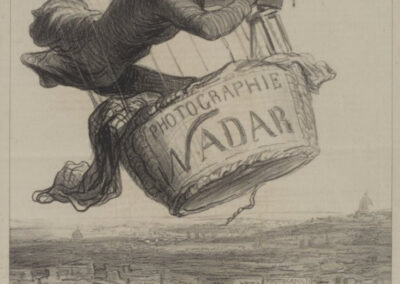

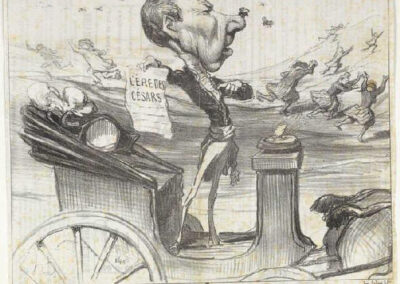

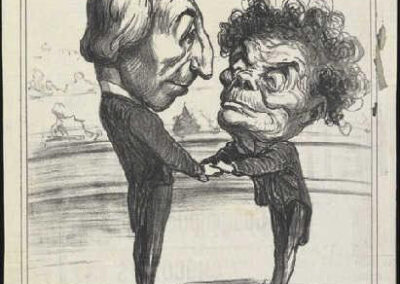

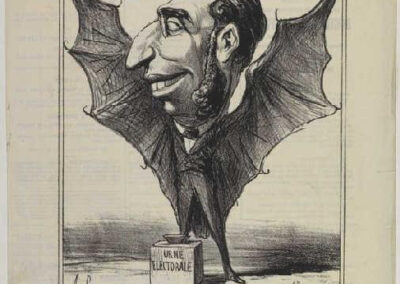

Honoré – Victorin Daumier was a French artist who worked in painting and sculpture : but his true legacy was in printmaking and his artworks in that field were essential to the development of political cartoons (even more than a century after his death). Daumier’s prints were an essential part of the political landscape and conversation in France from the turbulent and significant period of the Revolution of 1830 to the fall of the Second French Empire in 1870. His caricatures and cartoons were a mainstay of publications like La Caricature and Le Charivari : Daumier was famous for his insightful and often barbed political observations and many of his images are immediately recognizable even today.

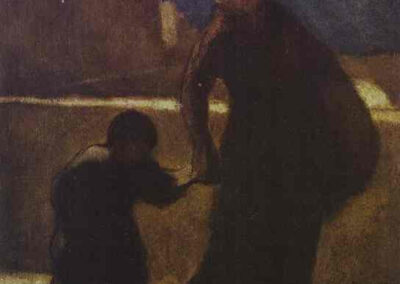

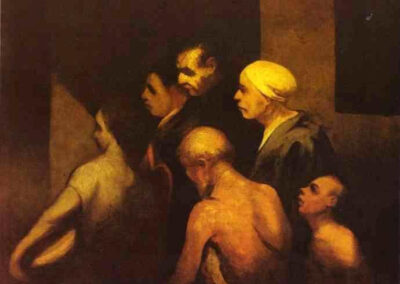

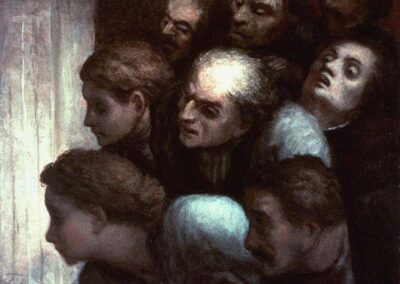

A further testament to Daumier’s importance is that his paintings – nowhere nearly as well known during his own lifetime as after – were often cited by many of the artists who would develop and proliferate Impressionism as well as several other art movements that branched out from there.

“One must be of one’s own time.” This is an appropriate quote from Daumier as his work cannot be separated from the hectic and shifting political times within which he lived.

Daumier was born in the South of France in the port city of Marseille but lived the majority of his life in Paris. He showed interest and promise at a young age in the arts, though his father tried to discourage this and direct him to more practical areas. At 14, he began having lessons with artist and antiquarian, Alexandre Lenoir. He took classes at the Académie Suisse (beginning in 1823) which catered specifically to art students of lesser means. Daumier’s fellow students at this school reads like a primer on the significant French artists of the next generation, including Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, and Paul Cézanne.

Concurrently Daumier was working for the publisher and lithographer Zepherin Belliard : it was here that Daumier was introduced to the printmaking method known as lithography and began experimenting with this revolutionary – pun intended, considering the arc of his career and times, and how to speak of his work is to speak of the history of his nation and Europe – medium.

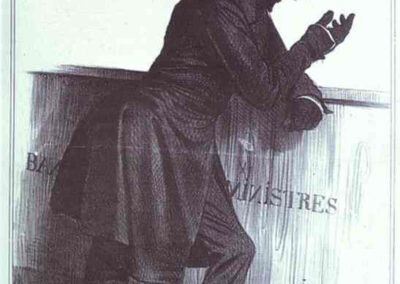

Daumier’s work in lithography is what he was most renowned for : the ability to quickly produce and disseminate images in papers, periodicals and other matter for mass consumption allowed his work to blossom, and his audience to be as wide as possible at that time. When he was only 21, his political caricatures were well known : this coincided with the 1830 revolution in France which led to relaxation of some censorship laws and a wider range of dissenting political opinions in the popular press, of which Daumier’s cartoons were an essential element.

From here : “Two political satirists working in the 1830s were examples for the budding young caricaturist. Hippolyte Bellangé and J.J. Grandville produced dramatic lithographs documenting the rebellion of July 1830, three bloody days of rioting, when Paris rose up against the repressive regime of Charles X. The early years of Daumier’s entry into the world of political satirical imagery provided him and other artists with abundant subject matter as the rule of Charles X’s predecessor, Louis Philippe I, the so-called “Citizen King,” were no less tumultuous before a subsequent revolution erupted in 1848.”

