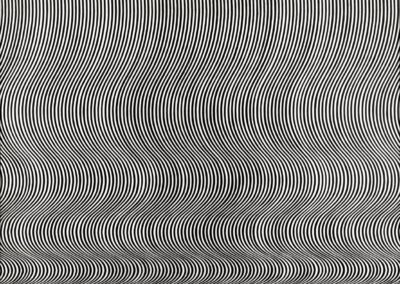

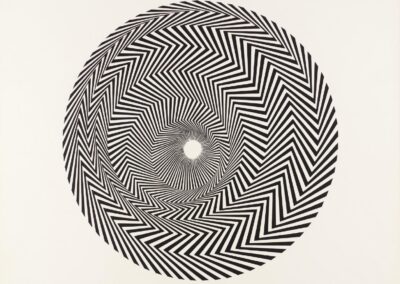

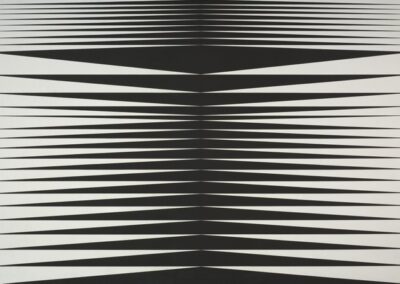

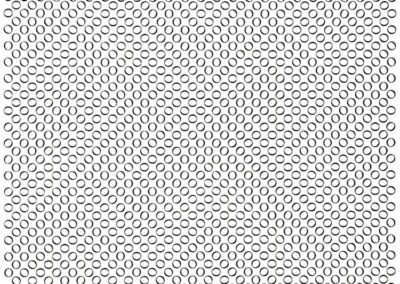

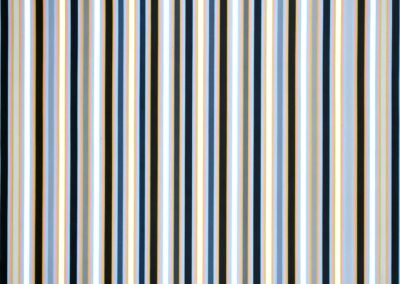

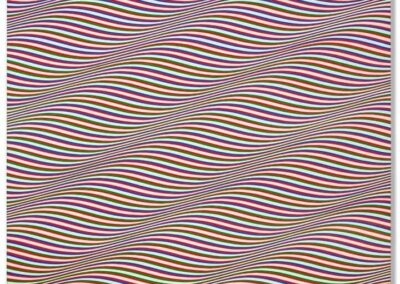

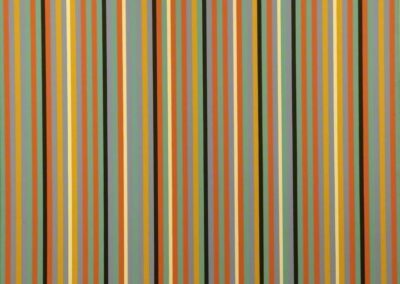

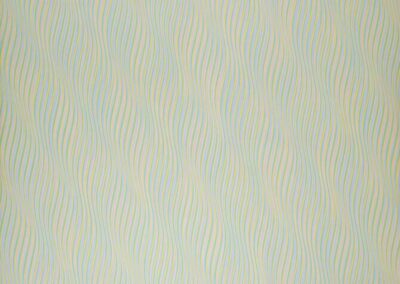

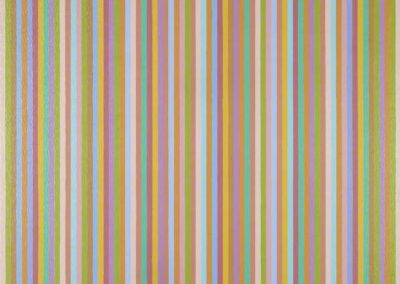

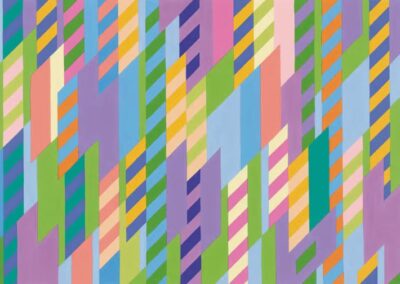

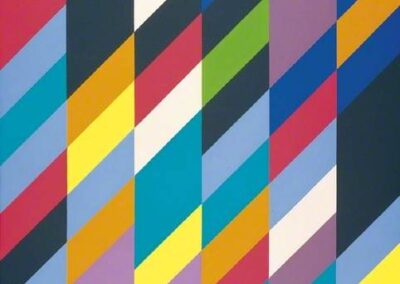

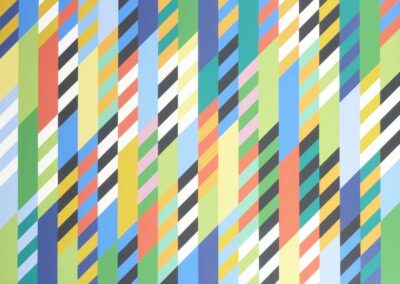

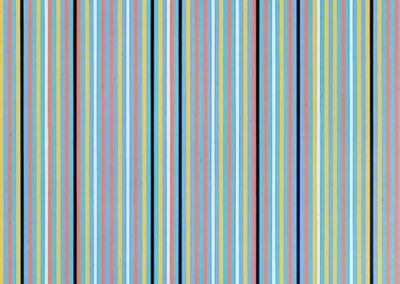

The next Artist You Need To Know is Bridget Riley.

Riley is an English painter known for her Op Art paintings that are immediately recognizable and that both enthrall and discombobulate the viewer. A groundbreaking artist in post WW II Britain, Riley’s bold works are a landmark in the history of art in the western canon and still influential today. she was the first woman to win the painting prize at the Venice Biennale in 1968

In 1971, the British art critic and journalist Robert Melville stated that “No painter, dead or alive, has ever made us more aware of our eyes than Bridget Riley.”

Often spoken about in tandem with the like minded artists Richard Anuszkiewicz and Victor Vasarely, Riley is arguably the most impressive painter in the Op Art Movement that began in the late 1950s. Riley’s aesthetic began to form with an interest in optical effects when she encountered the paintings of the artist Georges Seurat and his unique use of pointillism (“I always took care to learn from the past, to look carefully at what other painters had done and why, at how they got there”). She worked initially in black and white before beginning to explore colour in the mid 1960s. Riley’s “work shows a complete mastery of the effects characteristic of Op art, particularly subtle variations in size, shape, or placement of serialized units in an all-over pattern.” (from here)

“For me nature is not a landscape, but the dynamism of visual forces – an event rather than an appearance.”

