Our next Artist You Need To Know is Joseph Cornell (1903 – 1972).

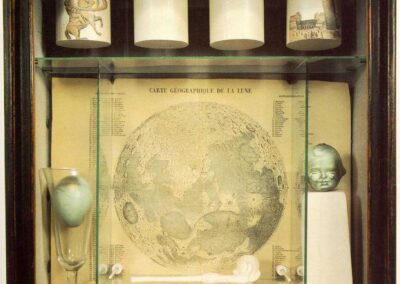

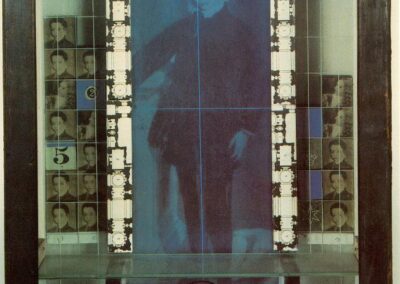

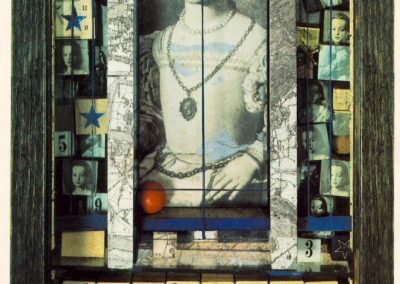

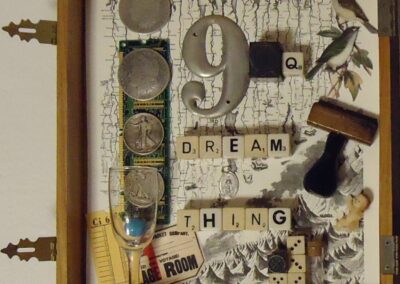

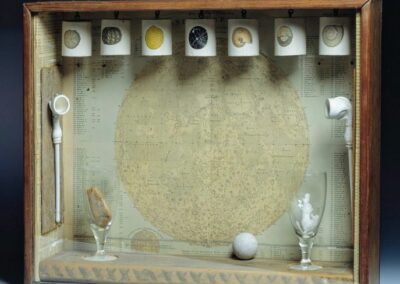

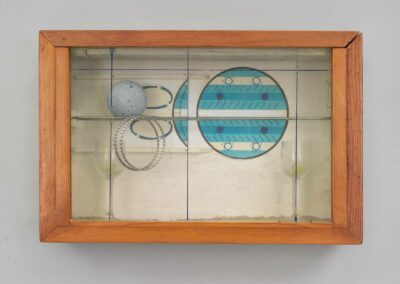

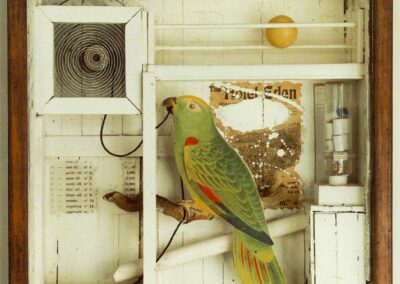

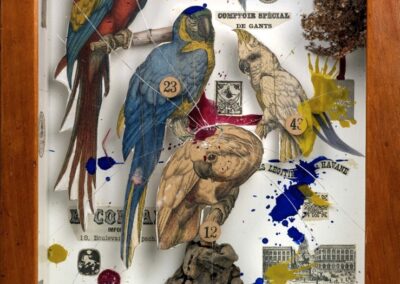

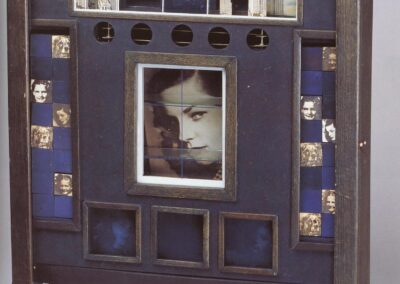

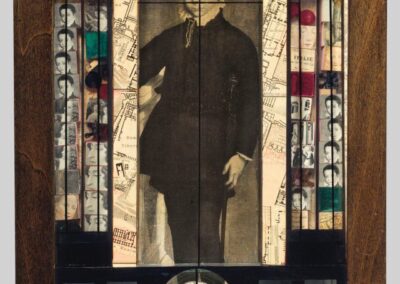

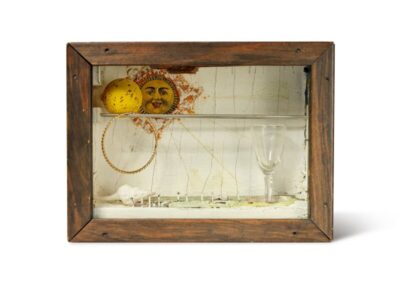

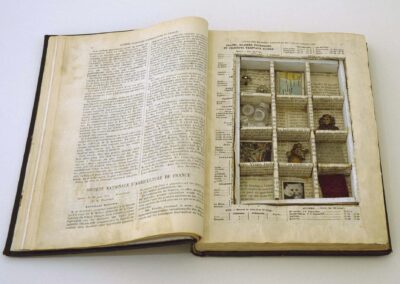

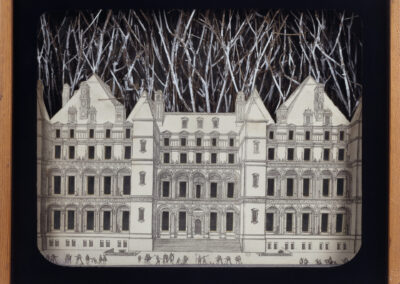

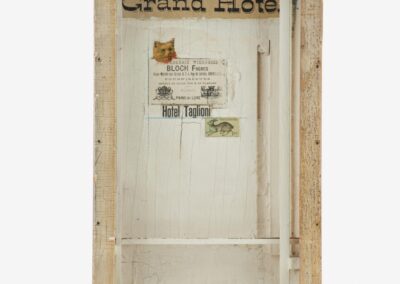

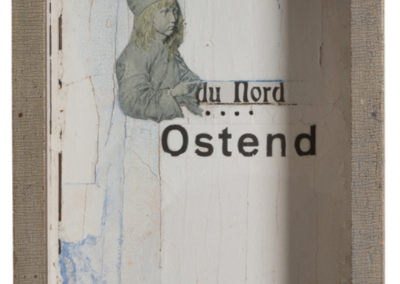

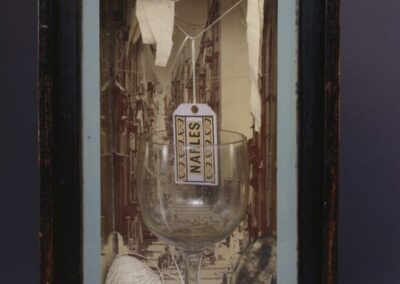

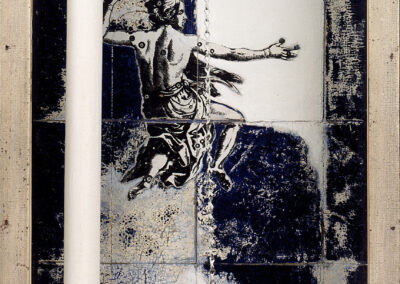

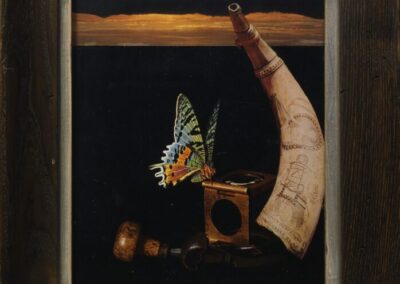

Cornell was an American visual artist and filmmaker : his pioneering work in assemblage set a standard for many artists who followed him. Primarily self taught – and living in isolation for most of his life and career as the caregiver for his mother and disabled brother – Cornell also experimented in avant – garde film, being influenced by the Surrealist art movement. Cornell’s three dimensional works employed found, discarded and sometimes created components. Though somewhat hermetic in his day to day life (which can be seen in the domestic nature of his boxes that suggest family artifacts or have an heirloom quality to them, like a family treasure box), Cornell was well informed and familiar with many of the contemporary art movements of his time.

“Cornell’s genius and originality disarm critics and make them affectionate and inspired […] It’s “that desperation of trying to give shape to obsessions,” as Cornell himself wisely wrote in a diary entry of no date.” (Charles Simic)

The above quote is from the 1992 book Dime Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell by Pulitzer Prize winning poet Charles Simic. This collection of poems and prose responds to individual works by Cornell but also the artist’s larger aesthetic.

