The next person of importance in this continuing series is Jack Henry Pollock (1930 – 1992). He was arguably the most influential figure in Toronto’s art scene during the 1960s and 1970s.

With the Artist You Need To Know series we’re not limiting ourselves to just featuring significant visual artists : we’ve often highlighted those who helped build and foster cultural communities, institutions and spaces. Jack Pollock is as important in this sphere as some of our past features that include Barry Lord, Alan Jarvis and Norman McLaren. These are individuals whose impact was to lay groundwork for others, and are as important in this way.

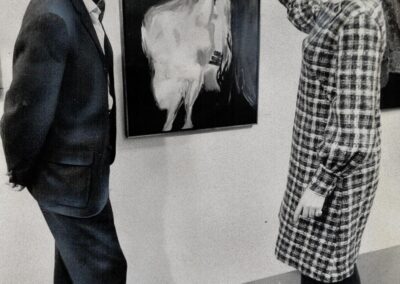

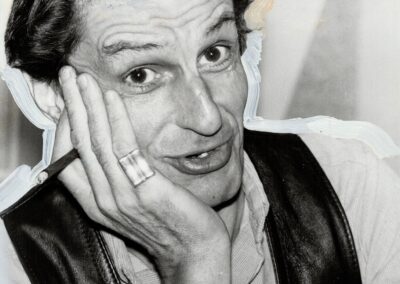

Pollock was a painter, art educator, author and gallerist who was not only a fixture on the Toronto art scene for over three decades but played a defining role there. Often described as ‘flamboyant’, he was the founder and owner of The Pollock Gallery which was open from 1960 until 1983 in various locations across the city of Toronto.

He ‘was widely reputed to have a skilled eye for identifying talent in young artists and was instrumental in the careers of many notable artists’ (from here). Amongst them were Ken Danby, Charles Pachter, Robert Bateman, Norval Morrisseau, Paul Founier, Tony Calzetta, Telford Fenton, Judy Singer, Ron Martin, Jack Bush, Abraham Anghik Ruben, and Jo Manning.

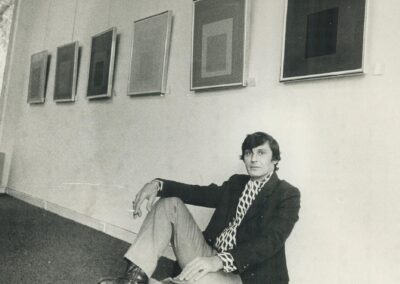

The Pollock Gallery also exhibited an impressive array of international artists, many of them for the first time in Canada, including Willem de Kooning, David Hockney, Josef Albers, Anni Albers, Claude Yvel, and Victor Vasarely.

In terms of Canadian art history, Pollock is most often spoken of in conjunction with Norval Morrisseau (arguably the most significant Indigenous artist of the last half century in Canada). This is both a positive thing and something that Pollock ruefully acknowledged (in 1984) would overshadow his many other important accomplishments : “I’m sure that, if I were to die tomorrow, the single most important thing people would remember me for is, damn it, the discovery of Norval Morrisseau. I’d like to think that I’ve done other equally important things. However, that’s the way it is.”

A graduate of OCAD University (when it was still OCA | Ontario College of Art) in 1954, Pollock would go on to study at the esteemed Slade School of Fine Art in London in the UK. On his return to Canada, he worked as a colour consultant for a paint company : this came to an end when Pollock suffered from mental health issues and was subsequently hospitalized. However, this experience – especially the art therapy that was essential to his recovery – was instrumental in his decision to open the Pollock Gallery.

Two years later he would meet Norval Morrisseau while teaching in Northern Ontario : the Ojibwa artist’s solo exhibition at the Pollock Gallery is considered both the launch of Morrisseau’s career but also one of the most important artistic events of the burgeoning Toronto – and Canadian art scene – at that time.

Pollock’s relationship with Morrisseau was tumultuous. A somewhat famous incident occurred when “in 1973, Pollock found himself accused of theft by Indian Affairs of Canada employee Bob Fox who was “managing” Morrisseau on the side while the artist was incarcerated. Morrisseau had instructed Pollock to take several paintings to Toronto to be sold; Fox accused Pollock of stealing the paintings. Pollock was found not guilty of the charge and in an unusual occurrence, he was complimented at length in the resulting judgement issued by the Court.” (from here)

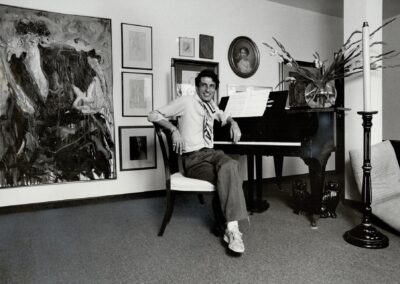

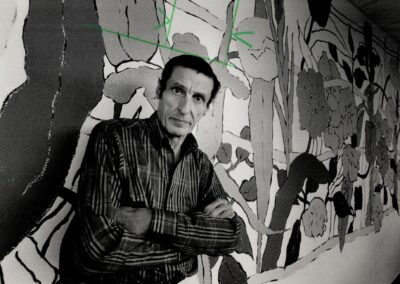

While working with a variety of artists – both Canadian and international – Pollock was continuing his own artistic practice, and his works can be found in a number of collections, including the National Gallery of Canada. Pollock’s style was often expressionistic, exploring abstraction, vivid in colour and tone, and depicted aspects of his life in a simple but evocative manner.

