The next Artist You Need To Know is El Anatsui.

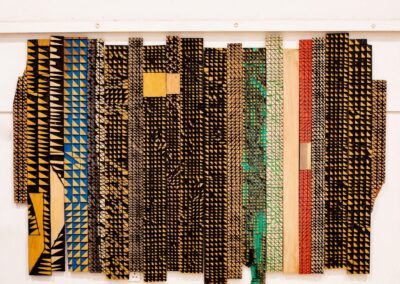

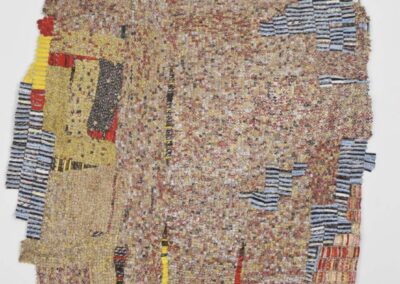

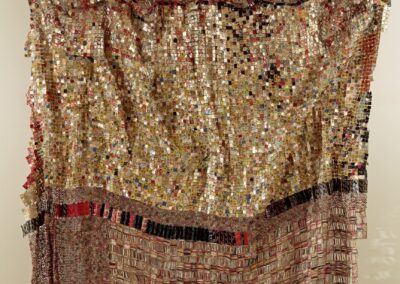

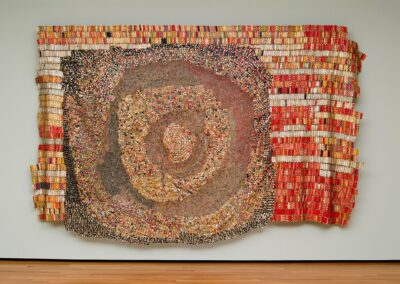

El Anatsui is a Ghanaian sculptor who for the majority of his artistic career has been based in Nigeria. Best known internationally for his “bottle-top installations”, these massive artworks / installations “consist of thousands of aluminum pieces sourced from alcohol recycling stations and sewn together with copper wire, which are then transformed into metallic cloth-like wall sculptures. Such materials, while seemingly stiff and sturdy, are actually free and flexible, which often helps with manipulation when installing his sculptures.” (from here)

“Art is a reflection on life. Life isn’t something we can cut and fix. It’s always in a state of flux.”

The youngest of 32 children, El Anatsui was born in Anyako in 1944 in the Volta Region of Ghana : his mother died when he was young and his uncle became his primary parent. His early drawings (done in chalk on various chalkboards) attracted the attention of the headmaster of his school who encouraged him at a very formative stage. The nature of how the letters were more form, shape and colour than writing was an early aspect of how he would be attracted to abstraction and form in his work as an adult.

Anatsui earned a B.A (1968) from the College of Art and Built Environment in Kumasi, Ghana, and a postgraduate diploma in Art Education (1969) from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), also in Kumasi. At the start of his artistic career, Anatsui was influenced by artists such as Oku Ampofo, Vincent Akwete Kofi, and Kofi Antubam : he was attracted to how they worked in a formal manner that was more in tune with indigenous art forms of his country and region, and less defined by foreign and colonial art movements. Many African nations were seeking and obtaining independence from British rule post WW II and into the 1960s, and this surely helped shape Anatsui’s ideas and aesthetic.

In 1969, Anatsui began teaching at Winneba Specialist Training College (now University of Education), and in 1975 would take up a teaching position at the University of Nigeria. Seven years later he became a senior lecturer for the Fine and Applied Arts department at this university, then head of the department and a full professor of sculpture in 1996. Anatsui would hold this position until 2011.

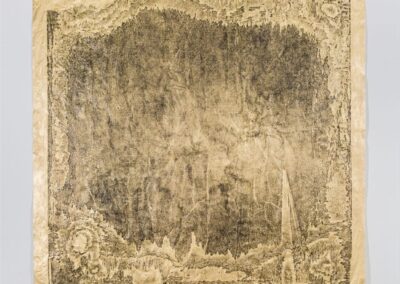

During this time he became affiliated with the Nsukka group. They were “known for working to revive the practice of uli and incorporate its designs into contemporary art using media such as acrylic paint, tempera, gouache, pen and ink, pastel, oil paint, and watercolor. Although traditionally uli artists were female, many of the artists of the group were male. Some were poets and writers in addition to being artists.” (from here)

The words of arts writer Megan Conway (from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) :

“To stand in front of El Anatsui’s Black River [the first image in the gallery above] is to face a shimmering and rippled wall, its effect immediate and sublime. But this majestic tapestry is not made of precious metals; these are used bottle caps and wrappers from beer and liquor distilleries near the artist’s studio in Nsukka, Nigeria, stitched together with copper wire by dozens of studio assistants.

Anatsui was inspired to use bottle caps after finding a plastic bag full of them by the side of the road, and has since created many works similar to Black River. These pieces are changeable, not meant to be static or even final: every time they are draped, they look different. The artist leaves it to others, usually curators, to decide how his sculpture should hang on a wall or be placed on a surface. This trust in collaboration is a rare and humble conviction […] Anatsui himself has made the historical connection between liquor and the transatlantic slave trade; I think of quilts, their making and how they hang in a gallery, like curtains; traditional African textiles, like kente cloth from Ghana, where Anatsui was born; consumerism; alcoholism; transforming trash into something exalted.”

“When something has been used, there is a certain charge, a certain energy, that has to do with the people who have touched it and used it and sometimes abused it. This helps to direct what one is doing, and also to root what one is doing in the environment and the culture.” One might argue that Anatsui is not interested in the Western art historical canon of the readymade (as in the style and aesthetic of Marcel Duchamp) but uses objects and elements specifically to cite their history in both a colonial and economic sphere of reference.

He has exhibited around the world, including the Brooklyn Museum (2013); the Clark Art Institute (2011); the Rice University Art Gallery, Houston (2010); the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2008–09); the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (2008); the Fowler Museum at UCLA (2007); the Venice Biennale (in both 2006 and 2007); the Hayward Gallery (2005); the Liverpool Biennial (2002); the National Museum of African Art (2001); the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (2001); the 8th Osaka Sculpture Triennale (1995); the 5th Gwangju Biennale (2004); the Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha (2019); and the Kunstmuseum Bern (2020).

One of the most notable of his exhibitions was a 2010 retrospective – When I Last Wrote to You About Africa – which was organized by the Museum for African Art and opened at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. This exhibition would travel to numerous venues across the United States for the next three years, with its final iteration being at the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

His works can be found in many museums and public collections. These include the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the de Young Museum (San Fracisco), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, the Museum of Modern Art (NYC), the National Museum of African Art (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC), the British Museum and the Vatican Museum.

In 2023 he was awarded the Hyundai Commission by Tate Modern. You can watch a video about that artwork – titled Behind the Red Moon – here. We’ve also included some images of this work (from the Tate) below to give a better sense of the sheer scale of Anatsui’s artworks.

El Anatsui’s web site can be found here. It offers a more comprehensive listing of his accomplishments (including international awards and exhibitions) and many images (including installation documentation of his work, that offer different iterations of his art and gives a more nuanced impression of the sheer scale and nature of his art as well as details about the unique materials the artist employs).