Our next Artist You Need To Know is George Grosz (1893 – 1959).

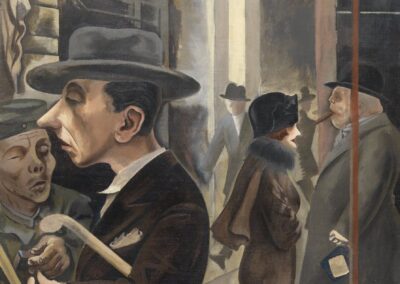

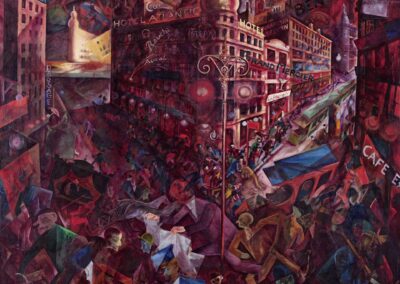

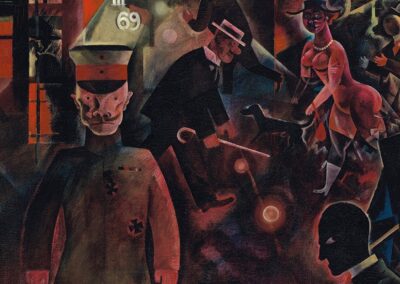

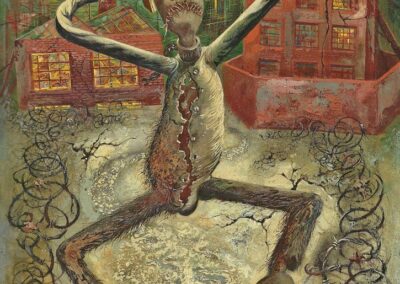

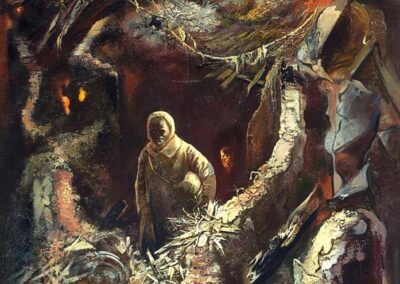

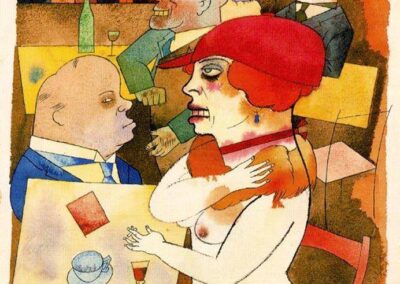

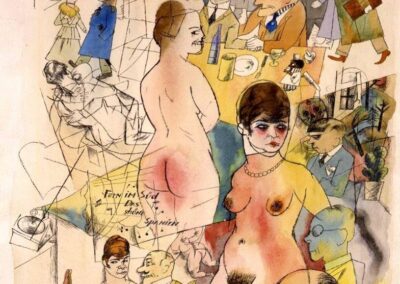

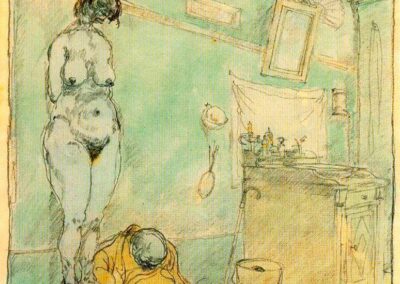

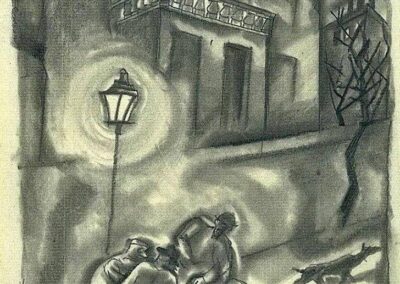

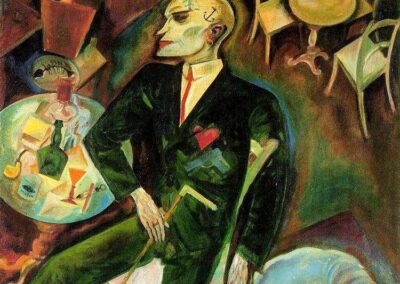

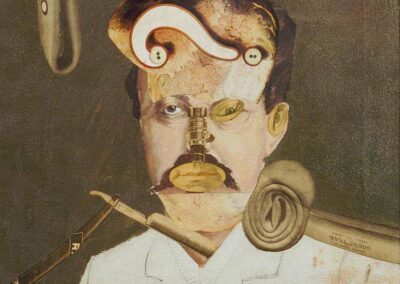

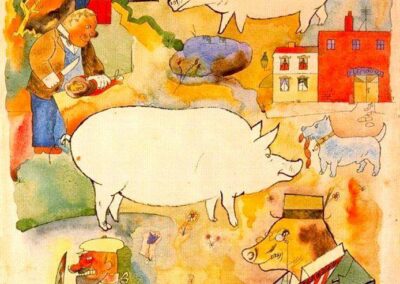

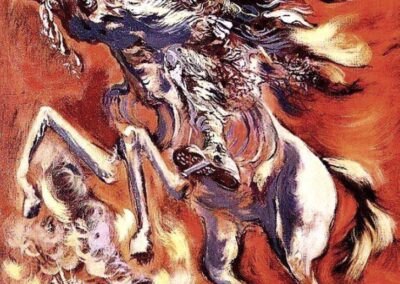

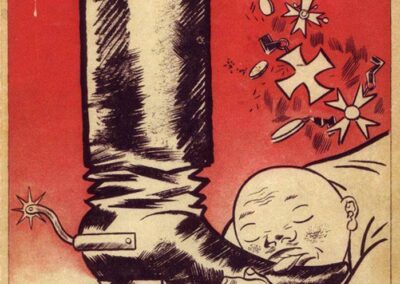

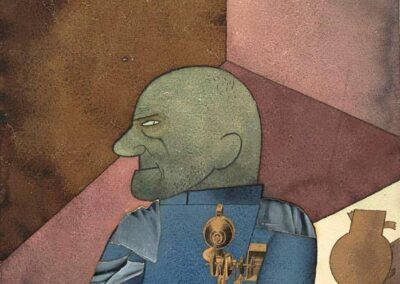

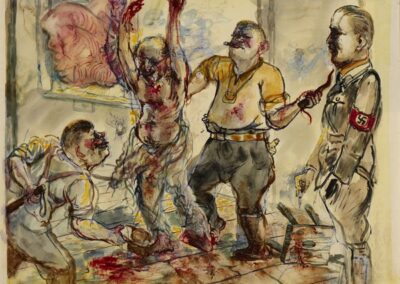

Grosz (born Georg Ehrenfried Groß) was a German artist renowned for his drawings and paintings of Berlin, especially in the 1920s and capturing post WW I Germany, that employed satire and caricature in a style that was both humourous and viciously insightful. Grosz was a significant member of the Berlin Dada and Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movements (the latter in tandem with Otto Dix and Max Beckmann) that helped define the Weimar Republic’s cultural sphere with an unflinching – sometimes even grotesque – record of that period.

“…I considered any art pointless if it did not put itself at the disposal of political struggle….my art was to be a gun and a sword.”

He was the youngest of three children (two older sisters) and for the early part of his life the family moved between Berlin (where his parents ran a public house until it failed) and Stolp (a rural northeastern coastal town now located in Poland) until his father’s death forced Grosz and his remaining family to return to Berlin. His