The next Artist You Need To Know is Oscar Cahén (1916 – 1956).

Cahén (sometimes spelled Oscar Cahen) was a Canadian painter and illustrator and is an interesting study in contradictions within an artist’s practice. He is, on the one hand, well known for being a member of Painters Eleven (one of the most significant groups of abstract artists in Canadian art history, whom were active in Toronto roughly between 1953 – 1960) but is also very familiar to many for his prolific work as an illustrator for Canadian magazines.

A previous editor of Canadian Art Magazine Donald W. Buchanan offered the following : “Cahén does not paint things as they are but as he is. He depicts not what he sees but feelings the subject provokes in him.”

Cahén was born in Copenhagen, Denmark but his family lived in several European countries as he was growing up: his father was a well known anti-Nazi activist and journalist. He would attend the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts for the period of March 1932 to August 1933 : his primary instructor was Max Frey but Otto Dix was also there, at that time.

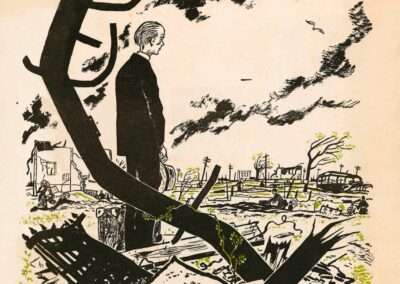

As WW II broke out, Cahén was working as an editorial illustrator for a number of magazines and had also begun painting, primarily in an abstract style that seemed to be in contrast to his commercial works.

He taught in Prague at the Rotter-Schule für Werbegrafik but with the Nazi invasion and occupation in 1939 he found himself in dangerous waters. His mother and father would seek refuge in England and the USA, respectively, and after harassment and persecution by the German Nazi forces, Cahén knew he had to do the same for his own safety.

Fleeing to England that same year, the British deemed him to be German and he was interned in a prisoner camp before being sent on to Canada as an ‘enemy alien’. This was a common policy for Europeans of Jewish descent, like Cahén, and his artistic and cultural contacts played a significant hand in securing his ‘release’ to Canada. He landed in Montréal in 1942 and immediately found work as an illustrator : Cahén would relocate to Toronto in 1944 and became the art editor for Magazine Digest.

Cahén has his first solo show in Copenhagen in the 1930’s when he was not even yet twenty (and had been exhibiting widely while still in Europe), and in Canada he quickly moved to forefront of Canadian painting. He was juried into the Annual Spring Show of the Ontario Society of Artists in 1947, and would show with many groups such as the Royal Canadian Academy, the Canadian Society of Painters in Watercolour and the Canadian Society of Graphic Art.

But the most significant – in terms of both Cahén’s own career trajectory but also in terms of abstraction in Canada – exhibition he participated in was Abstracts at Home (1953). Included in this show were the artists William Ronald, Jack Bush, Jock Macdonald and Alexandra Luke whom would all be part of Painters Eleven. This group would redefine Canadian art over their tenure of collective exhibitions and collaboration and their legacy is still felt today.

