The next Artist You Need To Know is Kurt Schwitters (1887 – 1948).

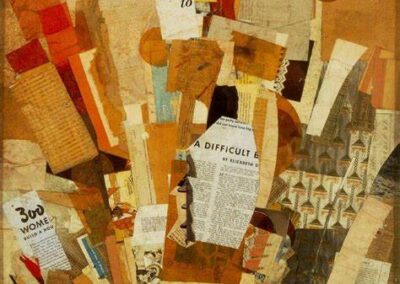

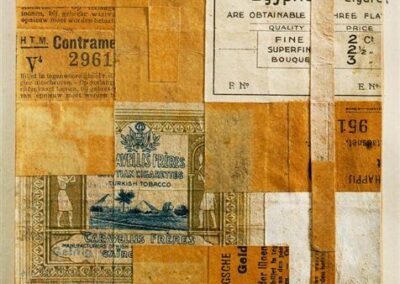

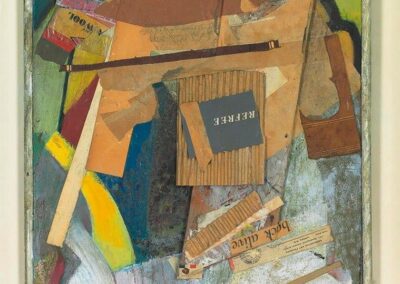

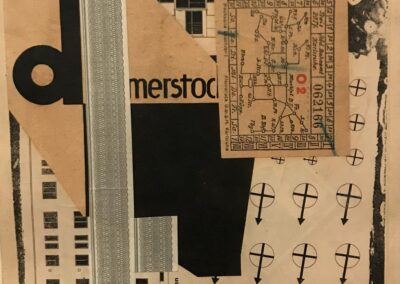

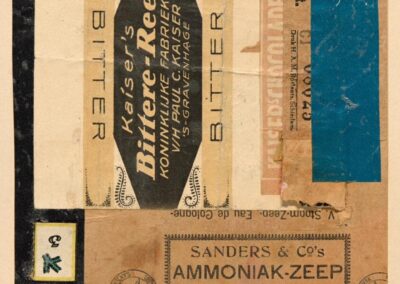

Kurt Hermann Eduard Karl Julius Schwitters was a German artist but he spent the latter part of his life in exile from his country due to the rise of fascism in Germany. The latter labelled him as a ‘degenerate artist’ alongside such other fine artists as Hannah Höch and George Groz. An artist who worked in a variety of media, Schwitters is best known for his collage and assemblage works which are still influential decades after his passing.

From Henie Onstad Kunstsenter : He “was one of the most innovative artists of the 20th Century. His creative diversity is evident in everything from collage, sound poetry, and architecture, to sculpture, painting, and typography.

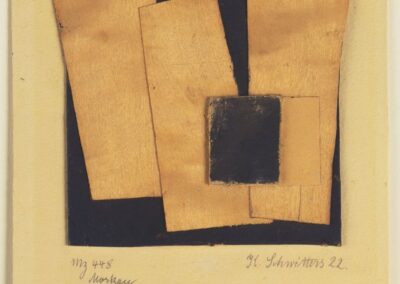

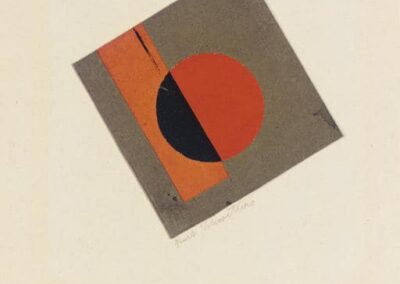

Although Schwitters is often associated with Expressionism and Dadaism, in 1919 he also created his own artistic movement —Merz. For Schwitters, “to merz” was to abolish boundaries: between artistic disciplines, between the meaningful and the banal, between art and life.”

Schwitters’ words : “Merz stands for freedom from all fetters, for the sake of artistic creation. Freedom is not lack of restraint, but the product of strict artistic discipline.”

He was born in Hanover, Germany, an only child : Schwitters had his first epileptic fit when he was 14, and this recurring condition was a factor in how the artist experienced the world and helped shaped his aesthetic. Never a particularly attentive student, Schwitters did study art at the Dresden Academy, with a focus on drawing, from 1909 to 1915. Passed over for military service in WW I due to his epilepsy, he was later conscripted as the war progressed. The majority of his military service was spent working as a technical draughtsman in a factory near Hanover : this also had a significant influence on his art and aesthetic. His words : “In the war [at the machine factory in Wulfen] I discovered my love for the wheel and recognized that machines are abstractions of the human spirit.”

Schwitters’ artwork began to take shape, in his own unique aesthetic, around 1918 : during his time at the Dresden Academy he had eschewed any of the contemporary art movements in Europe, but now the modernist avant-garde in Berlin became a touchpoint for the artist. The impact of WW I – specifically the tumultuous collapse in terms of economic and political spheres in Germany post WW I – helped push Schwitters towards the ideas espoused by the Dada movement.

