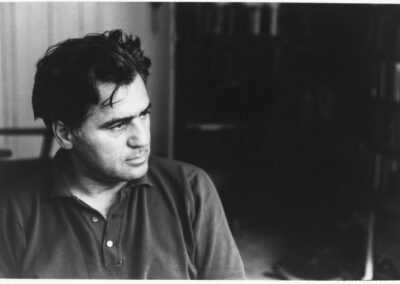

Our next Artist You Need To Know is someone who might be called a social historian with his camera, whose works serve as touchstones for landmarks both in Canada and the world: sometimes this is embodied through the individuals he photographed, but also through his work as a photojournalist.

Sam Tata (September 30, 1911 – July 3, 2005) was a Montreal photographer, and his impressive resume of photo journalism includes TIME Magazine and National Geographic Magazine. He was born in Shanghai, which would also be the place where he took some of his most relevant and evocative images.

-

A crowd parading the portraits of Zhu De, Mao Zedong, Joseph Stalin and Vladimir Lenin, from Shanghai: 1949 The End of an Era, 1949.

-

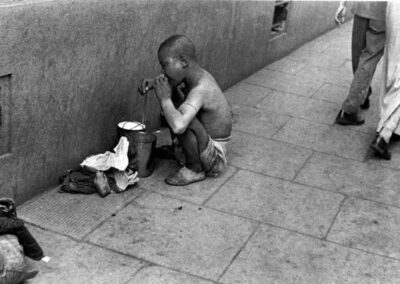

Child beggar, from Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era, 1949

-

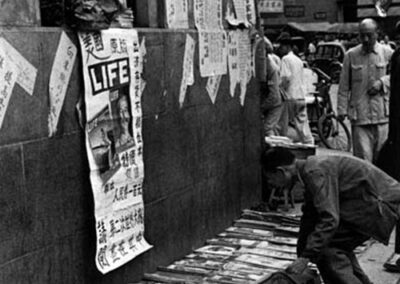

Selling Magazines, from Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era, 1949

Tata was greatly influenced by the famous photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, whom he met in Bombay in 1948. Cartier-Bresson’s genius is evident in Tata’s work, as the former “advised the young photographer to always integrate the environment with people in his photos. The two remained life-long friends. In 1949, Tata photographed events before and after the liberation of Shanghai by the Communists, which led to the establishment of Mao Tse-Tung’s government in China. These documentary photographs of the arrival of Maoist troops and political commissars in that once remarkable city formed the basis of a book Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era published by Batsford Books in 1989.” (From Virtual Shanghai, which also has a fine interview with Tata)

-

At Shanghai North Railway Station, from Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era, 1949

-

Catholic Nuns Boarding on a Ship, from Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era, 1949

-

Cages with song birds, from Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era, 1949

Tata, rather humbly, asserted the following: “I am not a historian with a camera; merely an observer, and as such was fortunate enough to record fragments of a world shaking event, and great historical change. But perhaps best of all, these records recall to me, with much nostalgia, the streets and alleys of a city I loved, its sights, its sounds and smells, and its memories.” (From The Tata Era, a retrospective exhibition by the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography with accompanying catalogue, published in 1988)

-

People's Liberation Army marching in Liberation Parade in Nanking Road, July, from Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era, 1949

-

Communist activists tried by a nationalist military judge, from Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era, 1949

-

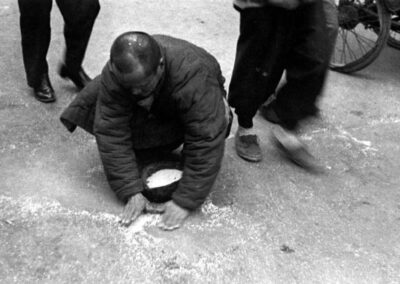

A poor man picking up spilled rice in the street, from Shanghai: 1949 The End of an Era, 1949

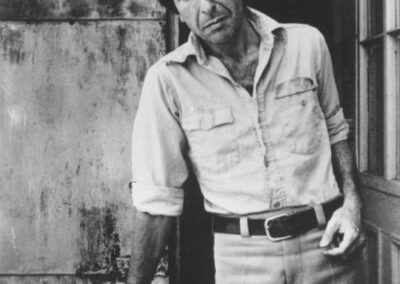

This is but one aspect of Tata’s work: his portraits of Canadians, both accomplished cultural figures and Canadians less well known display a sensitivity to his subjects that have made his portraits iconic. Tata : ‘Actually what you’re doing is bringing out the subject’s reaction to you. So it means that you have to spend some time. While you’re sizing them up they’re sizing you up. I will sit and talk with them for a while. They gradually become more quiet and accepting.’ One of his photographs that is a great example of his fine eye to people existing in moments of history and social change was made into a permanent domestic stamp by Canada Post on April 8, 2015. Tata’s Angels, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, was taken in 1962, at a time when the Quiet Revolution was just beginning; a decade later would see the FLQ crisis, and now, half a century later, that holiday and its significance can be ‘seen’ in this stamp, just as Tata’s Shanghai series also encapsulates historical moments of change and challenge in black and white.

Coming to Canada in 1936, Tata became known as one of the country’s most accomplished postwar photographers and produced a remarkable body of work on India, Japan, Canada and for over 60 years. His book A Certain Identity; 50 Portraits is a study of not just individuals but of Canadian cultural diversity.