The next Artist You Need To Know is Philip Guston (1913 – 1980).

Philip Guston (born Phillip Goldstein) was a Canadian American artist primarily known for his paintings, but was also a printmaker and muralist. Over his career, he moved from social realism (though also inspired by Italian Renaissance artists) to abstract expressionism (Guston was a founding figure of the New York School in the mid twentieth century which centered NYC as the focal point of the international art world) and then to a more representational style that has been called neo-expressionism that still unsettles today – and his works from this period have been a contested point of debate for museums and the art world very recently, decades after his passing.

Pulitzer Prize winning critic Jerry Saltz has described Guston as being among the “most important, powerful, and influential American painters of the last 100 years”. Robert Hughes – one of the most important art critics of the 20th century (and often ideologically in opposition to the aforementioned Saltz) described Guston “as a figurative artist of extraordinary power.”

Guston’s words : “To paint is a possessing rather than a picturing.”

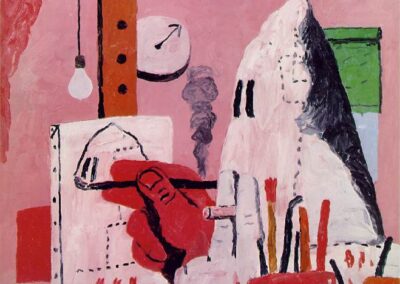

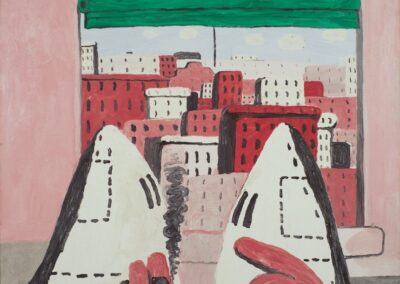

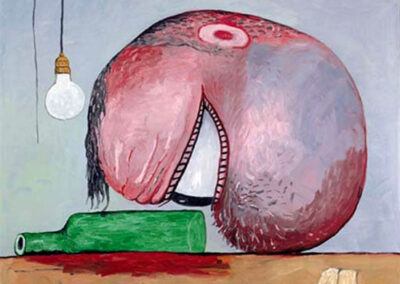

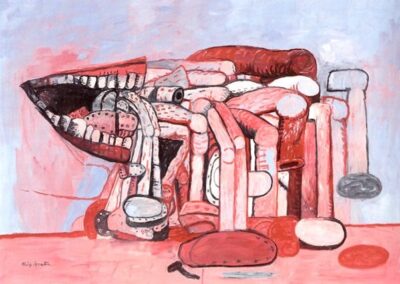

The gallery below offers a selection of Guston’s infamous Ku Klux Klan paintings.

In response to cancellations and other ‘concerns’ about exhibiting these works in 2020, Guston’s daughter Musa Mayer asserted the following : “Half a century ago, my father made a body of work that shocked the art world. Not only had he violated the canon of what a noted abstract artist should be painting at a time of particularly doctrinaire art criticism, but he dared to hold up a mirror to white America, exposing the banality of evil and the systemic racism we are still struggling to confront today.

In these paintings, cartoonish hooded figures evoke the Ku Klux Klan. They plan, they plot, they ride around in cars smoking cigars. We never see their acts of hatred. We never know what is in their minds. But it is clear that they are us. Our denial, our concealment.” (from The Guardian)

Guston – whose parents were Ukrainian Jews who fled Odessa to escape pogroms and persecution – was born in Montreal, but the family would relocate to Los Angeles in the United States in 1919. At this time, California – like many parts of the USA – was rife with Ku Klux Klan terrorism against a number of groups, and it’s suggested by some biographers that Guston’s father – who committed suicide – was perhaps driven to this by the Klan – and their official enablers – as the family lived in poverty for many of these years.

His art education was sporadic : an early interest in drawing was encouraged by his mother, and Guston was enrolled by her in a correspondence course from the Cleveland School of Cartooning as a child. At the Los Angeles Manual Arts High School he became friends with Jackson Pollock, and they would remain so for the rest of their lives. While there, one of Guston’s teachers was Frederick Schwankovsky: and he absorbed a great deal of art history and wider education in terms of European modern art, philosophy and other cultural subjects. Amusingly, Pollock and Guston were expelled over a paper they published there, decrying the school’s privileging of sports over art education.

Guston would earn a one year scholarship to the Otis Art Institute of Los Angeles : but he didn’t find this to his liking, and would never again return to educational spaces, being primarily a self-taught artist, whose style and ideas were informed by his own research.