mother and sisters supported the family through their work as seamstresses in that city, but they would return to Stolp in 1902 when his mother found employment with a Hussar regiment. This was surely a factor in how his many early drawings had a boy’s fascination with the military, uniforms and historic battles. One can see how these early child like and childish fantasies would both shape his more mature work, both in terms of subject matter and a certain skepticism – or even cynicism – for which Grosz is known.

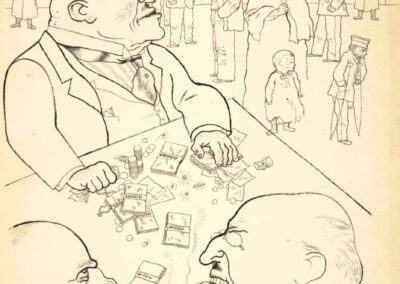

Grosz attended the Dresden Academy of Art : but outside of the academic environment he began to work in a more graphic and satirical style of caricature. He was “strongly influenced by Jugendstil (Art Nouveau), magazines, and cartoon illustrations. He greatly admired illustrations in Ulk, the humorous supplement of the Berliner Tageblatt that also featured Grosz’s first published drawing in 1910.” (from here)

He graduated from Dresden in 1911 and returned to Berlin where he attended the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts). During this period he was unfamiliar with some of the more avant-garde groups such as Die Brucke and Der Blaue Reiter, preferring instead to document the life and people of the city (especially the working classes and the poor) in a more immediate and realist manner with none of the political commentary that would inform his mature work. Several years later, in 1913, Grosz spent a brief period in Paris at the Académie Colarossi.

And then came the first World War in 1914 which would be an indelible moment in Grosz’ art and life and neither would ever be the same afterwards.

“I thought the war would never end. And perhaps it never did, either.”

