Our next Artist You Need To Know is Françoise Gilot (b. 1921).

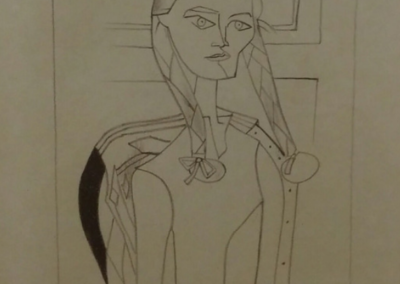

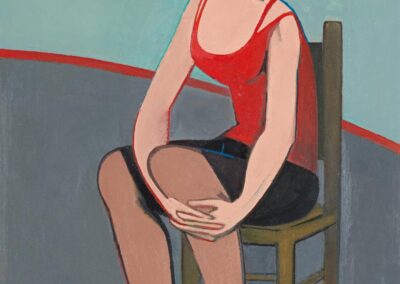

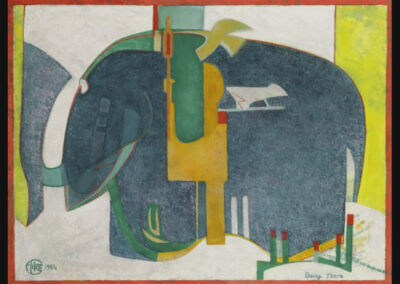

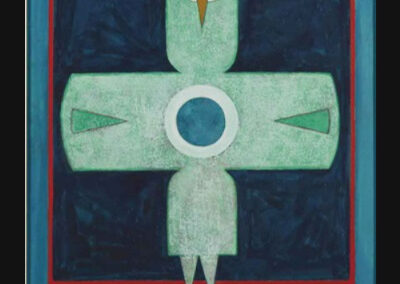

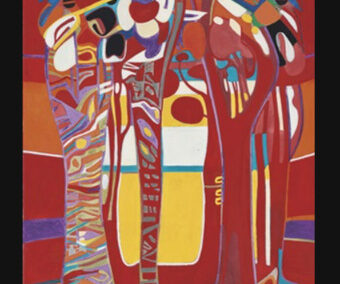

“I must cancel the emptiness of the canvas like an opening gambit in a game of chess,” Françoise Gilot once declared. She was a member of the School of Paris in the 1940s, and “has been pursuing a bold, Modernist vision in her paintings and prints ever since.” She was often at the centre of the “Modernist movement, within which she developed a vibrant career. Ranging from representational and narrative to entirely abstract, her compositions evince influences from Cubism and Fauvism. Gilot focuses equally on the structure of her compositions and the visual and emotional resonance of color as she does on the subjects animating them, including her family and memories, mythology, and the forces of nature, time, and space.” (from here)

Gilot was born in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France: originally left handed, Gilot’s father forced her to switch hands but she became ambidextrous as a result. From an early age she decided she wanted to be a painter, and was initially taught by her mother and later by her mother’s art teacher, a Mademoiselle Meuge, for six years. At the age of fourteen, she was introduced to ceramics, and a year later, she studied with the Post-Impressionist painter Jacques Beurdeley. She obtained a B.A. in Philosophy from the Sorbonne (1938) and a degree in English from Cambridge in 1939, but visual arts was always her true focus, often neglecting her formal studies to visit museums and become part of the larger artistic milieu of her city.

During WWII, Giltot’s father was afraid that Paris would be bombed and sent her to Rennes, France, to begin law school. Sadly, during WWII, many of Gilot’s early works in watercolour and drawing were lost when her father attempted to save many of the family’s belonging by moving them was stymied by a German bomb destroying the truck they were in.

At the age of 19, she abandoned her studies in law to focus upon art, and was mentored by the artist Endre Rozsda. After a back and forth, leaving her law studies several times and at the urging of her father, Gilot passed her written exams (but failed her oral ones) in 1942.

In 1943, she exhibited her paintings for the first time in Paris.

At the age of 21, she met Pablo Picasso. Sadly, Françoise Gilot’s work and life – and her own significant accomplishments – have only recently been recognized, leaving behind how she is “best known for her relationship with Pablo Picasso, with whom she had two children. Gilot was already launched as an accomplished artist, notably in watercolours and ceramics, but her professional career was eclipsed by her social celebrity, and when she split from Picasso, he discouraged galleries from buying her work, as well as unsuccessfully trying to block her memoir [written with art critic Carlton Lake), Life with Picasso.” (from here) It is notable that all the profits from the book were used to help Gilot’s two children with Picasso, Claude and Paloma, in their court battles to be recognized as Picasso’s legal heirs. Considered by some to be one of Picasso’s most significant ‘muses’, Gilot was treated just as shabbily by him as when he dismissed Dora Maar for the much younger Gilot, and there are allegations of both physical and emotional abuse inflicted on Gilot during their relationship.

