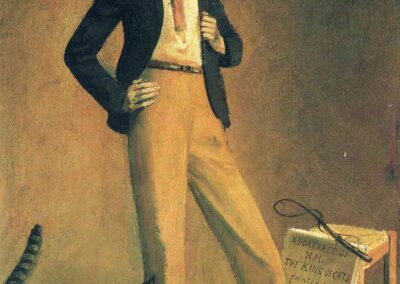

The next Artist You Need To Know is Balthasar Klossowski de Rola who was better known as Balthus (1908 – 2001).

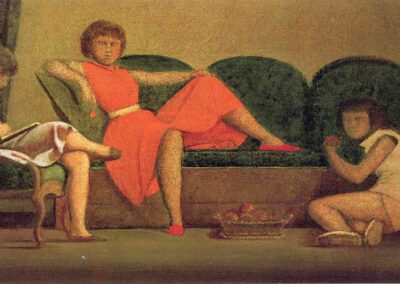

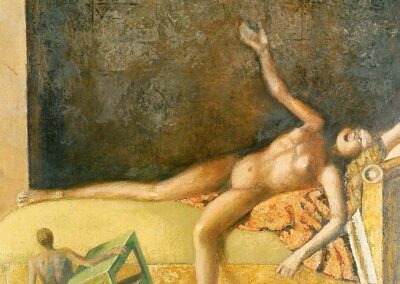

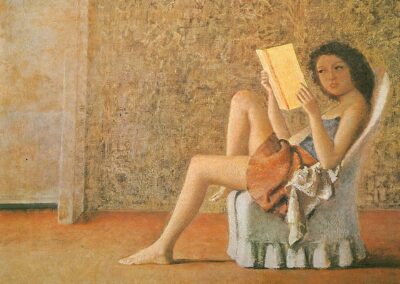

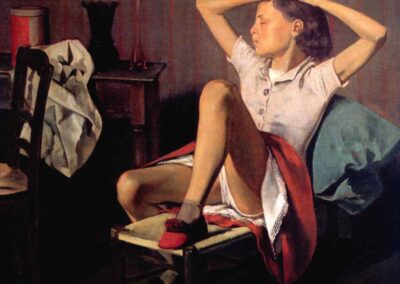

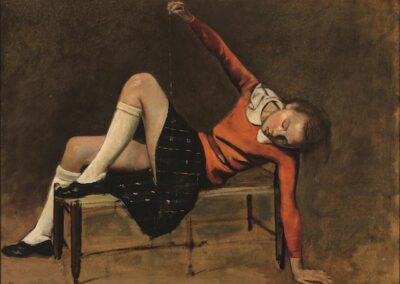

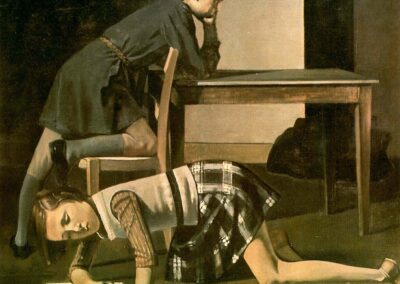

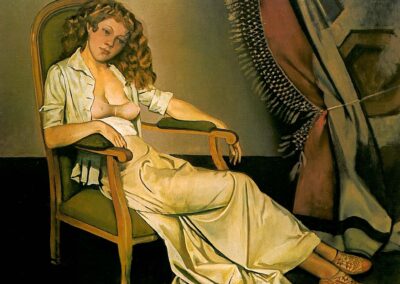

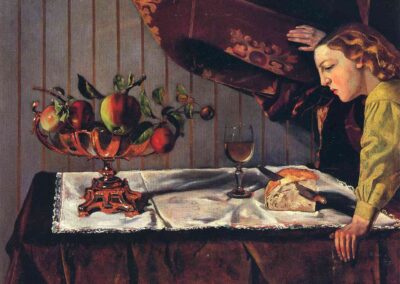

Balthus was a Polish-French painter whose works often had an uncomfortable, erotic element but also a dreamlike atmosphere and imagery. He was reticent to speak about his works and actively resisted any interpretation of his artworks that were not a direct experience of the paintings themselves. His scenes are often populated with “pensive adolescents who dream or read in rooms that are closed to the outside world.” (from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s text for the exhibition Balthus: Cats and Girls—Paintings and Provocations)

Balthus eschewed stylistic categorization and often tried to prevent any biographical narratives defining his work, in a ‘secretive’ manner.