His words : “Freedom and justice for all are infinitely more to be desired than pedestals for a few.”

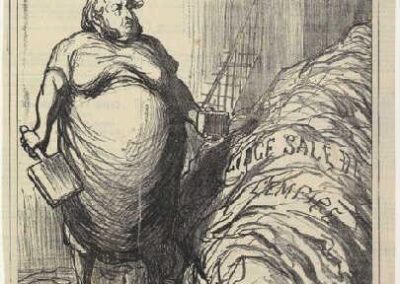

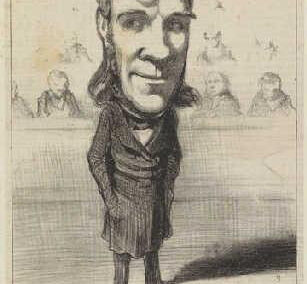

Daumier was also inspired by a colleague – sculptor Auguste Préault – to create three dimensional iterations of his “increasingly more brutal and biting political caricatures. He began producing small portrait busts of politicians in clay, basing them on sketches he made while attending parliamentary sessions. He frequently created two-dimensional, lithographic versions of the figurines, all of which were satirical verging on viciously truthful – likenesses that said as much about the interior workings of the subject as his physical appearance, although the latter was consistently strikingly accurate. His caricatures of 1834 collectively formed a controversial series he titled Le Ventre législatif (The Legislative Belly), a kind of cynical group portrait of the members of the National Assembly that was published in the journal, La Caricature, that same year. He followed it shortly after with a sequel far more sinister, Rue Transnonain, which documented the bloody aftermath of a police raid. Daumier had found his media and his artistic voice and it was both graphic and politically powerful.” (from here. More information about the specific pieces mentioned in this paragraph can also be seen there.)

During this period, his artworks were considered social critique on a par with the writing of his contemporary Honoré de Balzac (1799 – 850), which were unflinching in their criticism of social ‘standards’ and the status quo in Paris and the larger French social sphere. Balzac was a French novelist and playwright whose writings – especially La Comédie humaine – still resonate today.

At this time, Daumier’s artistic circle included such notables as Eugène Delacroix and Jean-François Millet.

Interestingly, considering the proliferation of Daumier’s artwork, there is a scarcity of information – especially primary documents, such as letters or journals – about his own life and this has limited attempts to offer more extensive biographies of the artist. Alternately, some art historians argue that his biography is his artwork and offer us all we truly need to know about him.

Daumier’s career was often defined not just by his immediate world but by shifting cycles of a free press and then attempts to assert strictures of censorship on artistic and political commentary. This meant that Daumier – like many writers and artists of his epoch – were often in danger of prison or murder for what they produced. His career experienced a number of highs and lows because of this, as often the shifting vagaries of the state – from Republic to Emperor to the class conflict of the times – directly impacted his own ability to make work, or even survive, in those volatile times.

In 1864, Daumier’s importance as a contemporary artist and political voice was well established, and he was once again working for Le Charivari : but his eyesight had begun to degrade and (perhaps tired of the turmoil of Paris) he began to spend more time in rural Valmondois which would eventually become his primary residence – or refuge, if you will. The French government wanted to award him the cross of the Legion of Honour in 1870 (but in a more quiet manner, perhaps to avoid officially recognizing such a prolific critic openly). Daumier was uninterested and declined.

As the Franco – Prussian War (1870 – 1871) raged with a harsh siege of Paris by the Prussian Army, Daumier found inspiration in the chaos around him and created some of his finest lithographic works (and some of the finest works in the history of that medium). But this was also the final body of work that Daumier created in that media, so it was in many ways an appropriate swan song to his career.

In 1879, Daumier died after a major stroke at his house in Valmondois. He left many unfinished works, primarily in terms of his paintings : a revival in interest in Daumier’s artworks in the early 20th century led to a greed driven attempt to ‘finish’ or ‘restore’ some of these works, that were often passed off as genuine works but were more forgery than anything else.

This has led to major issues in terms of art historians establishing proper provenance and the authenticity of many works : and has, perhaps, contributed to why his printed works, which existed with a ‘real life’ in his own time, in terms of both political commentary and social realism, are often considered the mainstay of Daumier’s legacy. More about this issue – and a listing of verified works by the artist – can be explored at The Daumier Register.

From here : “The witty caricatures of Honoré Daumier made him one of the most widely recognized social and political commentators of his day and even landed him in jail for insulting the reigning monarch. Daumier’s caricatures stand out as his most successful works, yet he remains unrecognized for the impressive diversity of his art as he produced not only the lithographs for which he is famous but also drawings, oil and watercolor paintings, and sculpture. Daumier pioneered a style of Realism that focused on people of all echelons of society and spared few, with the exception of the working class and the poor, from his sharp wit and scrutinizing eye. He lived in Paris during a period of political and social unrest, which included two revolutions as well as frequent regime changes, a war, and a siege. Many of his works confronted the complex social, political, and economic consequences of the turmoil. Perhaps his greatest contribution to modern art was his ability to capture even the simplest moments in life and infuse them with emotion.”

Many of Daumier’s political works bring to mind the works of a previously featured Artist You Need To Know Käthe Kollwitz : both had an eye that was alternately empathetic and acerbic in depicting the worlds they lived within and the injustices they recorded.

Much more about Daumier’s art and legacy can be seen here at The Art Story, but a more in depth and expansive site titled The World of Honoré Daumier can be enjoyed here.