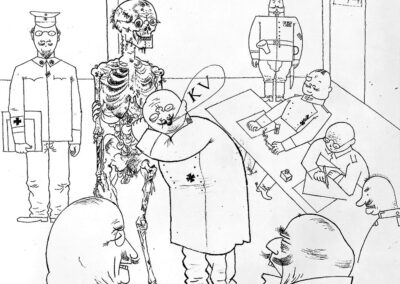

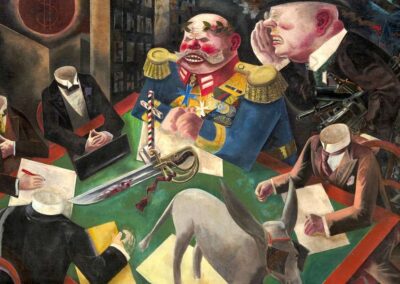

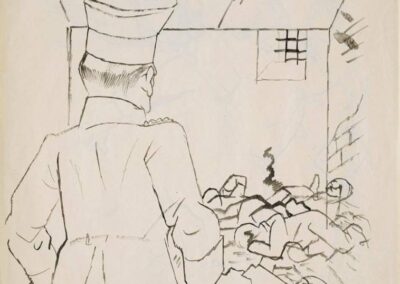

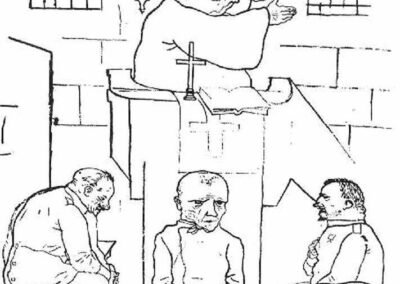

From here: “Seeing the war stories of his childhood come to life in the beginnings of World War I, Grosz joined the army in 1914, but was discharged after six months due to sinusitis. Cynical drawings, such as The Faith Healers (1916), documented his own experiences as a soldier and clearly demonstrated the dissolution of his idealistic beliefs regarding war. In order to both distance himself from his German roots, and to proclaim his affinity for American culture, Georg Groß had his name legally changed to George Grosz in 1916. He was recalled to active duty in 1917, but was permanently released after an obligatory stay in a psychiatric facility. Disillusioned by a human predisposition for violence he observed during World War I, Grosz’s drawings became even more explicit, expressing his shock and disgust. He was inspired by earlier political and social satirists like Honoré Daumier and William Hogarth, and aspired to become the 20th-century German equivalent of these renowned artists. Along with his colleagues Wieland Herzfelde and John Heartfield, he joined the Communist Party of Germany and developed a political satire magazine called Die Pleite (Bankruptcy).”

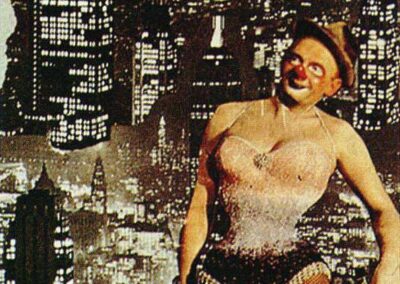

In 1919, Grosz joined the Dada movement in Berlin and he was an important member of that group, being an active participant in the first Dada publications, exhibitions, and actions. He also – in collaboration with the aforementioned Heartfield – expanded and refined the medium of photomontage that served as both artworks and propaganda. Grosz had a warrant out for his arrest during this time for his activities and consequently was in hiding for a time, but this didn’t stem his artistic production as he continued to produce ‘cartoons’ and other visual political commentary of numerous magazines.

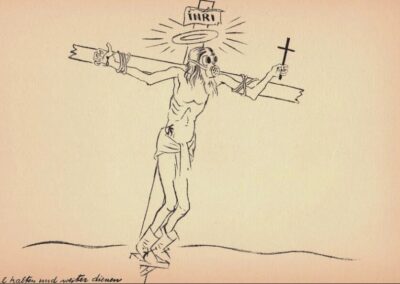

Grosz’s first one-man show took place at Goltz’s Galerie Neue Kunst in 1920 : he would also marry the artist Eva Peter that year, and they would collaborate on a number of images that continued to explore controversial and transgressive topics. When a number of their works were displayed at the First International Dada Fair in 1920, Grosz – and many others involved with the event were ‘put on trial’ and subsequently ‘punished’ with a fine for “grossly insulting the German army.” This didn’t intimidate Grosz in the least : he would produce another body of work titled Ecce Homo (1915 – 1922) that led to dismissive accusations of ‘pornography’ and further fines.

Despite these repressive attempts at censorship in his native country, Grosz was recognized internationally in the 1920s as one of Germany’s most significant artists, especially in the sphere of political dialogue and social issues. But with the ongoing rise of the Nazis and the violent chill in Germany with that group fomenting political instability, Grosz spent some time in Russia and France and then taught briefly at the Art Students League of New York, in the United States, in 1932.

He returned to Germany in late 1932, but with Adolf Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933 Grosz made the permanent move with his family (he had two sons with Eva Peter) to the United States. Grosz taught as well as continuing his illustration work with magazines like the New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and Esquire. He was awarded a grant from the Guggenheim Museum in 1937.