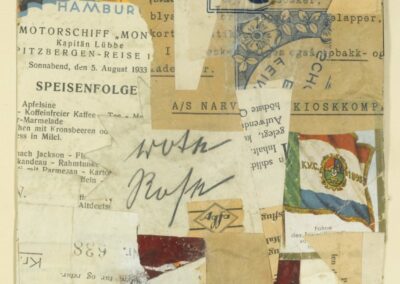

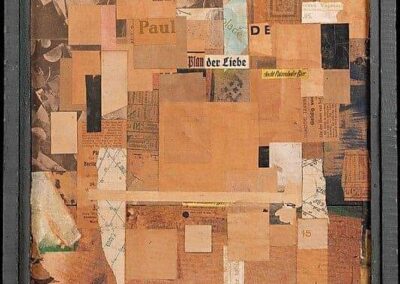

“During the war everything was in a state of ferment, the abilities and skills which I had brought with me from the academy were of no use whatsoever, and all around me people were fighting about stupid things which I myself couldn´t have cared less about…and then all of a sudden, the glorious revolution began. I don’t think much of such revolutions, for people must be ready for them. It’s like apples being shaken to the ground by the wind before they’ve time to ripen, such a shame. But it put an end to that enormous swindle which people call war. I quitted my job without notice and then things really got moving. The turmoil had only just begun. At last I felt free and I gave my jubilation in a loud outburst. Not being wasteful, I took everything with me that I could find, for we were now an impoverished country. One can also shout with junk – and this I did, nailing and gluing it together”

That same year (1918), Schwitters would mount a solo exhibition at the important Der Sturm gallery in Berlin: he also published An Anna Blume, a Dadaist poem which launched Schwitters to prominence among the German Dada movement, garnering the attention of people like Raoul Hausmann (who is associated with the aforementioned major artist Hannah Höch) and Hans Arp. Schwitters was now a major figure in the German Dada movement.

Although he was interested in some of the artworks being produced by Swiss Dada artists, Schwitters continued to develop his own unique style, specifically in terms of his use of collage with everyday objects and other social ephemera.

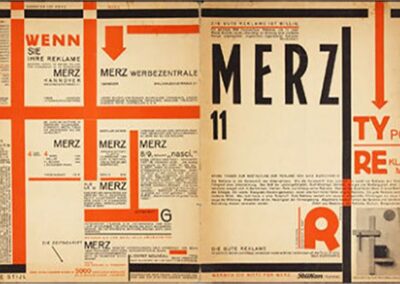

He began to produce Merz magazine in 1923 : in many ways, this was both the major ongoing accomplishment of his artistic career as well as acting as focal point – and platform – for many of his fellow artists, often within the sphere of Dada but beyond it, as well, as this was an exciting and eclectic time in European art, and especially Germany.

From The Art Story : “Avant-garde periodicals provided an excellent means of exchange for European artists, and through this publication Schwitters formed relationships with leading modernist thinkers such as Theo van Doesburg, Hannah Höch, Hans Arp, Tristan Tzara, and El Lissitzky. His relationship with the Dutch van Doesburg was especially close and in addition to exchanging content and advertising in their periodicals, the two frequently visited one another’s family homes. Tokens of the artist’s various friendships were integrated into the fabric of his home in an ever-growing Merzbau, a large sculptural installation worked on for fourteen long years that incorporated a collection of art and objects from these friends, combined into continually changing tableaux.”

Schwitters was also working in the field of commercial art, graphic design and typography at this time (and it can be seen that one often fed the other and his aesthetics mixed and merged). He often collaborated with Kate Steinetz – often referred to as the Mama of Dada – in producing children’s stories that were unique for their style and illustration.

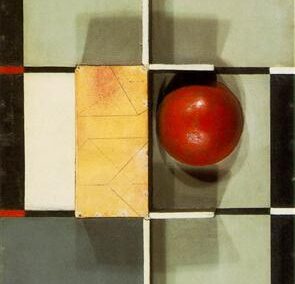

This work – as well as his continuing artistic works for Merz magazine and his more mainstream commercial endeavours – began to show more elements and influences from the Constructivist and De Stijl movements, focused upon balance, order, and line and less of the joyful, surrealist chaos of Dada that was his earlier aesthetic.

In 1937 Kurt Schwitters’ art was branded as “degenerate” by the nazis : like many important German artists targeted in this manner, he was now in danger of prison or being sent to the concentration camps. Schwitters emigrated to Norway that same year and when the nazis invaded Norway in 1940, he then fled to England.

Schwitters would pass away in 1948 from acute pulmonary edema and myocarditis – the day after he was notified that he had been given British citizenship.

Originally buried at St Mary’s Church, Ambleside (in the UK) : in 1966 a small stone marker with the text Kurt Schwitters – Creator of Merz was placed there, to mark his grave. This is still there, though his body was moved in 1970 to his native Hanover (at the Stadtfriedhof Engesohde) where he lays under a marble copy of Schwitters’ 1929 sculpture Die Herbstzeitlose.

“Art is a primordial concept, exalted as the godhead, inexplicable as life, indefinable and without purpose.”

Much more about Schwitters’ life and artwork can be seen here and here.