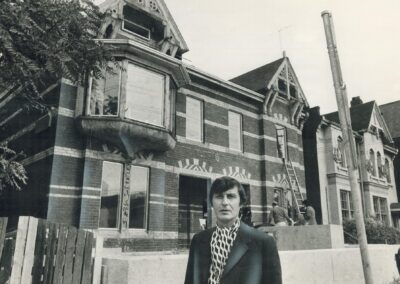

Although earning both success and a degree of ‘celebrity’ in the Canadian cultural scene, Pollock was quite honest about how ‘he was not business-minded. Pollock began having serious health and financial difficulties in the late 1970s. In 1976, after overseeing an expensive renovation for a large gallery space across the street from the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), he saw the AGO close for construction and his real estate venture turned sour. Under enormous financial pressure, he was admitted under psychiatric care to the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry. He recovered after 3 months and re-opened the Pollock Gallery on Scollard Street where, rather than declare bankruptcy as suggested by friends, he began to repay his debts.” (from here)

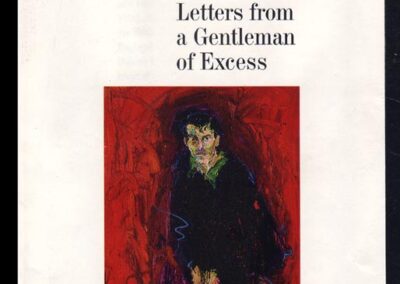

Pollock published, in 1979, with playwright, CBC broadcaster and polymath Lister Sinclair the notable book The Art of Norval Morrisseau. Two years later, Pollock would also publish a book of his poems, We All are All (and Other Thoughts on Days Alone). His most famous – and incisive and engaging – book Dear M: Letters from a Gentleman of Excess would be published in 1989, more of that later in this article.

In 1981, artist, animator and filmmaker Derek May produced the documentary Off the Wall in which Pollock was an important voice: “In this feature documentary, art and business collide with a look at how artists and artistic integrity achieve success in the marketplace. Sketches on artists and the art world are combined with exploration by the filmmaker of his own relationship to art.” This can be enjoyed here at the NFB (National Film Board of Canda) site.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Pollock’s financial difficulties and addiction issues began to take a major toll on his life and work : a variety of factors exacerbated this, including a decline in his relationship with Norval Morrisseau and the shifting economics of the commercial art world. The Pollock Gallery would close in December of 1981, and Pollock would be admitted to hospital in Toronto for heart surgery that same year.

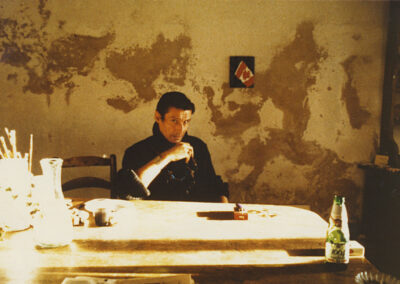

In 1984, Pollock – seeking respite from his depression, which had led to a self committal for psychiatric care – left Canada to live in Gordes, in Southern France. In many ways, this relocation – or perhaps isolation from the Toronto community that he had been defined by, and helped define – led to a renaissance in his artwork and writing : during this period he had many successful exhibitions in Gordes (September, 1984), Marseille (April, 1985) and Vichy (June, 1985). Pollock was painting daily, and produced several hundred works, while also writing back and forth to a psychiatrist in Toronto that would be the framework for his autobiography Dear M: Letters from a Gentleman of Excess. With his usual insightful criticality, Pollock observed about this correspondence : “What that poor bastard was letting himself in for when he said ‘Write me’!” “It all just poured out. I don’t think I could have made it without those letters.”

Published in 1989, Dear M (the edited letters) was shortlisted for the City of Toronto’s Book Awards a year later. It stands, decades later, as both a very honest memoir as well as a necessary social history to the times and world that Jack Pollock lived within. It was praised by both critics and readers.

One critic offered the following : “The letters are feverish outpourings from a man prone to extremes of behaviour followed by recriminations and self-doubt. Pollock is borderline obsessive about relationships, his own sexuality, and the psychology of living and putting the past into some sort of healthy perspective. What saves Pollock’s letters from preachiness are his vulnerability and almost guileless voice. In any case. Dear M has more dimensions than Pollock himself. The book is rife with anecdotes and pithy evaluations of artists.”

Pollock had returned to Toronto a year before the publication of his memoir : his medical problems with his heart were still an ongoing concern, and he further learned that he had HIV. He had never tried to disguise or hide his sexuality, and wrote frankly about being homosexual in all of his books. When Pollock was diagnosed with AIDS he became a vocal advocate for both research in this area and for those afflicted with the disease.

He has often been described as ‘defiant’ and the diagnosis did slow Pollock down, but he continued to paint and exhibit : “It didn’t seem fair that after I’d gotten my life together, I was hit by AIDS, so I decided to paint my rage. You can lash out on paper, violate it, and it just absorbs the anger. No one gets hurt.”

Jack Pollock died on December 10, 1992 : “I’ve been thinking of death a lot, and I am amazed by its inevitability, frightened, as we all are, of the totally unknown, and yet feel a long sleep is somehow earned by those of us who live on the edge.”

A short video from the AGO about Jack Pollock’s writings and ephemera in their collection can be seen here.