Our next Artist You Need To Know is María Sol Escobar (1930 – 2016) who was perhaps better known as simply Marisol.

She was a Venezuelan -American sculptor born in Paris, who lived and worked in New York City. Marisol became internationally known in the mid 1960s (even having an artwork featured on the cover of TIME Magazine) but would eschew the larger art world after a little more than a decade of ‘fame’, before being appropriately recognized decades later as a groundbreaking, and evocatively difficult to classify, sculptor and assemblage artist.

As she preferred to use solely Marisol during her career, and that’s how she’s known, we’ll be referring to her in that manner through this essay.

“I don’t think much myself,” she told the critic Brian O’Doherty in The Times in 1964. “When I don’t think, all sorts of things come to me.”

Marisol’s art education was “irregular, eclectic and self – taught” : she did study at the Beaux-Arts in Paris (1949) and the Arts Student League in New York (1950) after she relocated to the United States. She was part of the Hans Hofman School from 1951 to 1954, which was in Greenwich Village amidst the burgeoning Beat Generation cultural scene.

Marisol was born in Paris in 1930 : her parents were wealthy Venezuelans and they frequently travelled around Europe. As the decade progressed, they generally lived in Caracas and the United States. Marisol, when growing up, read “American comics and Italian fumetti and drew pictures of the saints she learned about in Catholic school. Her mother committed suicide in 1941 and Marisol, who toggled between schools in New York and Caracas, stopped speaking. ‘I didn’t want to sound the way other people did,’ she later explained. ‘I didn’t really talk for years except for what was absolutely necessary in school and in the street […] I was in my late 20s before I started talking again.’” (from Apollo Magazine) This reticence regarding language would continue throughout her life.

More from Apollo : “In 1946, she moved with her father and older brother to Los Angeles and María Sol became Marisol, a nickname given to her by her mother and a portmanteau of the Spanish words for ‘sea’ and ‘sun’. Her early art training was a hodgepodge of night studies at the Otis Art Institute and the Jepson Art Institute in LA, painting lessons at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and classes in painting, sculpture and ceramics at a host of New York schools and with individual instructors, including Hans Hofmann [she studied with him from 1951 to 1954 at his school, which was in Greenwich Village amidst the burgeoning Beat Generation cultural scene]. She had come to New York on her own, traveling across the country by bus in 1950.”

When she moved to NYC, she used the singular name Marisol in her work and career : this is fitting as “it would be in New York City that the artist found her home and purpose. From 1950 onward, stars aligned for Escobar as she navigated the art world of her moment: a tutelage under Abstract Expressionist master Hans Hofmann; nights at the Cedar Tavern that introduced her to art stars like Willem de Kooning; and a fruitful friendship with Andy Warhol. She even appeared in two of his films from the 1960s, including The Kiss, and the Screen Test 13 Most Beautiful Women.” (from artnet)

She was not easily pigeonholed in terms of her artwork : Marisol’s exploration and interest in pre-Columbian artifacts was a unique aspect of her artwork that clearly delineated her from the many art movements at play in NYC at that time, and especially the Pop Art milieu of the early 1960s that she was often included within. In her characteristically insightful and forthright manner, in an interview in 1968 for the Archives of American Art, when asked if she “identified as a pop artist…the artist carefully mused, “maybe its better not to.”” (from here)

Marisol began to focus exclusively on sculptural installations in 1951, and her works are immediately recognizable. Perhaps her most well known work – and considered by many to be her opus – is The Cocktail Party (in 15 parts). A video of this work can be enjoyed here, as the figures and scene that Marisol created are an experience that can’t always be appropriately conveyed in an image. The images below are from Steve Zucker and the Toledo Museum of Art.

Marisol exhibited with the Castelli Gallery in New York and later at the well respected Stable Gallery in the 1960s, and in 1962 at the Venice Biennale. Other notable exhibitions : the Art of Assemblage exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (1961), a solo exhibition In 1967 at the Hanover Gallery (London, UK), and that same year she was featured in the exhibition American Sculpture of the Sixties. In 1968 she had an individual exhibition at the Boymans van Beuningen Museum (Rotterdam) and in 1969 Marisol was included in an exhibition of Pop Art at the Hayward Gallery. Other notable exhibitions from this period include shows at the Moore College of Art (Philadelphia, 1970), the Art Museum (Worcester, MA, 1971) and the Cultural Center (New York, 1973). Much later, in 1991, she had an exhibition focused upon her portrait sculptures at The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. (from here)