Most art historians are in agreement that her career suffered a degree of atrophy during their time together.

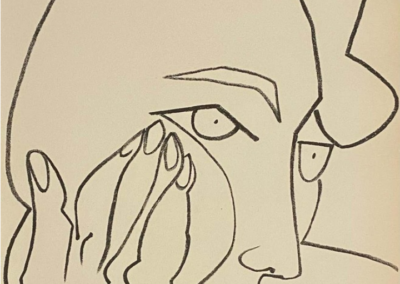

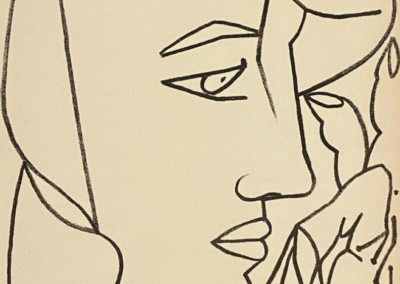

It’s undeniable that Picasso influenced Françoise Gilot’s work – especially when she was experimenting with cubism – but she had her own aesthetic and style, often avoiding “the sharp edges and angular forms that Picasso sometimes used. Instead, she used organic figures.” (from here)

Thankfully, this has changed in recent decades. Her work is on view at – and in the collections of – a number of important venues, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), McMullen Museum of Art (Boston, MA), New Orleans Museum of Art (LA), Muskegon Museum of Art (Michigan), Musee d’Art Moderne (Paris), Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art (Collegeville, PA), National Acadamy of Design (NYC), Musee de Tel Aviv (Tel Aviv, Israel), Women’s Museum (Washington, D.C.), Bibliotheque Nationale (Paris), El Paso Museum of Art (TX), Phoenix Art Museum (AZ), Jacksonville Art Museum (FLA), Museum of the University of New Mexico (NM), University Art Museum, California State University (CA), many United States Foreign Embassies and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Gilot has also produced a number of books, sometimes in collaboration with others. These include: Françoise Gilot — Works 1984 — 2010 , (2011, with Aurelia Engel), Dans L’Arene avec Picasso, (2004, with Annie Maillis), Françoise Gilot Monograph 1940-2000, (2000, with Mel Yoakum, Ph.D.), An Artist’s Journey (1987), Interface: The Painter and the Mask (1983), The Fugitive Eye (poems and drawings, 1976), Le Regard et son Masque (1975), and the aforementioned Life With Picasso, (1964, with Carlton Lake). She also illustrated a number of books, both in the 1950s and the 1980s.

Not solely a painter, in the 1980s and 1990s Gilot designed costumes, stage sets, and masks for productions at the Guggenheim, as well. Gilot was art director of the scholarly journal Virginia Woolf Quarterly from 1973 to 1977, and in 1976, she joined the board of the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Southern California, where she was a teacher until 1983.

She has garnered a number of awards, including a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (1990) and is an Officer of the Légion d’honneur, the French government’s highest honour the arts (2010).

Gilot splits her time between New York and Paris, working on behalf of the Salk Institute (Gilot and polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk were married in 1970 and were together until Salk’s death in 1995), and – despite recently marking her centenary, being 101 years old – is continuing to make work and exhibit internationally. A more complete listing of her many exhibitions can be seen here.

“If I start a painting from a quasi-embryonic state with forms that I make visible to better exclude them later, I do it mostly to initiate a trajectory. Like the ancient Greek philosophers, I want to prove movement by walking. I feel a kind of vertigo in front of the emptiness of a white canvas, and am ready to do anything to fill its void. But fortunately after my first thrust of energy, a hidden voice within me says, “No, that’s not it at all,” and propels me to make alterations that, even if not valid in their entirety, open the way to more reflections and more imaginative propositions. There is a progression; more and more fragments come into focus and begin to be attuned to one another until the whole purpose clarifies itself and, in an instant of enlightenment, leads to cohesion and unity.” (from here)

A site dedicated to her life and work can be seen here.