Riley was born in 1931 in London (UK). Her father was a printer who owned his own business as well as an officer in the army : when her father was mobilized during WW II, the family moved to live with an aunt in Cornwall. The aunt had attended Goldsmiths College in London, and Riley attended talks given by a range of retired teachers and other individuals within the cultural sphere who were part of her aunt’s circle. During this time, Riley was free to wander the countryside and ‘she would claim that these early experiences roaming the countryside, spending hours watching cloud formations and the shifting light throughout the day, strongly informed her artistic practice.’

She would later attend Goldsmiths College (1949 to 1952) and the Royal College of Art (1952 to 1955). During her time at the latter, she met fellow students Peter Blake and Frank Auerbach. During her time in the tumultuous and exciting London art scene, Riley would speak of this period later as a difficult time for her as she was consumed – like many artists of her generation with the question of “What should I paint, and how should I paint it?”

Riley worked in a glassware shop for a period before joining the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency where she worked as illustrator until 1962. She also returned home to care for her ailing father, and the respective emotional and physical demands of this period led to an emotional breakdown from which she recovered after a brief instituionalization.

During this same period, the Whitechapel Gallery mounted an exhibition of Jackson Pollock’s painting (in 1958 specifically) and experiencing this work had a major impact on her development as an artist.

“I couldn’t get near what I wanted through seeing, recognizing and recreating, so I stood the problem on its head. I started studying squares, rectangles, triangles and the sensations they gave rise to.”

During this same formative period, Riley discovered the ideas of Harry Thurbon. He was a teacher at the Leeds School of Art and “was a proponent of a new form of arts education that moved away from romantic ideas of expression toward concrete skills, embracing a connection to professional contexts, such as illustration and design. Thurbon’s ideas echoed the much earlier ideas of form and function taught at the Bauhaus, which was an important inspiration in early Op art.” (from here) Riley would participate in Thurbon’s workshops in Norfolk where she met and began a relationship with artist, writer, and educator Maurice de Sausmarez. He would be somewhat of a mentor to Riley, expanding her knowledge of art history and helping her to build the base that would launch her unique style.

