Our next Artist You Need To Know is Jeff Thomas.

Governor General Award winner Jeff Thomas is a photographer, curator, and cultural theorist. Self identifying as Urban-Iroquois, Thomas’ photographic practice re-contextualizes historical images of Indigenous Peoples within a contemporary landscape that speaks historically, culturally and geographically. He is an enrolled member of the Six Nations Reserve.

Thomas is as skilled with words as with his lens: “While studying 19th century photographs of indigenous people by white photographers I wondered what those indigenous people would have photographed if they had held the camera. What would the world have looked like seen through their eyes? This question was my point of departure as I began photographing the world around me.”

Further: “My research of photographic history pointed out two significant absences that would become the point of departure: The first was photographs depicting aboriginal people living in cities and the absence of images produced by aboriginal people. I was frustrated by the silence and challenged to stimulate conversations that did not exist.” (from here)

Thomas was born in Buffalo, New York and obtained an American Studies degree at the University of New York in Buffalo, while pursuing photography as an aside: but his life changed radically after a serious car accident in 1979, as the necessary convalescence and need to care for himself regarding the physical aftermath of the accident offered an opportunity to become a photographer with the “goal of weaving a new story from the fragmented cultural elements left in the wake of North American colonialism.” (from here)

“When I started working as a photographer that was the idea that I had in mind – to tell my own story. It was define myself as I saw myself which was as an urban based Iroquoian person. I remember looking for a definition of that, and I couldn”t find any and there are a lot of reasons why there wasn”t one. What I realized along with the absence of first nation practitioners from the past, was also this void of looking at the urban landscape through aboriginal eyes and what would that look like, what would an aboriginal photographer do, what would he photograph?”

The images below are from the series Scouting for Indians and Strong Hearts Portraits.

Thomas moved from Buffalo to Toronto in 1984 where he found a community with NIIPA (Native Indian/Inuit Photographers” Association). Speaking of his early experiences, in 2009, Thomas stated that “[it] was interesting because there was just sort of that new movement in defining ourselves and talking and just realizing that we weren’t alone and what does this all mean?”

In 1986 Thomas relocated to Winnipeg, MB and later would move to Ottawa in 1992. In Ottawa, he worked for the National Archives of Canada: this last move was motivated in part to expand his research into how Indigenous Peoples were represented – or misrepresented – in official Canadian documents. One of Thomas’ primary achievements in this sphere was “developing appropriate captions to replace dated terminology used to describe their collections of photos of Indigenous Peoples.” Another significant project was in 1996 when Thomas co-curated (with Edward Tompkins) the exhibition Aboriginal Portraits from the National Archives of Canada.

The images below are from The Champlain Series.

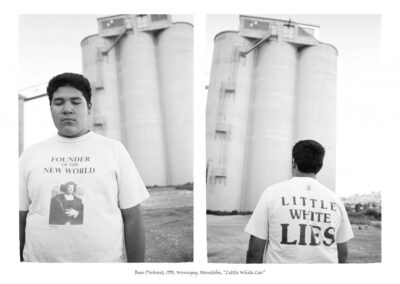

Thomas is perhaps best known for his works with his son Ehren “Bear Witness” Thomas from the time the latter was a child. From the National Gallery of Canada: “It was also during this time that Thomas took a snap shot of his son, Bear, that would change the direction of his practice….It was only after developing the image that Thomas realized its strength. It was as if the image forced the viewer to compare the stereotypical depiction of Indigenous Peoples, as seen on Bear”s hat, with that of his son, a young urban Indigenous boy. The graffiti on the wall acts almost as a call to action.”

The images below are from the Postcards For Indians series.

These ‘portraits’ of his son would be a major facet of Thomas’ work into the 1990s: but he would also create photographs with miniature Indigenous figurines and a number of later series where Thomas ‘documented’ – and encouraged photographic interventions with – monuments, office facades and government buildings in a visual critique and challenge of many stereotypical representations of Indigenous Peoples at those locales.

The images below are from the Corn Husks series.

Thomas was the subject of a documentary film by Ali Kazimi (an accomplished filmmaker, author and artist and recipient of the Governor General’s Award in Media and Visual Arts in 2019) entitled Shooting Indians (1997). In 1998, Thomas was awarded the Canada Council for the Arts’ “Duke & Duchess of York Prize in Photography” and in 2003 he became a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Art.

Significant exhibitions of Jeff Thomas’ work include A Necessary Fiction: My Conversation with Nicholas de Grandmaison, Where Are The Children? Healing the Legacy of Residential Schools, Landslide | Possible Futures, Mapping Iroquoia: Cold City Frieze, A Study of Indianness, Resistance is [Not] Futile, Father’s Day, and Emergence from the Shadow: First Peoples’ Photographic Perspectives (where Thomas also curated work from six contemporary First Peoples artists).

“My elders taught me to be proud of being Iroquois, inspiring me with their stories and their caution to never forget where I cam from. It was my challenge and I was determined to ensure that the description “urban Iroquois” could not be used as a derogatory assessment of my Indian-ness.”

Much more of Jeff Thomas’ work can be seen here as he has produced many bodies of work that overlap, and his accompanying texts you can find at this site offer a deeper understanding of his artwork and ideas. A more detailed – and impressive – accounting of his many exhibitions, publications and critical writings can be found here.