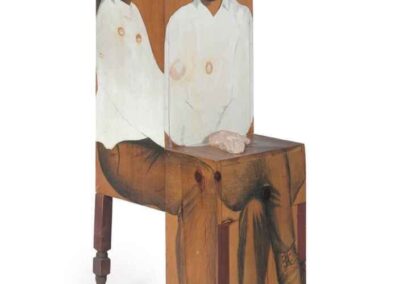

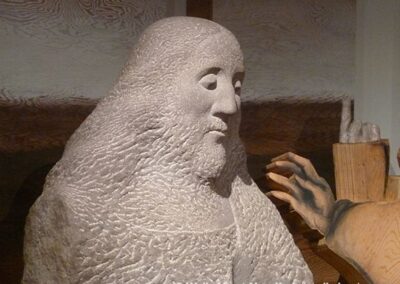

From AWARE : “Her reputation as a “party girl” in the magazines and the very nature of her name (Marisol, “sea and sun”) were instrumental in making her an icon. And yet, although her wide-ranging subjects were often inspired by the “trivial” aspects of life which brought fortune to Pop Art, the works she exhibited….stand out from the movement even more in that they contain a strong element of social satire. Her large groups of simple, rigidly shaped figures associate two and three-dimensional elements in novel ways. Working on mostly rectangular wood blocks, she carved out only a few body parts, such as the legs and heads with many faces…and painted the figures’ different profiles (face, side view, back). Only a few parts manage to pull through this flat frontality, at once reminiscent of medieval column statues, Native American totems, and Hofmann’s theories – the heads, glued, painted on or sculpted; and sometimes the hands, the sole signs of expression of these lifeless masks lined up next to each other in voluntary solitude. Thus extracted from the block, as if dissected, these elements (hands, breasts, heads) emphasise other objects, like ready-mades, found or made by the artist,…”

Her own words about her process from 1968 (and Marisol was famously taciturn with critics and interviewers) : “In the beginning I drew on a piece of wood because I was going to carve it. And then I noticed that I didn’t have to carve it, because it looked as if it was carved already.”

One might argue that her works, amidst the cacophony of Pop Art, offered nuances and contested narratives that required time and consideration for their importance to be fully appreciated. Her relationship to the larger art world was also something that she didn’t allow to define her, and at the height of her ‘fame’ she took a hiatus from that scene. From Hyperallergic : “While Marisol enjoyed her celebrity status she often chose to escape from the hustle of New York City. In the 1970s the artist left to travel the world, spending extended periods of time in Asia, Europe, and Latin America. Marisol’s journey abroad would change her perspective on the subject matter she’d been pursuing in her earlier work, especially in light of the dramatic events of the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War, among other important historical moments of the 1960s. When she returned to the US, she was poised to make a more poignant social critique.”

Like many female artists of her generation, Marisol was not awarded as much attention as other male artists. But there was a revival in interest in her work later in her life. The Museum of Modern Art In 2004 mounted a massive exhibit of her work, and ten years later, Marisol was honored with her first solo show in New York, at the Museo del Barrio. When an impressive retrospective of Marisol’s work was on view at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), assistant curator Maritza Lacayo pointed out that “She refused to adhere to social norms and the norms of the art world. But that is why she was rejected by the art historical canon. If you don’t place yourself, they will place you.”

Marisol passed away in New York City on April 30th, 2016 : she had been in poor health, afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease, and was 85 when she died from pneumonia. The next year, it was revealed that Marisol’s estate, in its entirety, had been bequeathed to the Buffalo AKG Art Museum (formerly known as the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York). Her artworks can also be found in the collections of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Currier Museum of Art, ICA Boston, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, and the Museum of Modern Art.

In an obituary in the New York Times offered the following on the occasion of her passing : “Marisol, who leaves no immediate survivors, might or might not have cared about the renewed attention [in the 2000s]. When asked in 1964 how she would like her work to be seen by critics and the public, she seemed puzzled by the question. “I don’t care what they think,” she said.”

Art historian Sara Garzon offers the following, in a fine obituary of Marisol : “Often with woman artists, their biographies take precedence over a true understanding of their work. Which is why I dedicate this short eulogy to Marisol’s aesthetic sensibility and critical engagement with the social and political issues of her time. Although Marisol may have been somewhat forgotten in recent years, her centrality in the art world during the 1960s and well into the ’80s is unquestionable, and cannot be considered anything less than a significant contribution to the history of art.”

More details about her life and career can be found here.