Our next Artists You Need To Know are the group known as the Hairy Who (1966–1969, also sometimes called The Chicago Hairy Who) : Art Green (b. 1941), Gladys Nilsson (b. 1940), Jim Nutt (b. 1938), Jim Falconer (1942 – 2022), Suellen Rocca (1943 – 2020) and Karl Wirsum (1939 – 2021).

They were six artists who worked under the umbrella of The Chicago Imagists (which also birthed The Monster Roster) which was a larger movement in the Chicago area in the 1960s with two loose defining aspects of association with the Art Institute of Chicago and an interest in representational art. The Hairy Who all enjoyed a somewhat irreverent approach to words and ideas, and the origin of the group’s name is credited to when Wirstum – in the midst of a heated discussion about a local Chicago art critic Harry Bouras – dismissed him by asking “Harry who?”.

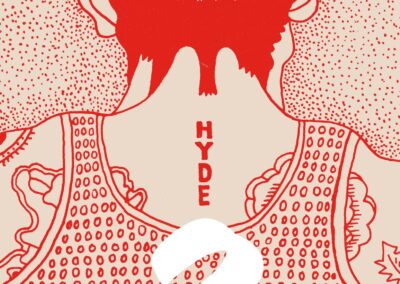

As recent graduates of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the six banded together “mounting unconventional displays of bright, bold graphic work at the Hyde Park Art Center on the city’s South Side. Over a period of four years, they transformed the art landscape of Chicago, injecting their new and unique voices into the city’s rising national and international profile.” (from the Art Institute of Chicago)

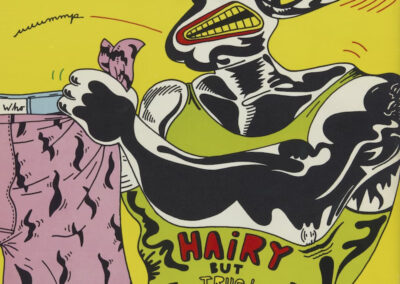

The Hairy Who were fond of creating limited edition ‘comic books’ (what we might now call the zine format) as an alternative to the more expensive and formal catalogs common to galleries as both unique artworks but also as a more economical documentation of their projects. Many of the images we’re sharing here are from those works. Their in person exhibitions had numerous individual works from the respective artists, but these promotional and archival booklets are in many ways more representative of the group’s collaborative aesthetic.

Art Green, in considering his time with the group, wryly offered that “No, we didn’t want to overthrow anything, we weren’t mad at the museums particularly, we didn’t have a manifesto, we didn’t have a mission statement. But we made things we wanted to look at, you know?”

Expanding this idea, Jim Falconer in considering the time and place within which the Hairy Who emerged, commented that “Chicago seems to me (with the great advantage of hindsight) a place to invent your world. A place that is far enough away so that you could misunderstand the rest of the world and a place unique enough to provide an actuality which no other place will. To use a title from a Sun Ra record, a place where angels and demons are at play, perhaps on the same team.”

The artists of Hairy Who were part of a generation who were responding to a period of change in Chicago, the United States and the wider world : the war in Vietnam, the assassination of political figures, protests by students on campuses as well as wider demonstrations as regards race and gender equality and the rise of a counterculture and consumerism.

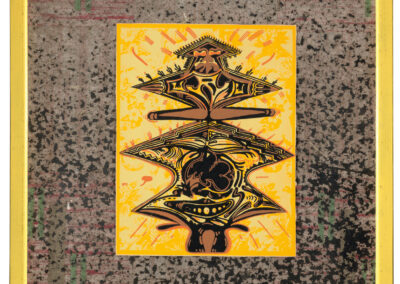

The Hairy Who, between 1966 and 1969, mounted six “uninhibited and informal exhibitions—three in Chicago and one each in San Francisco, New York, and Washington, DC…..Their work—vividly unbridled yet also formally refined—embodied irreverence and youthful fearlessness…..they were unconcerned with art world trends or any of the movements coming out of New York City at that time : elements of the grotesque, the excessive and fantasy (more in tune with both comics and with a nod to the Surrealism that was part of the Chicago Imagists from which they emerged) are all hallmarks of their work.” (from the Art Institue of Chicago)

Chicago writer and editor Christine Newman, writing of the Hairy Who in response to one of their ‘events’, stated that even with the group’s awareness of larger cultural trends, they “made their own way, staking out their time, their place, and their work as an unforgettable happening in art history.”

Each artist had their own respective styles.

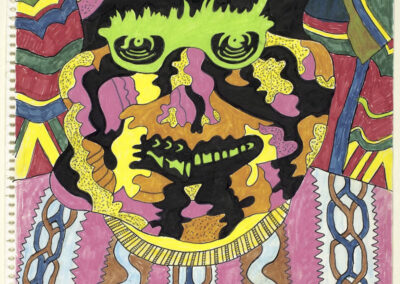

Karl Wirsum’s artworks often were dominated by “a single, central, confrontational figure set against a monochromatic background. His figures are never fully human, but rather a humanoid mash-up of robots, aliens, and totemic forms.

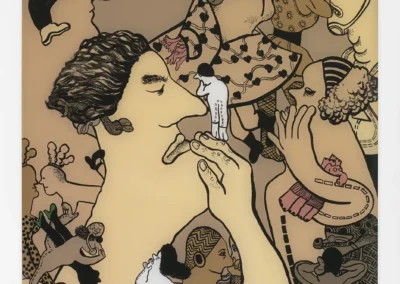

In Jim Nutt’s work, the unruliness of the human form is front and center—pimples erupt, sweat splashes off, and hairs sprout like a crop of microgreens. Yet the vulgarity in his images, from their gory details to their locker-room humor, is always offset by the artist’s technical prowess. Every one of Nutt’s compositions is planned with the utmost care.

