Our next Artist You Need To Know is Hannah Höch (1889 – 1978).

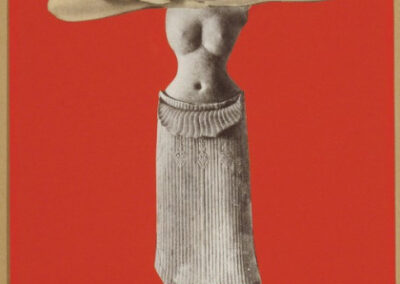

Höch is arguably one of the best known of the German Dada artists of the early twentieth century, and specifically the Weimar period (1919–1933) in Germany. She developed the process of photomontage (also known as fotomontage), where the components are photographs, or photographic reproductions pulled from the press and other widely produced media. “Höch’s work was intended to dismantle the fable and dichotomy that existed in the concept of the “New Woman”: an energetic, professional, and androgynous woman, who is ready to take her place as man’s equal. Her interest in the topic was in how the dichotomy was structured, as well as in who structures social roles.” (from here) Höch’s art also focused upon themes of androgyny and the fluidity of gender and especially political events and dialogues around them. She’s a groundbreaking artist not just for her work in photomontage but also for the prevalence of feminist ideas that are intrinsic to discussions – and action – which encouraged the liberation and agency of women during the pre WWII Weimar Republic and nearly a century later.

“I have always tried to exploit the photograph. I use it like colour, or as the poet uses the word.”

Anna Therese Johanne Höch had a rather typical beginning: her mother was an amateur painter, but she was born into an upper-middle-class family in southeast Germany, the eldest of five children who left school at 15 to help her parents care for her siblings. Höch would comment later in her life that her father believed that “a girl should get married and forget about studying art.” In 1912 she attended the School of Applied Arts in Berlin, studying glass design, sparking an interest in applied arts and design that can be seen in her later work. Her studies were interrupted by WWI, as the school was closed and she joined the Red Cross.

In 1915 Höch returned to Berlin and studied graphic arts at the School of the Royal Museum of Applied Arts under Emil Orlik. That was also an important year in her life as she met the Dadaist artist Raoul Hausmann: their romantic relationship would be tumultuous and inform the practice of both of the artists. During this period, Höch also met and became close with artist Kurt Schwitters (some art historians claim that it was Schwitters who encouraged her to add the final “H” to her adopted name of “Hannah,” so that it would be palindromic. This sense of play was a tenet of Dadaism and can be seen in much of Höch’s artwork and that of other artists in the movement).

For a decade (1916 – 1926) Höch worked for the magazine and newspaper publishers Ullstein Verlag: specifically in the “department dedicated to handicrafts and designed patterns for crochet, knitting and embroidery. In 1918 she wrote a manifesto of modern embroidery, which encouraged Weimar women to pursue the “spirit” of their generation and to “develop a feeling for abstract forms” through their handwork.” (from here)

Höch soon started to make the photomontage images for which she is best known: in 1918, Höch and Hausmann took a holiday to the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe “where she later claimed to have discovered the concept of photomontage that would be fundamental to her artistic practice. They found images that German soldiers sent home to their families, with pictures of their faces pasted onto the bodies of musketeers. From these she claimed she discovered the power of collage to “alienate” images – that is, to give them new meanings when placed in conjunction with new elements and in new contexts.” (from here)

During the late 1910s and early 1920s she was an essential part of the Dada movement in Berlin.

Despite how her “aesthetic of borrowing from popular culture, dismemberment and collage fitted well with that of the Dadaists, the union was an uneasy one, not least because of the inherent sexism of the movement. She also felt uncomfortable with the exhibitionist element of the Dada circle, and was embarrassed by the behavior of some of her peers.” Often dismissed by other members, she was often ‘tolerated’ solely due to her relationship with Hausmann, which she ended in 1922. As is often the case in art history, Höch is considered a defining artist of a movement that garnered her less respect than she deserved, and is now one of the most appropriately lauded artists of that era.

“Radical movements often espouse the most conservative of values. Dada claimed it was radical, anti-bourgeoise, and anti-capitalist in its aesthetics. But two of its key members (George Grosz and John Heartfield) refused to include any women (or their work) in the movement. Women, they said, were there to make the sandwiches, pour the beer, and give credibility to the men’s sexual attractiveness, while they discussed ideas about art and how to change the world.