Cornell was born in Nyack, New York and both of his parents were of Dutch ancestry and from prominent families in that community. However, his father died in 1917 and this was a serious blow to the family : this resulted in their relocation to the borough of Queens in NYC. He never attended any form or art school and except for a brief period (less than four years, when Cornell was at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, without graduating), he spent the majority of his life in a small house in Flushing – Bayside, NY in a ‘working class’ area.

Cornell cared for his mother and his brother Robert who had cerebral palsy, often working as a salesman going door to door in lower Manhattan : “Walking around the city and killing time between appointments, Cornell foraged in used bookstores and junk shops. He started collecting books, records, photographs, prints, theatrical memorabilia, and collected prints of old movies. He went to art galleries during the day and to the opera and ballet at night….In 1929 the family purchased the small frame house in Bayside. In the basement of that house, where Cornell lived till his death, he made all his art.” (from Simic’s aforementioned book)

But : “because Cornell was a self-taught, religious and private figure who kept his distance from the art world, an image has built up of a figure who was shy and eccentric, a naïve outsider artist [but] from the 1940s to his death he was involved in the New York and global art scenes.” (from here)

Beginning in the 1930s, Cornell interacted with many artists and writers from the Surrealist movement. He frequented the Julien Levy Gallery in New York (experiencing the artworks of Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp and Kurt Schwitters) and this helped shape his own aesthetic as well.

