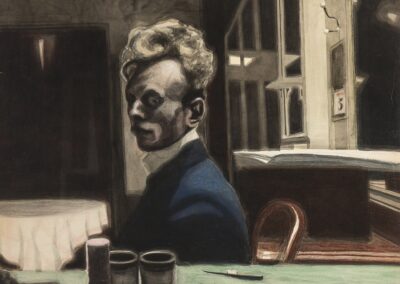

Our next Artist You Need To Know is Léon Spilliaert (1881 – 1946).

He was a Belgian Symbolist painter and graphic artist, best known for his haunting and haunted landscapes and self portraits. Spilliaert was born in the coastal town of Ostend but moved to Brussels at the age of 20 : he would live and work between the two cities for the rest of his life, though Ostend was often the subject – literally or symbolically – of his art.

Primarily self-taught, Spilliaert developed a unique style while still being of his time (his work can been seen within the Northern European canon of the time, with James Ensor or Edvard Munch), his ideas and artworks were also deeply influenced by his interest in the writings of Edgar Allan Poe and Friedrich Nietzsche.

“The streets and promenades of Ostend feel as if they are spread out against the sea and sky, to paraphrase T.S. Eliot, like a patient etherised upon a table. Spilliaert sought to escape their soporific, stifling influence by tramping them at night, in the bleakest of conditions. And by traversing the endless, elemental beach on foot. “I worked shut up at home all day,” he remarked of his twenties, a formative period in his development as a self-taught artist. “When it grew dark, I went out regardless of the weather, taking long walks for hours along the sea or cross country.” Painful stomach ulcers prevented him from sleeping and made Spilliaert a chronic insomniac. Like Munch [to whom he is often compared], in fact.

Spilliaert’s landscapes, seascapes and self-portraits from the 1900s – testaments of these lonely, relentless nightwalks – are experiments in the hallucinatory effects of physical exhaustion and psychological isolation. His laboratory is the silent, empty beach at night. Look, for example, at Beach Hut (1902). If photographs of Ostend at the turn of the last century celebrate the bustling sociability of the beach, then this drawing on paper is by contrast sinister in its blankness. Its single, isolated hut, a mysterious moonlit box, floats at the bottom left of the composition as if it has been abandoned by a receding tide.” (Matthew Beaumont, from the Royal Academy of the Arts)

He was born in Ostend, the oldest of seven children : from an early age, he was a “prolific doodler and autodidact”, drawing constantly. Spilliaert was often ill as a child, and has been described as “sickly and reclusive [spending] most of his youth sketching scenes of ordinary life and the Belgian countryside.” When he was 18, Spilliaert began a degree at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bruges : he never completed it, and most accounts cite his poor physical health as the reason. Spilliaert did attend the World’s Fair in Paris in 1900 with his father, who purchased a variety of pastels and other art materials there for his son, and which he would use as a primary media for the rest of his life. At this time he also experienced the work of Georges Seurat : the quiet, deliberate nature of Seurat’s pointillist paintings also helped shaped Spilliaert’s development as an artist.

In 1902, Spilliaert went to work in Brussels for Edmond Deman, who ran a bookstore and was an art publisher of the works of Symbolist writers, which Spilliaert was commissioned to illustrate. His interest in Edgar Allan Poe‘s work and other artists and writers of the Symbolist movement – and their influence upon his own artwork – can be marked from this period. A tenet of Symbolist art was that “dream and emotion could be reflected in landscape” (from the BBC) and this can be seen in many of his works.

Spilliaert’s worked almost exclusively in watercolor, gouache, pastel, and charcoal, mixing these media together in a style that was both simple but evocative in mood and tone, whether in his numerous self portraits or his many haunted, lonely landscapes : “frequently depicting a lone figure in a dreamlike space, Spilliaert’s paintings convey a sense of melancholy and silence.” (from here)

Spilliaerts’s isolated figures, alone in a landscape that often dwarfs them, were as much self portraits as his more traditional renderings of himself. These “lonely figures reflect his own isolation, tinged with a longing for something that is not yet present, there is an ongoing sense of life happening elsewhere.

The sadness is prevalent, as Spilliaert uses his internal landscape as a reference for various seascapes and portraits; in his own words, Spilliaert wrote. “I’m tired of waiting for luck to come my way, in the end that leads to abjection.”” (from here)

From a letter the artist wrote in 1920, speaking of Ostend, which both inspired and defined his aesthetic and life : “I belong here so much. I am living in a real phantasmagoria… all around me dreams and mirages.”

Léon Spilliaert died on 23 November 1946 in Brussels. A statue has been erected, in his honour, titled Hommage to Léon Spilliaert. It’s installed (appropriately) in Ostend and is inspired by his painting Vertigo. He was also made a Knight of The Order of the Crown in 1922, one of Belgium’s highest honours.

From the BBC : “Léon Spilliaert’s eerie, enigmatic works inhabit a twilight netherworld between reality and dream. It was a realm he conjured following the moonlight strolls he took to calm his insomnia-induced restlessness. In the dead of night he would ponder the philosophical issues that preoccupied him: the creation of the world, relations between the sexes, and the ultimate fate of man. His thoughts would be transformed into ghostly portrayals of his hometown of Ostend, still-lifes in which objects have a mysterious life of their own, and a series of extraordinary self-portraits in which the Belgian artist bored deep into his own soul.”

More of his work can be seen here. A short video offering a tour of an exhibition of his works with the Royal Academy of Arts can be enjoyed here.

Irish composer Ian Wilson’s Spilliaert’s Beach (for violin and piano) is both inspired and a tribute to Spilliaert’s painting Beach in Moonlight, Seascape with Light (1908) : that can be enjoyed here and offers a fine soundtrack as you view the artist’s work.