The next Artist You Need To Know is Jack Shadbolt (1909 – 1998).

Shadbolt was a painter who was one of the most significant Canadian artists of the post World War II era : he was important both for his abstracted and expressionistic works but also as a teacher. He’s considered part of the second generation of modernists in British Columbia specifically and Canada on a larger scale who was strongly influenced by artists like Emily Carr and Frederick Varley while taking their inspiration and ideas even further artistically.

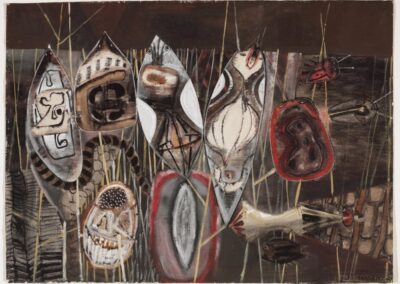

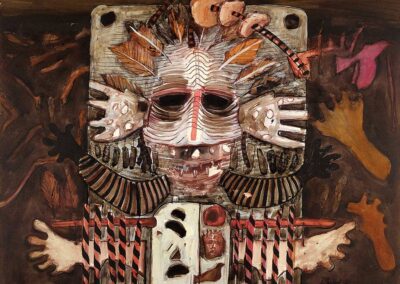

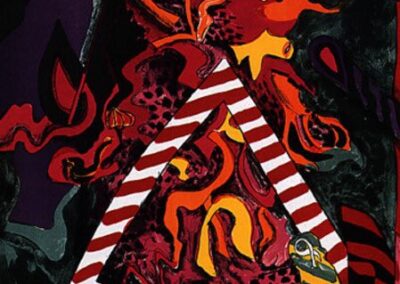

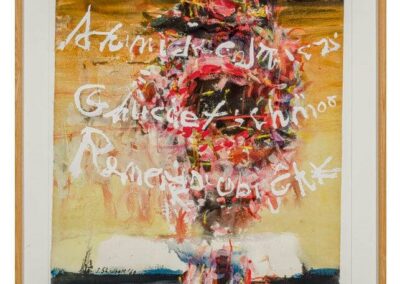

He was one of Canada’s most important artists of his era. Shadbolt’s paintings – and he produced many murals as well – often mined his personal experiences but also touched upon larger social and political conflicts in British Columbia (where he was based for most of his life and career) and global issues (First Nations, the Second World War, and the environmental movement).

“An artist is no bigger than the size of his mind.”

Shadbolt was born in the UK but his parents emigrated to Canada in 1911 : he grew up in Victoria, BC. His education was anything but provincial, however, as he studied in London (1937), Paris (1938) and attended the Art Students’ League in New York City in the late 1940s. But since the late 1930s Shadbolt had been teaching at the Vancouver School of Art, as well.

With the outbreak of WW II, Shadbolt enlisted and became involved as an administrator with the Canadian War Art Program when he was transferred to London. Many of these works are very different from his abstracted works but have a power and importance that echoes previous Canadian war artists and Shadbolt helped to set the parameters of this program that many future artists would also define in their own ways (such a previously featured AYNTK Joanne Tod).

Post WW II, Shadbolt resumed his faculty position at the ancouver School of Art (VSA) : he would teach there for another two decades, retirin gas the head of painting an drawing. His artistic output only increased after he retired,

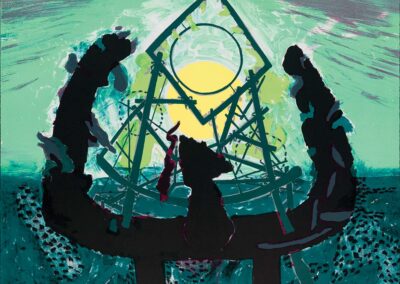

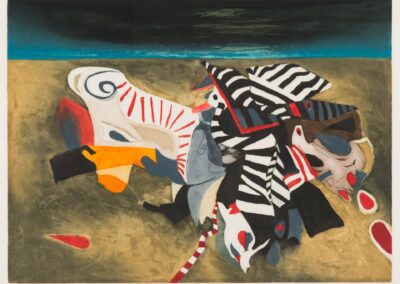

The words of Robert Linsley : “It has become a critical commonplace that Shadbolt’s work is constructed around a moving dialectic of opposites. Individual pieces are routinely described as an achieved balance of opposing forces – tight compositional structure versus disruptive energy. He himself has explained his working process in terms of a struggle between the demands of form and emotion.”

Jack and Doris Shadbolt would found (in 1987) the Vancouver Institute for the Visual Arts, a charitable foundation to provide grants to individuals in support of their artistic endeavours. The foundation was later renamed The Jack and Doris Shadbolt Foundation for the Visual Arts.

From art historian Scott Watson :

“Shadbolt’s history as an artist is tied to British Columbia. Something of the place’s repressed, violent colonial history erupts forth in his work. His lifelong search for form and his concern about its inherent instability are both a reflection of his involvement with the guiding existential metaphor of modernism and an allegory about the deep interrelationship between place and identity.

———————————

Shadbolt’s nature, on the other hand, is a vortex, a maelstrom opening onto the forces of darkness and chaos. He guarantees the continuity between this “nature” and society by seeing in it a mirror of the modern soul. Through the powerful synthesizing forces of abstract art, all cultures and times can be transformed by Shadbolt into the idiom given by local nature. But in Shadbolt, this program is disrupted and destabilized. It never returns us to the pastoral paradigm but alerts us to the fact that landscape—the genre in which we look for reassurance that we are somewhere familiar—is not yet home but a dangerously fragmented terrain. His insertion of figurative elements into the landscape, or conversely his flooding of figurativeness with landscape elements, has created a unique abstract genre. Some critics find that his works provide scant solace that the two can be harmonized. Instead, he seems to record forms as they splinter each other. This vision is sometimes apocalyptic, as if Shadbolt saw not just a present crisis but its horrible aftermath—though he is not a pessimist. Art itself is a kind of proof that the crisis can be borne, even if its resolution is far from sight.”

His artwork can be found in many galleries and museums across Canada (including the Vancouver Art Gallery, Burnaby Art Gallery, Musée des beaux arts (Montreal), the Edmonton Art Gallery, the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria and the National Gallery of Canada) as well as numerous corporate and private collections.

Shadbolt’s many awards include the Order of Canada (1972). A more detailed listing of his exhibitions and accomplishments can be seen here.

Much more about his life and work can be enjoyed here.