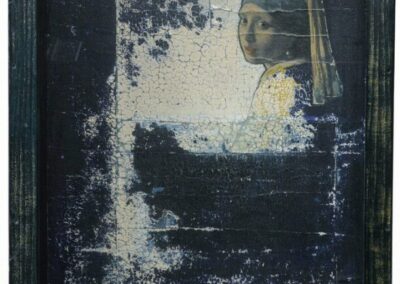

The important exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism (at the Museum of Modern Art in 1936) included work from Cornell. Cornell would mount his first two major solo exhibitions at the aforementioned Levy Gallery (1932 and 1939, respectively) : over the next few decades he was prolific, creating many of the ‘shadow boxes’ and assemblages for which he is best known. By the early 1960s, however, Cornell shifted his focus to more ‘flat’ collage and sometimes ‘reworking’ older assemblages. The final years of his life were marked by three major retrospectives of his artwork : one at the Pasadena Art Museum, another at the Solomon R. Guggenheim (both in 1967) and one focused on his collages at the Metropolitan Museum of New York (1970).

Considering the influence of film and popular culture on his shadow boxes and assemblage artwork, Cornell was also fascinated with cinema and produced a number of short films and experimental moving works. Important works in this genre from Cornell include Rose Hobart (ca. 1936) and Monsieur Phot (1933). The latter was included in Julien Levy’s book Surrealism (published in 1936).

A number of Cornell’s experimental films can be seen here and a listing of his filmography can be found here.

Cornell kept notebooks and many of his writings offer insight into his own creative process as well as his interior world. One of the more evocative assertions he made was that “collage = reality.”

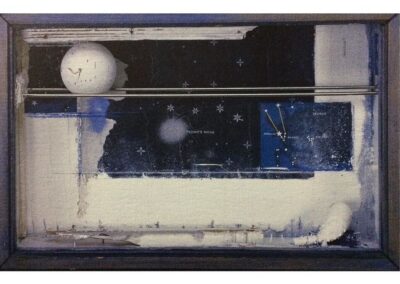

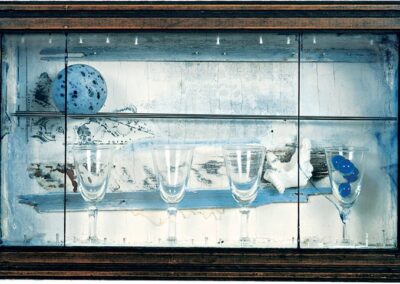

“Shadow boxes become poetic theater or settings wherein are metamorphosed the elements of a childhood pastime. The fragile, shimmering globules become the shimmering but more enduring planets—a connotation of moon and tides—the association of water less subtle, as when driftwood pieces make up a proscenium to set off the dazzling white of sea foam and billowy cloud crystallized in a pipe of fancy.”

“Beauty should be shared for it enhances our joys. To explore its mystery is to venture towards the sublime.”

From The Art Story : “Cornell’s influence on postwar American art was immense and varied. His shadow boxes constituted some of the earliest examples of assemblage and later helped inspire both Installation art and the box assemblage works of the Fluxus movement. Cornell’s use of preexisting artworks and the visual imagery of popular culture made his work an important forerunner of appropriation art and Pop art, inspiring such as artists as Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg. Cornell also made a major contribution to the development of cinema; he was described by the film critic J. Hoberman as a “progenitor of American avant-garde film.””

Joseph Cornell died in late 1972 : he had just turned 69 and the cause is believed to be heart failure. After his death the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation was formed “which administers the copyrights of Cornell’s works and represents the interests of his heirs.” Cornell’s relationship with his brother was very close (Robert had predeceased Joseph by seven years) and the artist had been very clear that the foundation was to honour his brother, as well as Cornell’s own legacy.

His artworks can be found in numerous collections including Museum of Modern Art (New York), Guggenheim Museum, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Tate Museum (London, UK), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC) and the Dallas Museum of Art.

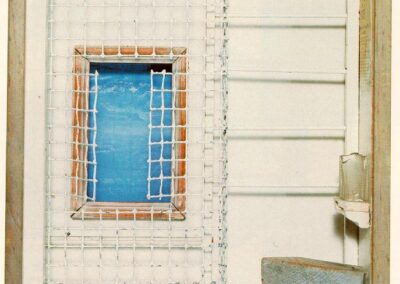

“Infinity: Time that has no story to tell.

You have the feeling that you are measuring the All with your own small piece of string. Perhaps the torn end of a shoelace?

That is why Cornell’s final boxes are nearly empty.”

(Charles Simic, Hotel at the End of the World from Dime Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell)

Again, from Simic’s book Dime Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell :

“You don’t make art, you find it. You accept everything as its material. Schwitters collected scraps of conversation, newspaper cuttings for his poems. Eliot’s Waste Land is collage and so are Pound’s Cantos.

The collage technique, that art of reassembling fragments of preexisting images in such a way as to form a new image, is the most important innovation in the art of this century. Found objects, chance creations, ready-mades (mass-produced items promoted into art objects) abolish the separation between art and life. The commonplace is miraculous if rightly seen, if recognized.

“The question is not what you look at, but what you see,” Thoreau writes in his journal. Cornell speaks of “being plunged into [a] world of complete happiness in which every triviality becomes imbued with a significance . . .”’

More about Joseph Cornell’s life and unique artworks can be enjoyed here.