Guston’s career acts as a mirror to a number of significant art movements in the United States over the tumultuous period spanning from pre WW II to the 1970s, striving from social realism to abstract expressionism to more narrative and again socially engaged works.

His very early work was political, including a number of mural works that owed a great deal in terms of intent and style to the work of Mexican artist David Siqueiros and were often met with resistance – and often outright defacement – by more right wing groups in the United States. More about this brief, but formative period can be seen here. It’s worth noting that the ‘hooded figure’ that would come to be a hallmark of Guston’s aesthetic first appeared at this time.

In the mid 1930s, Guston moved to New York City and began doing work with the WPA (Work Progress Administration) during the Great Depression (a number of other artists that would help define American – and global trends – in visual arts also cut their teeth in this program, including previously featured Artist You Need To Know Ad Reinhardt). Like many of the programs instituted by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, these were ways in which to spur economic development, in spaces such as public works but also in cultural spaces, such as the murals and other public art projects that artists like Guston worked upon.

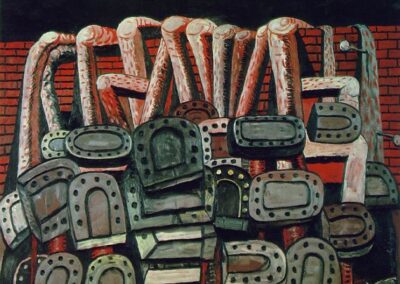

But in the 1950s Guston would shift his practice dramatically, becoming one of the major figures in the Abstract Expressionist movement in New York, though he preferred being described as being with the New York School. During this time, his works had an ethereal quality that was unique to his contemporaries. A founder of the aforementioned New York School, Guston’s paintings were at the forefront of American abstraction at this time, and he was featured in the Ninth Street Show as well as the journal of the avant garde titled It is. A Magazine for Abstract Art.

However, in 1967, Guston abandoned this entirely – going so far as to dismiss American abstract art as ‘a lie’ and ‘a sham’ – for the style that would truly define his practice, and begin to create the paintings that even nearly half a century after his death, can both challenge and confront viewers.

Below area selection of his abstract works that brought him recognition in the post WW II period.

Guston moved to Woodstock, in New York state, in 1967 and began to paint in a more representational style again that was also somewhat cartoonish. This was greeted with both praise and derision from his former artistic community. When Guston exhibited many of these works – including the infamous Klan paintings at the Marlborough Gallery in New York in 1970, the reviews were acerbic and dismissive (though some, like the previously cited Robert Hughes, would later change their minds, coming around to Guston’s own frustration with the often irrelevant and insular – considering the era they were all living within, in the United States, with racial and economic tensions). A notable dissenter to this affront at Guston’s shift in practice was the painter Willem de Kooning, whose own work often straddled – and dismissed – the pedantic critical expectations.

Guston continued to isolate himself from the NYC art world in Woodstock, as a response to what his daughter would describe as the art world and so many others (perhaps willfully) misunderstanding his art and ideas.

A quote from Guston from 1960 perhaps best exemplifies his motivations : “There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth we inherit from abstract art. That painting is autonomous, pure and for itself, therefore we habitually analyze its ingredients and define its limits. But painting is ‘impure’. It is the adjustment of ‘impurities’ which forces its continuity. We are image-makers and image-ridden.”

In this mature period, Guston “created a lexicon of images such as Klansmen, light bulbs, shoes, cigarettes and clocks” that would be recurring characters in the world he was creating, that was more and more a response to the world outside his studio instead of a more formal and bloodless continuation of abstraction.

Guston’s artworks can be found in many collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Detroit Institute of Arts, the High Museum of Art, the Honolulu Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, National Gallery of Art, Tate Modern and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. A more extensive listing can be seen here.

Despite his disinterest in institutions in terms of his own practice, Guston taught at several universities including New York University and the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn (1973 – 1978) : he also had an ongoing monthly graduate seminar at Boston University. Guston was also artist in residence at the School of Art and Art History at the University of Iowa (1941 to 1945) and the St. Louis School of Fine Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, in the late 1940s.

Guston was also elected to the National Academy of Design as an Associate Academician, posthumously.

“Painting and sculpture are very archaic forms. It’s the only thing left in our industrial society where an individual alone can make something with not just his own hands, but brains, imagination, heart, maybe.”

Guston passed away in Woodstock in 1980, at the age of 66 from a heart attack – not long a massive retrospective of his work opened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Guston’s obituary (in no less a space than The New York Times) can be read here.

Learn more about Philip Guston’s art and legacy here at The Art Story and a site dedicated to Guston’s artwork and legacy can be enjoyed here. A complete listing of his exhibitions can be found at this site as well as an extensive archive of his many artworks.