Hannah Höch was a woman and she knew how to change the world. But few of the Dadaists were listening. She refused to give in to Mama’s boys Heartfield and Grosz. By her talent and a sheer force of will, Höch became the only female member of the Dada movement. Heartfield and Grosz squealed objections and stamped their tiny trotters over Höch joining their little boys’ club. They claimed they supported women’s rights and equality and all that, but in reality they loathed the idea of a (any) woman being included in their gang.” (from Paul Gallagher’s essay for Flashbak, which we also recommend for its insight).

As the 1920s came to a close Höch was expanding her artistic community and was engaging with contemporaries like Piet Mondrian, Tristan Tzara and László Moholy-Nagy, and was influenced by the De Stijl movement. In 1926, relocated to The Hague in the Netherlands with her partner Dutch writer Til Brugman.

Like several of the artists we’ve featured (Käthe Kollwitz or Charlotte Salomon), Höch found herself attacked by the Nazi party in Germany during their rise to power in the 1930s. Accused of producing ‘degenerate art’, her exhibitions and opportunities were cancelled by ‘local Nazi councils.’ However, she didn’t flee Germany, but returned to Berlin in 1936 – where she would live the rest of her life. Post WW II, Höch shifted both artistically and socially, moving away from her more figurative photomontage pieces and more into abstraction. This period of work is lesser known and not as lauded by critics and historians.

In the early 1970s, art historian Dawn Ades visited Höch in Berlin and commented that the artist was “as interested in nature as she was in art…you had to crawl under apple trees to get through the front door. She incorporated leaves and twigs and other organic matter into her collages of the time.”

Hannah Höch’s artwork has been presented in numerous solo and group exhibitions, as befits someone who helped redefine the art of the Twentieth Century. In 2014, The Whitechapel Gallery in London presented a major exhibition of over one hundred works from international collections that Höch created from the 1910s to 1970s. Other notable exhibitions include Hannah Höch – Auf der Suche nach der versteckten Schönheit, (Looking for the hidden beauty); Galerie und Verlag St. Gertrude (2017, Hamburg, Germany) Hannah Höch – Revolutionärin der Kunst, Kunsthalle Mannheim und Kunstmuseum Mülheim an der Ruhr (Germany, 2016); Vorhang auf für Hannah Höch (Curtain up for Hannah Höch), Kunsthaus Stade (Stade, Germany, 2015); Hannah Höch – Aller Anfang ist DADA (Every Beginning is DADA) (Museum Tinguely, Basel, Switzerland, 2008 and at Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, 2007); The Photomontages of Hannah Höch (Walker Art Center, Museum of Modern Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in Minneapolis, New York City, Los Angeles, respectively, 1997); Hannah Höch (Museums of the City of Gotha, Germany, 1993); Hannah Höch, National Museum of Modern Art (Kyoto, 1974); Hannah Höch: Bilder, Collagen, Aquarelle 1918–1961 (Galerie Nierendorf, Berlin, 1961): and Hannah Höch (Kunstzaal De Bron, The Hague, Netherlands,1929).

Hannah Höch was a prolific artist, and was creating work and exhibiting them internationally until her death in 1978, in Berlin. In 2017, to mark the 128th anniversary of her birthday, a Google Doodle was created in her honour.

Alina Cohen, writing for Artsy, reminds us of Höch’s historical importance and legacy:

“In the digital age, Höch’s photomontages could seem quaint, but they’ve found their place among a significant artistic lineage that extends far beyond Dada. American artist Martha Rosler’s own photomontages from the 1960s, ’70s, and the 2000s,which contrast war imagery with domestic settings, share a kinship with Höch’s work. Höch’s many juxtapositions of women’s legs with objects and artworks seem like an obvious forerunner to some of photographer Laurie Simmons’s most famous works. Long before The Pictures Generation adopted a program of appropriating mass-media imagery, Höch had discovered the radical freedom of a cut-and-paste aesthetic—especially in a society trying to hold her back.”

More about her life and artwork can be enjoyed here.