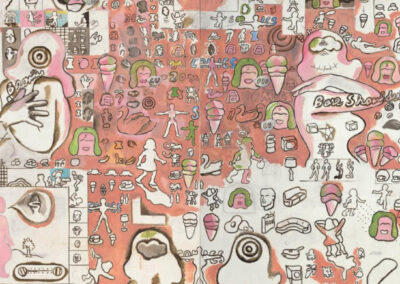

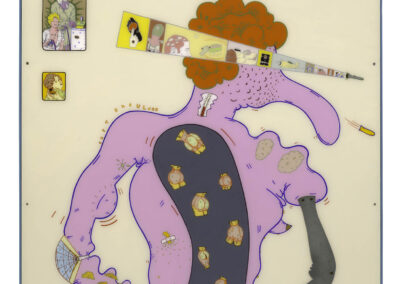

Suellen Rocca has described her own work as a form of picture writing, akin to hieroglyphs. Her paintings are composed of repeated, gendered motifs; inspired by cultural icons of beauty and romance in mass media, handbags, lipsticks, and palm trees speak to popular culture through a personal lens.

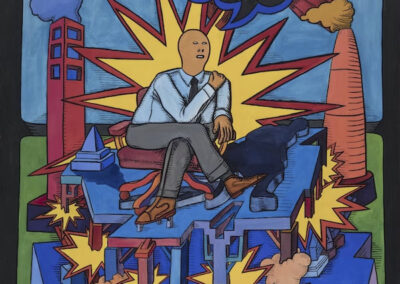

While every member of the Hairy Who wrestled with the sociopolitical tensions of the 1960s, [Jim] Falconer was perhaps the most overtly political. Falconer’s drawings and paintings from 1966 to 1968 are full of images from pop culture rendered in a floppy, wiggly style and hallucogenic colors.

Gladys Nilsson‘s characters—either human, animal, or a hybrid in between—play, fight, and flirt in fantastical landscapes where greenery and objects float free from gravity. The figures themselves seem made of rubber, limbs stretching to the picture’s edge, looping around anything nearby. Nilsson’s work speaks of relationships: the relationships between the figures, forms, and textures.

As a student, Art Green studied Giorgio de Chirico in Chicago’s public art museums. The Italian painter’s dreamlike narratives and odd juxtapositions are evident in Green’s work; his early paintings layer images within images, using visual devices like zippers or curtains that open to reveal a hidden scene. What’s revealed, however, is often more of the same advertising imagery, as though superficiality was all there ever was. In his later work, Green’s compositions become increasingly dense, with the intricacy and geometry of a mosaic, or a tapestry.”

(The text above are all excerpts from longer biographies of the artists, from here).

Jim Nutt, in speaking of the unique styles of the artists in the group, pointed out that “the only way our work looks related is if you compare it to the standard of an all-black painting by Ad Reinhardt.” This seemingly facile comment actually encapsulates the playful disdain that Hairy Who had for ‘high art’ conversations and the ‘proper’ gallery space, and how they often sampled and re interpreted pop culture and more immediate and populist media of the everyday into their art and aesthetics.

Writer and cultural critic Edmée Lepercq offers the following summation of the group, decades after their exhibitions and happenings, as a testament to their impact :

“If New York Pop art was considered cool, Chicago’s was hot, embodied in the mid-1960s by six recent graduates from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago who exhibited together under the moniker “the Hairy Who.” While Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein treated mass consumerism and popular culture with irony and distance, the Hairy Who were interested in the emotional charge of such imagery. One was personal, the other aloof.

The Hairy Who were united by their education, their sense of humor, their craftsmanship, and their knowledge of art history. Their sources were as eclectic and far-ranging as Art Brut, Surrealism, sale catalogues, bodybuilders, and medical illustrations. Today, the Hairy Who are renowned for their hallucinatory representations of the body, which shows it fragmented, elongated, and exaggerated. Their works often depict mutilations and skin diseases, which sit in stark contrast with their otherwise cheerful aesthetic. The dissonance perfectly captures the tensions between the relentlessly upbeat fantasy world of American consumerism and the political upheaval of the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Chicago itself was an epicenter of racial tension throughout the 1960s following desegregation attempts by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others.

Though the collective exhibited together for just three years, from 1966 to 1969, they drew national and international attention and catalyzed the broader Chicago Imagist movement, which extended into the 1980s. Rather than a series of group shows, their exhibitions challenged traditional modes of installation with artists covering gallery walls with flowery linoleum and hanging oversized price tags on paintings and drawings. Each exhibition came with a comic book–style publication—a dig at stuffy exhibition catalogues—as well as buttons and posters. It was a far cry from the white cube.”

In 2014, a documentary about the Hairy Who and Chicago Imagists revived interest in the artists and their work : this led to an exhibition that spanned 2018 to 2019, presented by the Art Institute of Chicago that was the first major showing of the artists’ works during this period. A number of other exhibitions – for which the artists re united briefly – were to follow from this spate of interest, but each artist returned to their own work and careers afterwards, in a nod to the ephemeral and loose nature of the Hairy Who.

The art of the Hairy Who members is “not ironic, but neither is it solemn,” curator Dan Nadel wrote in the catalogue for a 2015 exhibition at the Hyde Park Art Centre in Chicago, “It is warm but not sentimental, immaculately crafted but not cold. It is art that embraces mundane realities, wet sexuality, fantastic realities, and a hard-edged spirituality. It asks for nothing from the viewer, makes no special cases, and yet is not against or for anything.”

Several engaging biographies of the individual artists who comprised the group – including their careers and achievements post Hairy Who – can be seen here. As well, an exploration of the Art Institute of Chicago’s site will offer more information and images both about the group and the respective artists.

A short video about the group can be enjoyed here.