Our next Artist You Need To Know is more historical, but in this ongoing series we like to range into many different eras and arenas.

Rodolphe Töpffer (1799 – 1846) was a Swiss author, teacher, painter, cartoonist, and caricaturist: Töpffer illustrated books such as Histoire de monsieur Jabot (1833) Histoire de M. Vieux Bois (The Story of Mr. Wooden Head, 1837) and Histoire de Monsieur Cryptogame (1845). These are acknowledged as being among the earliest, if not the first, European comics and graphic novels. The comic strip, as we know it and recognize it today, is built upon Töpffer’s graphic artworks.

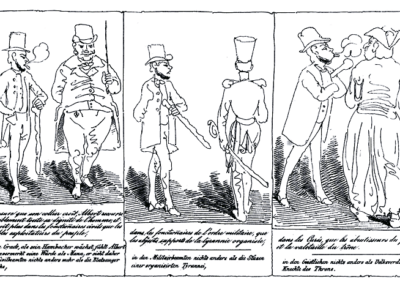

From here: “Töpffer’s prodigious originality is not only evident in the graphics; he also invented a number of concepts that are still part of the foundations of comics today. Not only does Töpffer invent, for example, the frame and the vignettes, but he varies their number and size according to the rhythm of the action.”

He was the son of the painter Wolfgang Töpffer (originally from Germany, but had emigrated to Geneva as he found it to be a freer space for art and criticiality): Wolfgang was a professional painter and occasional caricature artist, but his primary claim to historical significance “is serving from 1804 to 1807 as “Drawing Master” of Joséphine, Empress- consort of the First French Empire.”

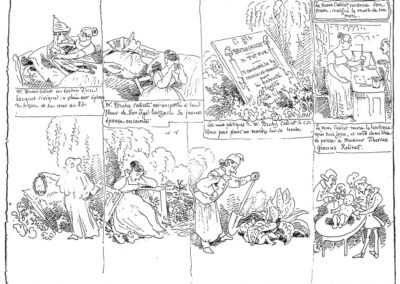

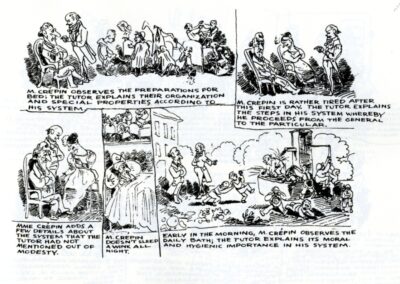

Töpffer lived in Paris, France from 1819 to 1820, but this was his only formal art education. Upon his return to Geneva he worked as a school teacher, and in 1823 he was able to establish his own boarding school for boys. Later, in 1832, Töpffer obtained the position of Professor of Literature at the University of Geneva. In many ways, this was his primary, chosen profession: but he would “gain his fame from the activities he pursued in his spare time. He depicted a number of local landscapes in paintings considered influenced by the contemporary movement of Romanticism. He became an author of short stories and occasionally entertained his students by drawing caricatures.” The previously mentioned Histoire de M. Vieux Bois (The story of Mr. Wooden Head) “consisted of 30 pages, each containing one to six drawn panels with a caption of narration below. It was translated and republished in the United States in 1842 as The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck. Töpffer’s stories were produced by autography, a variation of lithography that allowed him to draw on specially prepared paper with a pen. This process allowed for a loose line, quicker and freer than engraving, the usual process for printed illustration at the time.” (from here)