In 1962 Riley’s exhibition at Victor Musgrave’s London Gallery was a massive success and she would consistently be included in shows that would be defining touchstones for British Painting for the next few decades. One of the most notable of these was the 1963 New Generation exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London with other important contemporaries like Allen Jones and David Hockney.

Three years later she would have a huge exhibition at the Richard Feigen Gallery and was also prominently featured in the MOMA’s important show Op Art The Responsive Eye. This was an impressive debut of Riley’s artwork in North America.

But this period also saw one of the more ugly moments of Riley’s artistic career. From here: “In later accounts, Riley recalled her drive from the airport to the museum, passing shop window after window with dresses whose fabrics were inspired by Op art or, in some cases, taken directly from her paintings. Despite the affinity between many Op art artists and the textile and design industries, she was dismayed by the commercialization of her work and claimed “the whole thing had spread everywhere even before I touched down at the airport.” She tried to sue the designers of one of the dresses, but was unsuccessful. Riley said at the time that “it will take at least 20 years before anyone looks at my paintings seriously again.””

This insidiously swift commercialization of Op art hurt both Riley’s career as her aesthetic was too often dismissed by supposedly serious artists and the larger establishment as being simply ‘fashion’ and not the rigorous attempt to redefine painting for both herself an in a larger historical context that challenged the status quo while also being firmly grounded in a strong art historical knowledge.

“The music of colour, that’s what I want.”

In the late 1960s, Riley began to introduce colour into her compositions, in tandem with her ongoing work in form and space. In the early 1980s she traveled to Egypt : the artworks she encountered there – “the colors are purer and more brilliant than any I had used before” – enthralled her, as well as the idea that “Egyptian artists managed to use only a few colors to represent what she described as the “light-mirroring desert” around them. Her paintings after this trip contained a freer arrangement of colors than she had previously used and a palette inspired by the Egyptian art she had seen.” (from here)

Over the next few decades Riley would expand her practice to include commissioned murals : despite the decline of Op art in North America, her work continued to be shown in the UK and this expanse into more public spaces – with these public artworks in places such as hospitals – speaks to the amenable nature of her aesthetic.

“The eye can travel over the surface in a way parallel to the way it moves over nature. It should feel caressed and soothed, experience frictions and ruptures, glide and drift. One moment, there will be nothing to look at and the next second the canvas seems to refill, to be crowded with visual events.”

Riley has garnered a number of awards through her career. These include being named a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (1974), honourary doctorates by Oxford (1993) and Cambridge (1995), the Praemium Imperiale (2003) and is one of only 65 Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour in the Commonwealth. In 2009 she was awarded the Goslarer Kaiserring and in 2012 was recognized with the 12th Rubens Prize of Siegen. That same year Riley broke further ground as the first woman honoured with the Sikkens Prize.

We’re sharing a few installation images below of past exhibitions of Bridget Riley’s work (from the Pace Gallery) to give a more genuine sense of the scale and impact of her work.

Riley’s artworks are represented in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Tate Gallery in London, The Art Institute of Chicago, The Dallas Museum of Art, Moderna Museet, The Museum of Fine Arts (Boston), Walker Art Gallery (Minneapolis), The Scottish National Gallery and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice.

She is still working – in her early 90s – from her home in South Kensington (her residence had long ago been converted so that four out of the five floors are studio spaces). Artists as diverse as Damien Hirst and Rachel Whiteread have cited her as being important to their own practices, as much for her innovation as her prolific and dedicated practice.

In this same manner, the group that she co founded in 1968 – more than half a century ago – with fellow artist Peter Sedgley titled SPACE is still serving artists and the larger artistic community in London today. Riley’s sense of community was further on display when, as a board member of the National Gallery in the 1980s she was instrumental in preventing the conservative government of Margaret Thatcher’s spurious plan to ‘gift’ adjacent land to developers : this site is now instead the museum’s Sainsbury Wing.

“The pleasures of sight have one thing in common—they catch you by surprise. They are sudden, swift, and unexpected.”

There is a very informative page about Riley’s art and aesthetics at The Art Story and more of her works can be seen here. A more extensive accounting of her exhibitions and accomplishment can be seen here.