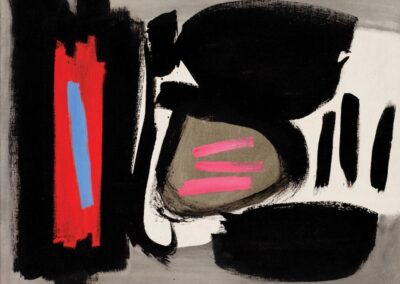

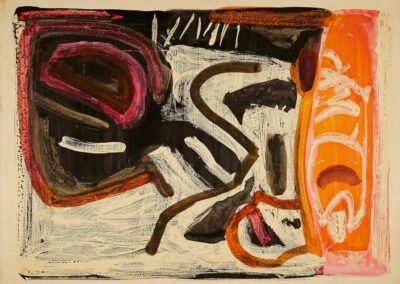

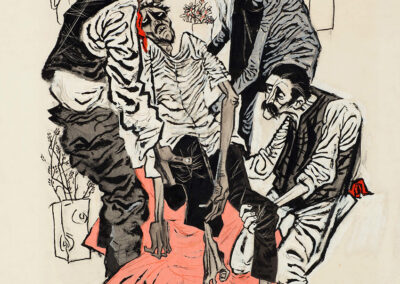

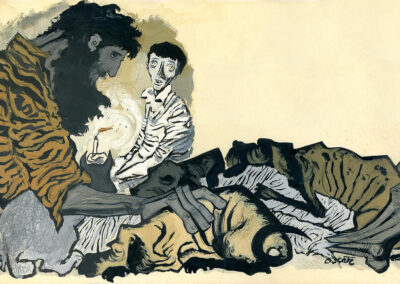

From here : “Some of Cahén’s earliest works are reminiscent of German religious and figurative expressionism, with dark and moody subjects. By the early 1950’s Cahén’s paintings developed a more formal structure with broader and stronger colours reflecting the artist’s interest in contemporary painting, and followed experimentation with cubism that would begin Cahén’s exploration of abstract forms. By 1954 Cahén’s work often featured monochromatic areas of fluid, organic forms that had lost all traces of cubism.”

From the Art Canada Institute : “Oscar Cahén did not theorize about painting very much, preferring instead to act instinctively. When asked what his abstract pictures meant, he retorted: “Why don’t you go out and ask a bird what his song means? I’m not interested in telling a story . . . when I paint, I set down the pushing and pulling of my emotions.” But his friend [and renowned artist] Harold Town (1924–1990) saw in Cahén’s work a “voracious appetite for living . . . [expressed in] joyous colour . . . [and] forms that suggest growth in exultant upward thrust . . . a sense of his deep concern with the life force.” This expression of surviving and thriving encapsulates not just Cahén’s life but also Canadians’ postwar energy and rapid economic and cultural development.”

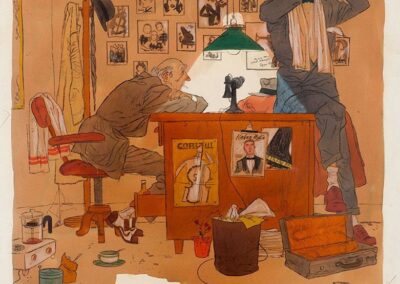

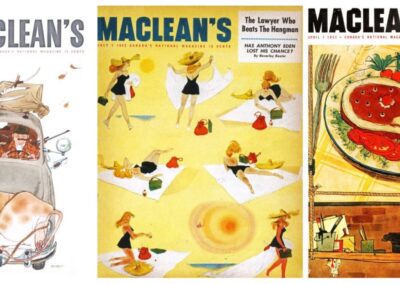

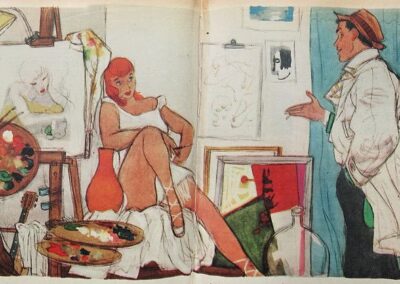

Concurrent to his fine art career, Cahén also produced many illustrations for magazines such as Maclean’s, Chatelaine and New Liberty. In this field, Cahén won five medals and six awards of merit from the Toronto Art Directors Club, 1949–1957. It’s not hyperbole to say that he was a major figure in terms of graphic and illustrative arts in Canada. His more commercial work in this area often supported his fine art practice and many people were ‘fans’ of Cahén’s lively and entertaining genre and everyday scenes whom might never be aware of his work in galleries.

A more comprehensive look at his illustration works can be seen here.

Impressively, in just a four year period (1953-1956), Cahén participated in 43 exhibitions : highlights include a solo show at Hart House (1954), and how in 1956 he was commissioned to produce a cycle of murals for the new landmark Imperial Oil building.

Cahén was killed in a car accident in Oakville, Ontario in 1956 and his unexpected and early death at just the age of 40 left a significant gap in both the fine art and illustrative spheres.

Posthumously, his friends and peers came together to present exhibitions of his work for another three years, culminating in a memorial solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto (what would later become the AGO Art Gallery of Ontario) in 1959. Two later retrospectives of Cahén’s art would be mounted at the Ringling Museum of Art (Sarasota, 1968) and the Art Gallery of Ontario (1983).

His work can be found in numerous collections including the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Art Windsor Essex, National Gallry of Canada, Royal Bank of Canada, Vancouver Art Gallery, Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and Museum London.

Much more about Cahén’s life and work can be seen here (he was the subject of a book by the Art Canada Institute) and here.