Our next Artist You Need To Know is Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun.

He is one of the most outspoken and important – both in terms of his artwork and activism – contemporary Indigenous artists in Canada.

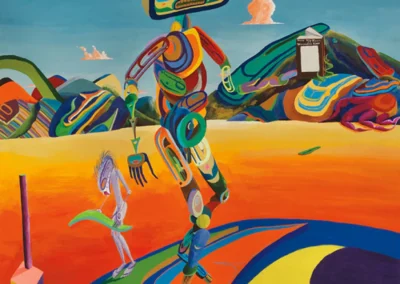

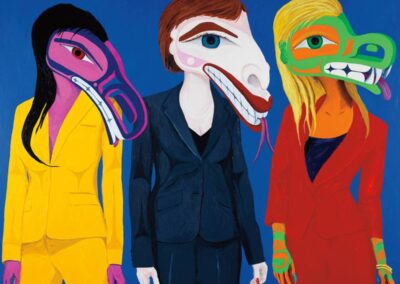

Yuxweluptun is of Cowichan / Syilx First Nations heritage. He graduated from the Emily Carr School of Art and Design in 1983, earning an honours degree in painting. Yuxweluptun’s “strategy is to document and promote change in contemporary Indigenous history in large-scale paintings using Coast Salish cosmology, Northwest Coast formal design elements, and the Western landscape tradition. His painted works explore political, environmental, and cultural issues. His personal and socio-political experiences enhance this practice of documentation.” (from here)

Although best known as a painter, Yuxweluptun has also worked in virtual reality and performance (such as his seminal work An Indian Act Shooting the Indian Act, 1997).

He is also very erudite, and his words are as striking as his artworks: “I’m a survivor and I will freely emancipate myself as a thinking person and I will walk in my traditional territory and I will talk to this world and some time, at some point, things will change.”

Christina Ritchie, responding to Yuxweluptun’s work in an article in Canadian Art Magazine in 2014, offers the following exchange about his ideas and aesthetic: “It has been said that Yuxweluptun uses the entire Canadian landscape tradition as an archive from which to construct a counter-narrative to the familiar one that links psychic possession of the landscape with the construction of a national identity propagated by the Group of Seven, though in a more general sense he takes issue with the popular myth that Canada was carved out of the wilderness. In Yuxweluptun’s world, the land is never unseen or unlived in. To make it so means dispossession for his people. Unlike Group of Seven works, his landscapes are always populated with figures who are usually engaged in activities that express their relationship to the land. “We have a saying,” he jokes, “that nothing is ever found until a white man names it.” The bitter punchline: “But it was never lost to us.” One history to which his paintings bear witness, then, is the dark and pathological underside of national identity.”

Both of Yuxweluptun’s parents were active in terms of Indigenous rights which was instrumental in shaping his own political positioning and artworks : “Yuxweluptun has said that while his father trained as a shaman and became a politician, Yuxweluptun himself was trained as a politician and became an artist.” (from here)

Yuxweluptun has had more than 25 solo exhibitions. Significant among these are Indian World (2013), Neo-Totems (2016), Drawings (2017) and New Works (2018): all of these were at Macauley Fine Art in Vancouver. Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun: Unceded Territories was mounted at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia in 2016.

A number of other important exhibitions that Yuxweluptun has been featured in include: Shore, Forest, and Beyond: Work from the Audain Collection at the Vancouver Art Gallery (2012); Neo-Native Drawings and Other Works: Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (Contemporary Art Gallery of Vancouver, 2010); Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun: Colour Zone (Plug In ICA, Winnipeg, 2001), and Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun: Born to Live and Die on Your Colonialist Reservation (Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver, 1995). He has been the recipient of the Vancouver Institute for the Visual Arts Award (1998), a Fellowship at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art (2013) and an Honourary doctorate from Emily Carr University of Art and Design (2019).

A more extensive listing of his many accomplishments can be found here and a more detailed story of his life and experiences can be seen here.

In many ways, Yuxweluptun’s work is as much about history and contemporary social issues as it is about painting: his scenes are narratives, telling a story that is often intentionally ignored. “History is the story we tell ourselves about how the past explains our present, and the ways we tell it are shaped by contemporary needs,” writes poet and activist Aurora Levins Morales, a Jewish Puerto-Rican woman. “All historians have points of view. All of us use some process of selection by which we choose which stories we consider important and interesting . . . storytelling is not neutral.” (from Patty Krwec’s book Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our Future)

More of Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun’s work can be seen here and here.