From here : “Balthus’s life and career were as enigmatic as his artworks. Born in 1908, he was a self-taught artist whose work was celebrated for its technical mastery and unique perspective. However, his choice of subjects, particularly young girls, often drew criticism and raised questions about his intentions. Balthus maintained that his paintings were innocent and meant to capture the dreamlike, unguarded moments of childhood. Yet, the provocative nature of his work led to persistent controversy.”

Balthus was born in 19808 in Paris : his parents were Prussian expatriates. His father was an art historian with an interest in Honoré Daumier and has stated that his mother was a Lithuanian Jew (whose father was a Cantor) but later claimed she was of French Protestant heritage. This is one of many examples of how Balthus resisted biographical investigation into his practice usually with an assertion that the work should be considered on its own merits. His sobriquet “Balthus” was derived from a childhood nickname and has been spelled as Baltus, Baltusz, Balthusz or Balthus.

He began drawing at a very early age and has been described as a prodigy by many, and that his artworks never lost a ‘child like nature’ throughout his career : “Balthus never forgot what he had discovered as an 11-year-old: How despair and momentary pleasures could be enlarged into material for art.” (from the Wall Street Journal)

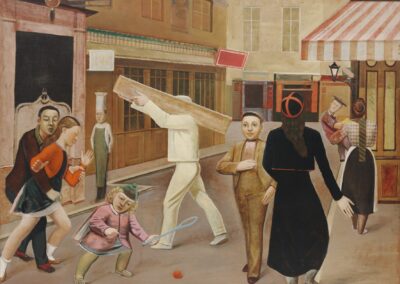

His work was often controversial – even from his first exhibitions, and his painting The Street was censored partly for the depiction of sexual assault but also for the blasé attitude of the other characters in the scene – and a significant part of Balthus’ legacy is an ongoing, often uncomfortable argument about censorship and the perceived intent of the artist in contrast to the viewers’ interpretations of Batlhus’ scenes and figures. In this respect he stands with many of the Surrealists and DADA artists for their equally unsettling artworks.

Balthus’ first exhibition was at Galerie Pierre (Paris) in 1934 : he would regularly show at Pierre Matisse Gallery (New York) from 1938 to 1977. His first major museum exhibition was at the Museum of Modern Art (NYC, 1956). Other notable exhibitions of his work were mounted at Musée des Arts Decoratifs, Paris (1966); Tate Gallery, London (1968); La Biennale di Venezia (1980); Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (1980); Musée cantonal des beaux-arts de Lausanne (1993); Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (1984, traveled to Metropolitan Museum, Kyoto); Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (1984); and Palazzo Grassi, Venice (2001).

Two major retrospectives are worth noting : the previously mentioned Balthus: Cats and Girls: Paintings and Provocations was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2013 – 2014) and another major retrospective overseen by the artist’s wife, Ideta Setsuko was mounted at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (2014).

In 1996 Damian Pettigrew produced a film titled Balthus Through the Looking Glass : this was a documentary shot over a year – including conversations with the artist and with vignettes of Balthus working in his studio – in Switzerland, Italy, France and England.

From ArtReview : “Balthus’s depressive, prurient weirdness casts everything as passive and de-energised, even to the point of suggesting the perspective of a viewer in a state of psychological disintegration [….] Objectification is a state Balthus seems to revel in, and it’s never really clear whether these paintings ever transcend this pathological sense of a narcissistic sensibility willing itself into lifelessness. Nevertheless, that these paintings succeed in letting us in on this lonely, arrested worldview makes them worth seeing, as a reminder of the dubious, sometimes obscene power of images.”

More of Balthus’ work can be seen here, more about his life can be read here and a site devoted to his legacy can be seen here.

Nearly a century after the creation of many of his artworks, Balthus’ paintings “continue to spark discussions about artistic freedom, the portrayal of youth, and the boundaries of decency.” (from here)