Our next person of note in our continuing Artist You Need To Know series is Alan Jarvis (1915 – 1972).

Similar to when we featured Norman McLaren, Jarvis is important for his legacy of fostering spaces and communities that were – and still are – essential to the promotion and proliferation of arts and culture in Canada. Jarvis was (in the words of Dr. Sarah Stanners, a contemporary art historian and curator) “a voice that aimed to educate and persuade…he was a Rhodes Scholar…a factory manager, a film industry man, and the first director of the National Gallery of Canada who could call himself an artist.”

When he passed away, several of his obituaries described him as ‘the civil servant who brought art down to earth.’ Sadly, Alan Jarvis’ name and impact is unknown to many Canadians – but “to others he is singularly responsible for making art more popular across the country in the mid-20th century.” (from here)

An accomplished author, editor, and artist, Alan Jarvis attended the University of Toronto (BA, 1938) and Oxford (as a Rhodes scholar, 1938-39). He also was awarded a scholarship to the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University.

Returning to England in 1941, he became a consultant in the Ministry of Aircraft Production. After WWII, he held a number of appointments there, including Director of Public Relations, UK Council of Industrial Design (1945-47); Director, Pilgrim Pictures (1947-50); Head, Oxford House (1950-55); Chairman, London’s Group Theatre; and Director, British Handcraft Export Corporation.

In the summer of 1957, CBC television broadcast a thirteen-part series called The Things We See that Jarvis hosted. The half hour episodes “encouraged viewers to examine ordinary objects for certain patterns, featuring items from the National Gallery. The series was named for Jarvis’ 1947 book The Things We See – Indoors and Out.” (from here) This novel use of the nascent medium of television was groundbreaking both in its form and function, offering ideas and artworks to people in a manner that was impossible even a few years before the CBC broadcasts.

A testament to the impact of The Things We See is that the late Dennis Reid – one of the most impactful art historians and curators in Canada – “watched Jarvis on television in the 1960s [and] Reid’s life would never be the same. “I was greatly influenced by his television program,” said Reid. “I had wanted to be an archaeologist.” But he turned his attention to art. The show….was not only life-changing for Reid but also immensely popular with Canadians at the time.” (from here)

“The role of the artist is not so much to uplift us,” Jarvis said in the final episode, “as to give us the joy of seeing our world with fresh eyes. Learning to see the way artists see does really give one an enormous amount of fun.”

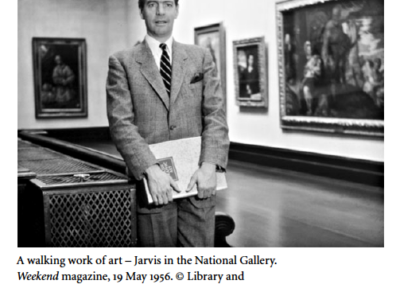

In 1955, Jarvis accepted the position of director at the National Gallery, Ottawa : he was 39 years old. He visited many Canadian galleries, stressing the collection of 20th-century painting and sculpture and encouraging regional art.

He was director of the National Gallery of Canada from 1955 to 1959 : “as head of the National Gallery, Jarvis was a provocative public educator, advocating his idea of “a museum without walls” in countless public appearances. Instrumental in bringing modern art to the National Gallery, he shook artists and the art-minded public out of a period of national complacency.” (from here)

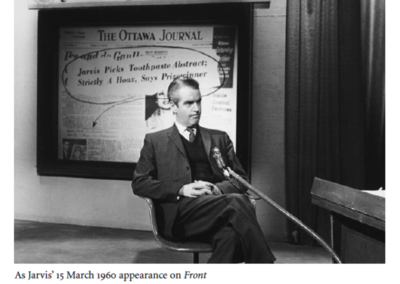

After a “purchasing disagreement concerning European masters”, he was asked to resign in 1959. His resignation – what many still consider his being fired – is too often the sole aspect of Jarvis’ life and history that many know.

Joan Roberts, writing for Quill & Quire, offers the following regarding this incident in a review of Andrew Horrall’s 2009 biography of Jarvis : “His appointment as director of the National Gallery in 1955 made him one of Canada’s most recognizable cultural personalities, but he was fired before his five-year contract was up, his effortless charm having led to careless badinage that got him into trouble. What’s more, as Horrall points out, “the exigencies of running a government department had smacked up against the insouciant emotional shell that prevented him from asking for help and support when he most needed it.” More obviously, he was sandbagged by John Diefenbaker and some of the gravy-stained government yahoos who were furious over major purchases of Renaissance masterworks (not to mention contemporary non-figurative art).”

One might consider the removal of Jarvis, when contemplating Diefenbaker’s legacy, to be as ignorant an endeavour as Diefenbaker’s folly regarding the Avro Arrow….

Jarvis was also chairman of the Society of Art Publications in Ottawa.

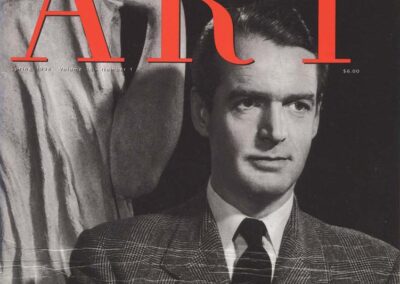

In 1961, Jarvis helped found the Canadian Conference of the Arts in Toronto and was their first National Director. He was essential to the organization of Rothman’s Arts Program in the same decade. Jarvis edited, and wrote articles for several magazines : he was also the editor of Canadian Art Magazine (which would change its name to Artscanada during his tenure there). He organized three exhibitions at the Rothman’s Gallery for the Stratford Shakespearean Festival (1963 to 1965) and was heavily involved in national preparations for Expo 67 in 1967.

His books include the aforementioned The Things We See (1946), David Brown Milne, 1882-1953 (1955), Frances Loring, Florence Wyle (1969) and Douglas Duncan, A Memorial Portrait (1974).

Jarvis was one of several essential voices that wanted to expand what galleries and public institutions considered worthy artworks – with an eye to accessibility and dissemination of visual art to all. Jarvis also was instrumental in helping to change the idea – that would still be rife in many institutions into the 1970s – that Canadian visual arts was not of a calibre and quality to merit the same support and attention as art historical or international art and artists.

For the last ten years of his life, Jarvis free-lanced as a writer, sculptor and art consultant. Jarvis was also the inspiration for a character in Robertson Davies’ Cornish Trilogy : the tragic Alwynn Ross in What’s Bred In The Bone.

In 2009, Andrew Horrall published Bringing Art to Life: A Biography of Alan Jarvis with McGill-Queen’s University Press, which has become a necessary touchstone in Canadian art history. Writing in The Globe and Mail, James Adams states that “Horrall’s 10 years-plus of work is both a portrait of a truly fascinating, almost un-Canadian Canadian and a measure of the great distance the country’s culture sector has travelled.” A number of the images of Jarvis we’re sharing in this post are from that book.

Horrall chronicles the last part of Alan Jarvis’ life as follows (to employ Joan Roberts words again) : “Jarvis, he writes, at first “appeared confident, witty, and happy, though long-time friends saw a diminishing reflection of what he had been in his prime.” Before turning 50, he already “had systematically deceived or disappointed everyone who had extended their hand to help.” He died at 57 in 1972, a slow suicide by alcohol.”

But Dennis Reid’s assessment, in ending, is less dour and speaks more to the foundation that Jarvis laid in his life and work : “I think his greatest contribution was his concept of outreach – the importance of getting out there and touching people who might not otherwise think of going to an art gallery and looking at art. His television programs were pioneering in Canada. For me it was the first time I had heard anyone talk about art in a serious way.”