Sadly, back in Germany, the Nazis’ Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition of 1937 (which took place in Berlin) attempted to belittle the artist and the majority of his works in that show were destroyed by the fascist government.

He would not return to Berlin for nearly three decades.

In the United States, Grosz enjoyed critical recognition with a retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1941 : sadly, financial security did not come with this praise, and despite being acknowledged as “a hero of the people in Germany” (and now being seen as an important American artist, as he became a US citizen in 1938), he would support himself through teaching for most of the rest of his life. Grosz taught at the Arts Students League and over the next two decades he also taught at Columbia University, the Skowhegan School of Art, and the Des Moines Art Center.

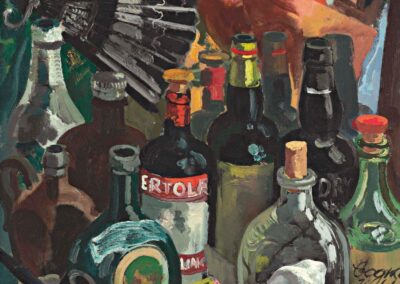

Grosz’ later years were marked by depression and alcohol abuse : some art historians offer that this was fueled by his doubts that his work had fostered any real change, and during these decades he often eschewed political and social issues in his work and produced softer and more sentimental – perhaps even romantic – landscapes and less edged drawings than previous. But “some of his last pieces from 1958 were photomontages and hearken back to his earlier Dadaist aesthetic and message, passing judgment upon consumerism and suggesting that his absorption with American culture had ended in disappointment.” (from here)

His resolve to return to Berlin – which had always been important to him, during his exile in the US – came to fruition in 1959 : but shortly after his return to what Grosz always considered his home he died as a result of a fall down the stairs after a bout of excessive drinking.

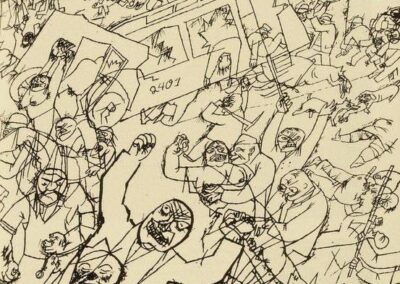

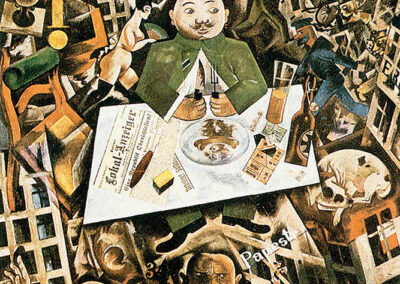

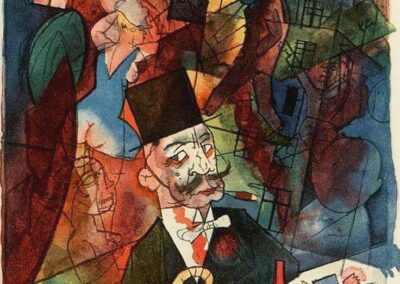

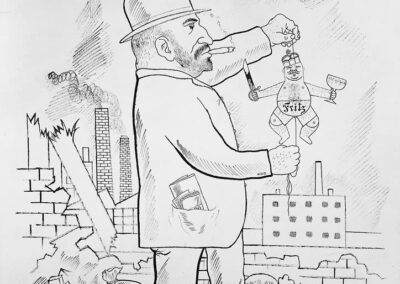

The art critic Trewin Copplestone offered the following about Grosz’ aesthetic : “A deeply disillusioned man, he saw humanity as essentially bestial and the city of Berlin as a sink of depravity and deprivation, its streets crowded with unprincipled profiteers, prostitutes, war-crippled dregs and a variety of perverts. A communist, his feeling of social outrage stimulated him to produce the most biting drawings and paintings.”

Much more about George Grosz’ artwork – and his ongoing relevance and importance even nearly a century after some of his most famous works – can be seen here. If you’re within the social media sphere of FaceBook, there is a fine gallery of Grosz’ work from The Museum Without Walls / Le Musée Imaginaire which can be enjoyed here. This gallery also offers comments and information about many of the individual images.

We’ve included more images than usual in this post as Grosz was a prolific artist in terms of his cartoons and drawings, and was less a painter than a graphic artist (in a style that would see his legacy continued by someone like Art Spiegelman, for example).

The art historian and critic Robert Hughes offered the following about Grosz’ work : “In Grosz’s Germany, everything and everybody is for sale. All human transactions, except for the class solidarity of the workers, are poisoned. The world is owned by four breeds of pig: the capitalist, the officer, the priest and the hooker, whose other form is the sociable wife. He was one of the hanging judges of art.”