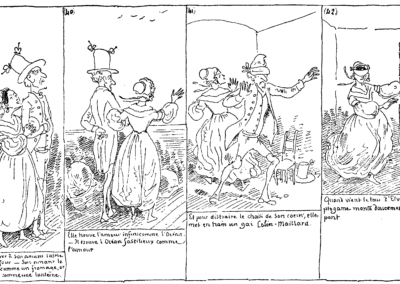

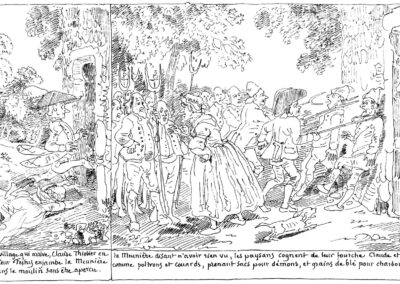

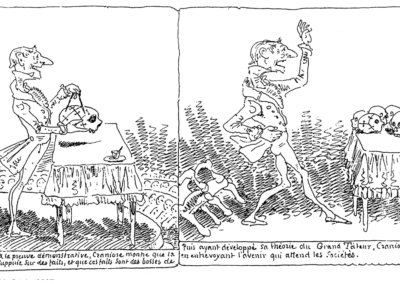

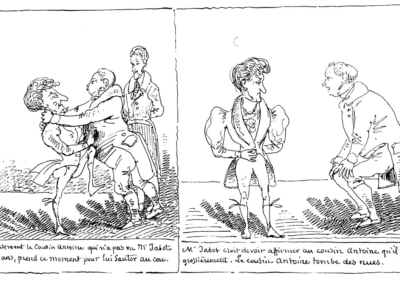

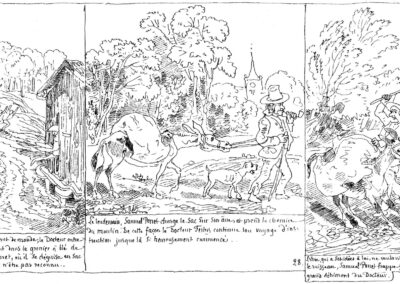

Töpffer’s stories are filled with “a species of absurdist antiheroes who struggled desperately, fruitlessly, and farcically against the caprices of fate, nature, and an irrational, mechanistic society. The stories (lithographed in little oblong albums containing up to 100 pages) are purposefully purposeless, flow with calculated non sequiturs, and make digression a narrative principle. The pace is sustained by another revolution in draftsmanship, for Töpffer discovered how to turn systematic doodling to account, how to exploit the accident, and how to vary physiognomies experimentally. By abandoning anatomical three-dimensional drawing, he showed how to render movement for movement’s sake. Töpffer’s strips are also morally mobile: in his work the normal relationship between cause and effect or crime and punishment, which had underpinned all the older stories, disintegrated. Töpffer’s satire was broadly based: he mocked social climbing, educational systems, parliamentary chaos, political scaremongering, scientific and medical pretensions, and revolutionary zeal, but his sense of fun and taste for the silly are always uppermost.” (from here)

For example, one of the more amusing vignette, from Histoire de M. Vieux Bois has the following text below the irreverent sketches: “Mr. Oldbuck, in despair, commits suicide. Fortunately the sword passes below his arm. For eight-and-forty hours he believes himself dead. He returns to life dying of hunger.”

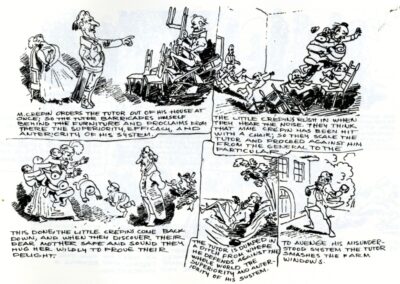

A brief overview of some of his publications is both informative and amusing, as an example of Topffer’s somewhat irreverent aesthetic. Histoire de M. Jabot chronicles the misadventures of “a middle class dandy who attempts to enter contemporary High Society.” Monsieur Crépin (1837) tells the story of a father, who in hiring a series of tutors for his children, finds himself lost in the teachers’ eccentricities. Monsieur Pencil depicts “an escalating series of events beginning with an artist losing his sketch to the blowing wind and almost resulting in a global war. Le Docteur Festus [is all about] a scientist [who] wanders the world, offering his assistance. He is blissfully unaware that disaster marks his path.”

Considering the playful immediacy of his work, Töpffer also wrote about children’s art and their creativity in his book Reflections et menus propos d’un peintre genevois (1848). Published posthumously, he asserted “that children often displayed greater creativity than trained artists, whose creativity was often overshadowed by their technical skill.” (from here)

Several of Rodolphe Töpffer’s books, or publications of his collected works, can be found online, including his illustrated novella My Uncle’s Library.